Entries, exits, permits 20 Oct 2:00 AM (yesterday, 2:00 am)

A reflection on traveling through the globalized walled city.

Doha had an eerie unnaturalness to it. Like existing in Jordan Peele’s Get Out. I had left the fake Venice of the Bellagio in Vegas only to find myself in a newer, faker, Venice in the Villagio in Doha.

The world exists in the same algorithm. I swear, there is the same coffee shop, in every corner of every city. Everything is just one giant “for you” page, ready to be scrolled.

At the airport in Doha, a woman tries to check in at the counter before me. She is dressed in a black flowing Abaya. The check in agent scans through her passport. After a few seconds he returns it back to her. “You do not have an exit permit from your sponsor.” He says. She stares blankly but knowingly at the agent, collects her passport back, and quietly moves to the side of the counter to give me access. Her face contains multitudes of emotions – a migrant worker caught in between, never completely staying, never completely leaving.

Las Vegas, United States

On this Friday I am wearing a blue jellabiya, and the Vegas wind swirls it around my body as I figure out directions to the mosque. A cab with a casino advert highlighted on its roof slows down in the middle of the street. A middle-aged man puts his head through the window and shouts towards me:

“Going to the mosque?”

This stranger gives me a five-minute lift to the mosque. Every minute or so, he slightly opens the door of the car mid-ride to spit some of the kolanut in his mouth, all this while ranting about Trump.

“He signs a paper and cancels everything. You know. Paper signed. He cancels me. Paper signs. He cancels you. Paper signs and everybody is sent away.” I do not say a word throughout the ride.

*

Another Friday, I walk on an almost empty campus when a red Toyota corolla that has been circling around the lot, speeds towards me with headlights fully on. A man winds down the side window and smiles at me.

“Yo! How do I get the fuck out of this school?”

LAX – Los Angeles International Airport

I am at the airport in LA on a phone call with Salma. There is a 9-hour time difference between our bodies, but the sound waves of our voices place our conversation in the same space. “You know, there are 7 million vending machines in the US” she casually mentions mid-sentence.

Now all I see are vending machines: a Kylie Jenner machine; a farmers healthy snacks machine, a 24 hours flower vending machine. Who will ever need to get a flower in the middle of the night?

When I sleep on the flight, there are vending machines haunting me in my dreams. I wake up, panting, connect to the in-flight Wi-Fi and google fun facts about vending machines.

Whenever in her lifetime Salma happens to visit Japan, I will call her and let her know once she lands in Tokyo: there is a vending machine for every 20 people in Japan! Ha!

Juba, South Sudan

On April 5, at the Juba airport in South Sudan, the United Stated deported a man in what became an international merry-go-round. South Sudan refused his entry, insisting that he is Congolese, and then deported him back to the United States. In response, Marco Rubio threw a tantrum and banned all visas of South Sudanese passports, plus sent this man again back to South Sudan. Because Africa is a country.

I have a printed picture of Makula Kintu pasted on my work desk. He is wearing a red t-shirt and a grey jacket on top of it. He has his fingers clasped together, his mouth agape, like a meme of astonishment.

For his first flight, he had been deported from the United States to South Sudan via Egypt Air, which means over the days he had been moved around from the US, through a connecting flight in Cairo, and then another flight from Cairo to Juba in South Sudan. For his second trip, from Juba, he would then have been returned through another intermediate country and then back to the United States where he would be denied entry at the border.

For a third trip, Makula Kintu was then again returned back, from the United States connecting through another country and again to Juba where he was finally kept under detention. Makula had first entered into the United States in 2003.

In all the news articles about Makula Kintu, he is not provided a voice by the press. Airport officials, foreign secretaries; custom and border agents speak for him. This is the only picture of him used in all the press filings – mouth agape and confused. In all of those flight miles he collected over days, no journalist asked Makula Kintu even if it is just for his opinion on how terrible the in-flight meals can be.

*

On different coordinates, on different maps, stories repeat. Cities absorb other cities, vending machines multiply like viruses. Humans are trapped in bureaucratic loops. The world is a continuous scroll: how do we get out? How do we make the algorithm stop repeating itself? In every existence, there are black bodies bearing witness.

Zoë Wicomb’s local universalisms 20 Oct 12:00 AM (yesterday, 12:00 am)

The passing of the pioneering South African writer and critic leaves behind a body of work that challenged racial mythologies, unsettled identity politics, and grounded transhistorical vision in the particulars of place.

Zoë Wicomb’s passing, on October 13 at the age of 76, has prompted an outpouring of tributes from black women writers and scholars across the globe, a reflection of the immense political and literary impact of her work. Figures like Pumla Gqola and Gabeba Baderoon have highlighted her fearless critique of colonial and racial mythologies, her insistence on complexity, and her refusal to be co-opted by easy solidarities. These tributes speak to Wicomb’s lifelong commitment to unraveling the social fictions that continue to shape South African life: fictions of race, gender, belonging, memory, and power. As a writer, critic, and teacher, she challenged her readers not with loud declarations, but with careful, unsettling questions.

Her 1992 reading of Bessie Head’s Maru is an early marker of this political vision, as is her seminal 1998 essay on shame in the South African literary imagination. There, Wicomb showed how the category “colouredness” had been shaped by a history of symbolic associations—tainted bloodlines, racial impurity, miscegenation—and how these myths, far from being neutral descriptors, continued to saturate post-apartheid discourse. Yet her analysis was often misread. Some critics mistook her deconstruction of these colonial fictions as a tacit endorsement of them, folding her into the very discursive lineage—figures like Olive Schreiner or Sarah Gertrude Millin—that she so precisely challenged. This kind of misreading was not unfamiliar to Wicomb. In fact, her work bears a certain affinity with that of J.M. Coetzee: both writers have at times been accused of “naturalizing” racial discourses when, in fact, they were intimately deconstructing them.

Another important way in which Wicomb contributed to South African political debate is through her sustained engagement with the figure of Sara Baartman. Baartman—an elusive but recurring presence in her novel David’s Story—looms large across Wicomb’s oeuvre as an index of historical memory. Yet unlike many South African, North American, and Black diasporic poets, playwrights, and novelists who have sought to convey definitive “truths” about Baartman, Wicomb turns her gaze instead to the politics of re-membering itself. What demands interrogation, she insists, is not Baartman’s historical “truth,” but the ways she is made to serve the symbolic needs of the present—the ways she is repeatedly projected upon, claimed, and conscripted to suit others’ purposes.

This point is made forcefully in her interview in the 2021 collection Surfacing, where she critiques certain currents of “woke” politics, particularly those associated with what she calls “bright young things.” In their eagerness to “speak truth to power,” Wicomb suggests, these voices can end up hardening complex truths, collapsing the contradictions of the past into performances of moral clarity that often reflect the psycho-political needs of the present more than the realities of history.

It is, in fact, deeply ironic for us to acknowledge—as we write this piece—that we, too, are implicated in this dynamic. Already, there are those who seek to claim and contain “Zoe” as a fully knowable figure (in the same way that many have already claimed, owned, and distorted Sara Baartman), ready to be remembered and reified. In this respect, our act of tribute risks echoing the very gestures Wicomb so often questioned the drive to fix, possess, and project an authoritative version of a life that resists such closure.

The political commitments described above were essential to Wicomb’s writing, her teaching, and her public commentary. All were shaped by the Black Consciousness politics that also nourished the vision of her contemporary, Jakes Gerwel, the celebrated rector of the University of the Western Cape, her alma mater, and the university at which she taught for many years. Wicomb boldly and consistently defended the strategic essentialism of “Biko blackness” in the mid-1990s, at a time when coloured separatism (and ethnic consciousness more generally) had begun to surface with virulent force. She challenged students at UWC, UCT, and Stellenbosch, as well as the broader public, condemning forms of identity politics that produced new essentialisms, exclusions, and at times, outright xenophobia. Like another of her contemporaries, Njabulo Ndebele, she stressed how these patterns found their origins in the very colonial and racist biopolitics they claimed to oppose.

Still, the scope of Wicomb’s vision, despite its deep-rootedness in South Africa and the local, was also astoundingly broad. Some may wonder why she focused so insistently on South Africa while living in Glasgow, Scotland, when a global and transhistorical perspective—so evident in her latest novel Still Life—was always available to her. But like Bessie Head, a South African writer she deeply admired, Wicomb chose to ground her expansive, universalist vision in the particulars of place: a view of the local that was at once compassionate and sharply critical. And like Head, Wicomb’s universality was never of the abstract, liberal-humanist kind; it was transhistorical and embedded, political and aesthetic at once. Still Life and October are both testaments to this. So too is the eclecticism of her critical writing, where canonical thinkers like Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, and JM Coetzee appear alongside marginalized knowledge-makers—lesser-known Black South African women writers, or “dated” critics like Lewis Nkosi—without hierarchy or defensiveness.

Wicomb’s “local” was a South Africa she knew intimately—at least in the 1990s and early 2000s—and which she wrote about with respect, love, and also with a passionate outrage at the injustices that endured. Her local was also the realm of sharp social commentary: she wrote about colorism among those classified as African and Coloured, about the anxieties of Black women around hair texture in a world still governed by white-centric beauty standards. And her writing was lyrical too, often poetic: evoking the striking landscapes and flora of Namaqualand, where she was born (as in October), or capturing the speech patterns and idioms of people of color from the Northern Cape and the streets and mountains of the Western Cape.

For us, she’s been a wonderful friend: inspiring, hilariously funny, outrageously adventurous, and incredibly generous. But she’s also been a pioneering South African writer of novels, social commentary, and literary and cultural criticism. A great loss to many is that she did not live long enough to write even more.

As spring returns and the Namaqualand flowers bloom—just as they do in October, the novel that bears the season’s name—we are reminded of her deep feeling for place and its quiet rebellions. In that novel, one of Wicomb’s more complex, though minor, characters, Sylvie, reflects on the patch of land she has shaped into her own:

Here…where she has planted the vygie…she has always known is for her, Sylvie, and her alone. That is why she turned the patch into a garden, arranged the stones…In the veld she dug up kanniedood and koekemakranka, and planted them around to show up the glorious purple. … If, as AntieMa says, the devil has blown in her blood, then that blood is the screaming purple here at her feet…

It is hard not to read this as a kind of quiet credo, one that speaks to Wicomb’s sensibility as a writer who tended her literary and political garden with fierce attention, irony, and love. The screaming purple at our feet is hers, too.

Reading List: Brooks Marmon 17 Oct 4:00 AM (3 days ago)

The writings of Edson Sithole, Zimbabwe’s forgotten nationalist thinker, reveal both the promise and perils of pan-African politics in the independence era.

For prominent Zimbabwean legal minds seeking to dismantle white domination in their homeland, 1975 was a trying year. The renegade British colony’s first black lawyer, Herbert Chitepo, who led the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) from exile, was killed in a car bomb in Lusaka in March. In October, ZANU’s former publicity secretary, Edson Sithole, one of the most prominent nationalists who had not gone abroad, disappeared after leaving a well-known hotel in downtown Harare (then Salisbury).

Sithole, a self-made legal scholar with a Doctor of Law degree from the University of South Africa, was born in rural Southern Rhodesia to illiterate parents in 1935. Regrettably, his political thought and actual contributions to Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle have been subsumed by the unexplained nature of his demise (agents reporting to Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith were believed to be responsible).

A forthcoming book I’ve compiled for the Voices of Liberation series of South Africa’s HSRC Press serves up a political biography of Sithole (written by me), accompanied by the full reproduction of some two dozen writings and speeches by Sithole from the late 1950s until days before his elimination. Tinashe Mushakavanhu’s contribution to this series on ZANU’s founding leader, Ndabaningi Sithole (a distant relative), crystallized the idea for this manuscript.

As a PhD student researching the politics of decolonization in colonial Zimbabwe in the 1950s and 1960s, I was acutely aware of the standard historiographical lament: that the continent’s independence-era stalwarts left behind a limited archive. Although the personal papers of their white settler counterparts are disproportionately preserved, the example of figures such as Sithole leads me to believe that this claim is overstated.

As the Voices of Liberation and AIAC’s own Revolutionary Papers series demonstrate, a significant cohort of pan-African, anti-colonial nationalists embraced the power of the pen to assail colonialism.

During my doctoral studies, a thorough review of the African Daily News, a newspaper targeting a predominantly black readership, revealed that Sithole frequently contributed op-eds on political developments not only in Rhodesia, but across the continent. Like many similar periodicals, it has not been digitized. Thus, not only are his words out of circulation, but the research to recover them is a painstaking process. These essays form the bulk of Sithole’s voice in the forthcoming book.

Sithole was among a coterie of young turks contributing a stream of opinion pieces in this paper that have gone underacknowledged in the historiography. However, I was particularly drawn to his voice. A notable strand of my thesis, Pan-Africanism Versus Partnership (now published in book form), argued that the era’s emphasis on pan-Africanism sowed the seeds of authoritarianism, promoting absolute unity at almost any cost.

Sithole stood out as an exception. In 1961, Zimbabwe’s nationalist movement, under the direction of Joshua Nkomo, initially agreed to British-mediated constitutional reforms that preserved minority white rule. In African Daily News think pieces, such as “Nkomo was Tricked by Britain, but We Cannot Accept Clumsy Explanations to the People,” Sithole went against the dominant tenor of the struggle to denounce Nkomo’s prevarications.

Initially a rather solitary voice, Sithole’s condemnations of Nkomo gathered momentum, leading Ndabaningi Sithole to oversee the launch of ZANU, which provided a viable challenge against Nkomo. Sithole celebrated that development in a 1963 op-ed entitled, “Nkomo’s Sun is Setting.”

Sithole also critiqued African statesmen who he felt betrayed the nationalist cause. Nigerian Prime Minister, Abubakara Tafawa Balewa, who flirted with the white settlers of Southern Africa more than has generally been acknowledged, was another target. Sithole’s “The Role of Nigeria in Africa’s Struggle” displays an impressive knowledge of Nigerian domestic politics in a pre-digital age and a courageous willingness to call out the leader of one of Africa’s most powerful states.

When Ian Smith came to power in 1964, white rule in Rhodesia became even more repressive. Sithole was jailed, his party (ZANU) was outlawed, and the African Daily News was banned. References to African nationalist politicians in the local press became verboten.

In the early 1970s, Sithole emerged from several years of imprisonment to become the publicity secretary of another liberation movement, the African National Council. With his law practice thriving and party duties consuming much of his time, his for-attribution writings decreased.

However, an assortment of interviews and other materials, complimented by the emergence of an ANC-aligned newspaper in 1975, The National Observer, ensures that Sithole’s voice can be tracked into the 1970s. The Observer, a poorly preserved periodical, published what was likely Sithole’s last opinion piece, “How We Formed the ANC,” just four days before his disappearance. It continued his long-running criticisms of Nkomo and countered his nemesis’s framing of the liberation struggle’s trajectory.

Still, I felt like something was missing to tie together the various elements of Sithole’s discourse. In taking a leadership role in the ANC, seen as a more conciliatory party due to the presence of comparatively restrained intellectual voices and ecumenical figures in its leadership, Sithole appeared to have backtracked on his prior revolutionary zeal. Then, on a trip to the UK National Archives, I found the transcript of a 1973 address by Sithole, “Where Now, Rhodesia?”

The remarks were delivered to the Rhodesia National Affairs Association, a white dominated civil affairs society, just as the armed struggle heated up. They indicate a pragmatic attempt to avert the explosion of bloodshed that marked the second half of the decade in Rhodesia. That tumult cost Sithole his life, and its legacy continues to plague Zimbabwe today.

I hope that this recovery of Sithole’s political thought not only recognizes his intellectual role in African independence struggles, but also illuminates the repercussions of intransigence by powerful elites who seek to maintain their dominance.

Edson Sithole: Law, Liberation and the Cost of Dissent (2025), edited by Brooks Marmon, is forthcoming on HSRC Press.

Repoliticizing a generation 16 Oct 4:00 AM (4 days ago)

Thirty-eight years after Thomas Sankara’s assassination, the struggle for justice and self-determination endures—from stalled archives and unfulfilled verdicts to new calls for pan-African renewal and a 21st-century anti-imperialist front.

Yesterday marked the 38th anniversary of the assassination of Thomas Sankara, who, on October 15, 1987, was killed alongside twelve of his comrades during a coup led by Blaise Compaoré. Sankara’s brief but transformative presidency (1983–1987) reoriented Burkina Faso’s political economy toward self-reliance, gender equality, ecological stewardship, and non-alignment in global affairs.

For more than three decades, Aziz Salmone Fall, a pan-African activist, political scientist, and coordinator of the International Campaign Justice for Sankara (ICJS), has worked with Sankara’s family, Burkinabè activists, and international allies to demand truth and accountability. The long struggle has yielded historic breakthroughs: Compaoré, his former chief of staff, Gilbert Diendéré, and former Burkinabè army captain, Hyacinthe Kafando, were convicted of complicity in murder by a military court in Ouagadougou in April 2022. Significant questions remain regarding the enforcement of the verdict (each was sentenced to life imprisonment), the release of the French archives, and the larger fight against impunity.

In this conversation between Amber Murrey and Aziz Fall, Fall reflects on the enduring significance of Sankara’s revolutionary ideas and the ongoing movement for justice. They explore how the campaign navigates legal and diplomatic obstacles; how new regional dynamics such as Senegal’s political shift to the creation of the Alliance of Sahel States, shape ongoing political and economic struggles; and how a generation of African youth is being reinvigorated by Sankara’s vision of a sovereign, ecologically attuned, and socially just future.

Aziz envisions a renewed pan-African and anti-imperialist front grounded in what he calls the “Great South:” a collective of emancipatory forces reclaiming political and epistemic agency from the global periphery. Through his concepts of transinternationalism and a revived “Bandung 2” internationalism, he calls for a 21st-century alliance that transcends the nation-state, uniting peoples of the South and North in a shared struggle against imperialism and capitalist domination.

- Amber Murrey

The campaign you coordinate has long demanded justice for the assassination of Thomas Sankara. What were some of the lessons you learned over these three decades of organization?

- Aziz Salmone Fall

Thank you, Amber, for this opportunity to reflect at this important historical moment. The first lesson is that when we organize ourselves with self-sacrifice, courage, and audacity, anything is possible. In the summer of 1997, a few months before the [administration’s claimed] 10-year statute of limitations expired, Sankara’s widow, Mariam Serme Sankara, courageously filed a complaint against X for forgery. Our lawyers Dieudonné Nkounkou from Montpellier and Bénéwendé Sankara from Ouaga took up the case and assumed her defense. GRILA launched the ICJS international campaign Justice for Sankara in the form of an appeal against impunity. The appeal was endorsed by several organizations and prominent figures. I had the honor of coordinating this group of some 20 lawyers and, over the course of these decades, exhausting all remedies before the Burkinabè courts, which were manipulated within la Françafrique, and we appealed to the United Nations Human Rights Committee and obtained an international precedent against impunity in 2006.

Relentless campaigns to raise awareness of Sankarism and Pan-Africanism have borne fruit. Young people have taken up the cause. With the overthrow of the Compaoré regime, a new administration has allowed a new trial to be organized. It opened on October 11, 2021, and has resulted in the conviction of those who murdered Sankara and his comrades.

The second lesson is that some consider this to be a Pyrrhic victory. I have a great moral responsibility in this matter and am uncomfortable with its outcome. Most of the families who agreed to allow me to exhume the bodies were disappointed to see that there was insufficient DNA evidence to identify them. It must be said that the previous regime had not protected the Sankara site, where liquids had been poured over his grave in an act of desecration. The state preferred to use laboratories of its own choosing rather than those we had recommended. And when it came to reburying the bodies, the Sankarist supporters were divided between those who (along with the majority of the families) believed that they should not be buried at the Council of Entente where they had been slaughtered, and those who, supported by the current regime, and other Sankarist supporters, believed that a memorial should be erected there: the Sankara Memorial. It was recently inaugurated and is now their final resting place. In order not to embarrass the families, I declined the state’s invitation to the inauguration and the medal that was to be awarded to me. I had proposed a vacant space between the Cuban Embassy and the Council of Entente as a compromise, but this proposal was not accepted.

The third lesson is that despite our struggles, the culture of impunity can persist. The chief orchestrator is still protected by Françafrique, which refuses to die, and the current authorities—who claim to be Sankarists—have yet to request his extradition.

- Amber Murrey

Where do we stand today in terms of accountability and impunity, particularly concerning the conviction in absentia of Blaise Compaoré? What concrete steps will be taken next to ensure that the verdict is enforced?

- Aziz Salmone Fall

It may be surprising that a person who has committed so many atrocities, who has murdered his close comrades and many other opponents, whose henchmen have threatened us with death, who enriched himself by plundering the sub-region and who, moreover, contributed to introducing terrorism there, can enjoy, in complete tranquillity, the nationality of Côte d’Ivoire, a country he helped to destabilise, and live there in luxury. We take this opportunity to reiterate our request to Burkina Faso to demand his extradition, to Côte d’Ivoire to respect the deserved sentence he has received, and to France to stop supporting him. Perhaps the current regime in Burkina Faso fears Compaoré’s capacity for harm if he were imprisoned in Ouagadougou, but that is just speculation on our part. For our part, while once again congratulating our courageous lawyers, this part of the trial has been resolved, and we have achieved our objective of ensuring that justice is heard, something that had been denied us for so many years. At the level of international law, following the deaths of human rights experts [Louis] Joinet and [Doudou] Guissé, and despite their courageous efforts, we still do not have a binding convention on impunity.

- Amber Murrey

Access to national and international archives is vital to establishing historical truth. What progress has been made in releasing key documents from France or other countries? What strategies are being used to overcome political and diplomatic obstacles to full declassification? Is your sense that the thin portfolio of archives released by the French during the trial is the end of that process?

- Aziz Salmone Fall

We have spent decades requesting the declassification of secret and strategic documents. France has disclosed a batch of strategic documents, but these do not incriminate it. A third batch that was to be provided has been blocked by the French authorities. The rogatory commission that was to work on opening the international aspect of the trial, which was separated by the Burkina authorities, appears to still not have been set up [as of 2025]. There is a clear lack of willingness on both sides to finalize the resolution of this case. Our lawyers have unsuccessfully tried to get the authorities to take action. It is true that the situation of terrorist insecurity in the country and the region does not help matters. My reading of the documents and my assumptions clearly point to international sponsors, mainly French and American, and a few regional second-tier players.

- Amber Murrey

The recent political changes in Senegal have generated hope, including the appointment of Ousmane Sonko as prime minister and the plans to phase out the presence of French military forces. How do you assess the prospects for progressive change under the new government, and what role could Senegal play in supporting justice initiatives, such as the campaign for justice for Sankara?

- Aziz Salmone Fall

I have already had the pleasure of seeing the current prime minister give an interview at the beginning of his term, with a large poster of Sankara in the background, and he even attended the recent inauguration of the Sankara memorial. These are strong political signals. However, we did not receive any support or show of solidarity from his party during our campaign. It must be said that one of the characteristics of the AES and Senegalese regimes is that they are distinguished by their declarative and sometimes even active sovereignty, but they do not associate with revolutionaries. This may be a tactic in the face of imperialism, which is indeed powerful against young and fragile regimes. For the moment, we have a polite and distant relationship with all these regimes, which are not unaware of our pan-African sacrifices and struggles, which they themselves claim to support. In the case of Senegal, I proposed the pan-African platform Seen Égal-e Seen Égalité, a progressive, feminist, and ecological self-reliant social project. Seven parties have endorsed it and six candidates have chosen to draw on elements of it for their programs.

The regime has not endorsed it, but there is a certain influence, and it espouses an anti-neocolonial and anti-imperialist rhetoric. In practice, however, there will be no anti-capitalist break, but rather a pragmatic liberal management of the crisis, which we hope will be more patriotic than that of the former regime. But if there is already patriotic management of public funds and the settlement of impunity for financial and bloody crimes, that would already be a lot. We believe in a gradual break and will therefore continue in this vein, as we see no other options for Africa.

- Amber Murrey

Young people across the Sahel and wider Africa are increasingly politically active in digital spaces and online communities. How does the Justice for Sankara Movement inspire and connect with this new generation to build pan-African alternatives to both external domination and authoritarian statecraft, for example, in Cameroon, Chad, and elsewhere?

- Aziz Salmone Fall

We are convinced that our struggle against apartheid and for national liberation, followed by three decades of fighting against impunity and promoting Sankarism and Pan-Africanism, have helped to shape thousands of young people and generations of conscious Africans. At the same time, this politicisation is often superficial, as young people globally have been affected by three decades of depoliticisation caused by neoliberalism and the divestment of the state. I believe that those who have accompanied us in this struggle against autocracies, foreign bases, or pan-African development, and who have even supported it, are different from others in their pan-African consciousness. But it is a long and difficult struggle against a hostile world order and stubborn and perverse autocracies that have contributed to perpetuating ignorance, obscurantism, and all kinds of diversions to distract young people from their historical responsibility for transformation. But the contradictions and demands of life and survival are leading these young people to discover our struggles, which are identical to theirs, and the ancestors of the future, from Cabral to Ben Barka, from Lumumba to Fanon, who illuminate our struggles.

- Amber Murrey

The formation of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) by Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger marks a shift in Sahel geopolitics and autonomy. From the standpoint of the region’s peoples and movements, what are the most exciting aspects of recent moves?

- Aziz Salmone Fall

Undoubtedly, greater collective self-esteem. The simple fact that African countries are uniting in the face of adversity is progress. The fact that these are military juntas does not seem problematic to me; Sankara and his comrades were indeed soldiers with a certain social conscience. The sovereigntist stance and determination to fight the terrorist hydra, even if it means abandoning historical external support and favoring others, cannot be achieved at the expense of democracy or regional and pan-African dynamics. We need an open stance toward all peoples and all their components, and not just the military, which does not have a monopoly on politics. We must be confident and not suspicious. We must stand up against the tide of autocracy on the continent. In Tunisia, my comrade Khayam Turki has been accused of conspiracy and sentenced to two decades in prison with complete impunity; in Benin, my comrade Lehady Soglo is still convicted and in exile on unclear charges; our comrade Gbagbo in Côte d’Ivoire was previously rendered ineligible for major elections [this ineligibility was lifted in 2023]; Maurice Kamto in Cameroon has also been brutally sidelined [in the 12 October 2025 presidential elections]… Libya, Congo, and Sudan are being carved up and preyed upon by profiteers, bandits, extractive industries, and more. These circumstances do not allow for the clarity and serenity needed to build Pan-Africanism. For example, the AES is falling out with Algeria and paradoxically turning to Morocco. What about the Sahara issue, or other West African trade routes? Our leaders must learn to disconnect to ensure better accumulation, consult each other more strategically, let our peoples flourish, and not adorn themselves with medals, honours and enrichment; and concern themselves with questioning the old model of development by opting for a balance in symbiosis with nature that satisfies the essential needs of those who are deprived, proposing strategies for full employment, redressing inequalities, particularly concerning the status of women, and educating for progressive knowledge… these are some of the signs we are waiting for in concrete terms.

- Amber Murrey

As you know, this month marks the 38th anniversary of the assassination of Sankara. In his 1987 address to the OAU, Thomas Sankara warned that “He who feeds you, controls you,” and elsewhere cautioned that, “It is natural to fear to be outside the norm, but the courage to refuse conformity is the beginning of freedom.” In your view, what concrete forms of economic or diplomatic refusal allow African countries to assert autonomy, sovereignty, and justice in today’s international world order, with nested global racial hierarchies, and capitalist expansion?

- Aziz Salmone Fall

Everywhere, the struggle to preserve equality or to increase inequality continues. The balance of power is political and, depending on the worldview and the period, gives rise to increasingly sophisticated superstructures to resolve issues of wealth, power, and meaning. The resulting institutions can be immutable for a long time, or they can be brutally overturned, creating new relationships of power and knowledge.

It is up to us, in this exceptional historic moment of redeployment of imperialism in the 21st century, to help complete the efforts of so many people, like Sankara, who have fought for our freedoms and our development. In the current state of disarray and expectation, and without nostalgia, a lucid response from the organic forces of the Great South is inexorably becoming aware of its anti-systemic potential. This presupposes recovering the state’s room for manoeuvre, rediscovering the organizing potential of peoples and the coherence of the convergence of transversal struggles beyond sovereignty against transnationals, war, and the rapacity of the market, and in defense of the equal status of women and the protection of the common good and the environment. This is not a time for nostalgia and mere commemoration, but for understanding that the non-aligned must now have the courage to align themselves against imperialism and reinvent a transinternationalism of peoples. If the latter accepts the leadership of BRICS, the industrial champions of the Great South, it rejects their sub-imperialist temptations and reaches out to the peoples of the core countries to fight barbarism.

I propose transinternationalism starting from the Great South first, so that once it has crystallised, and without sub-imperialism, it can irradiate the peoples of the North whose interests are not so opposed to ours, confronted as they are with the rigours of their uniformising economic, cultural, educational, and political standards and systems. Universality will only exist when other homeomorphic and endogenous equivalents have irrigated it, and when hegemony fades through fertile and reciprocal acculturation.

The Great South must take back the epistemic initiative and restore the sense to participate in the uninhibited construction and non-Eurocentric reconstitution of knowledge. All the peoples and nations that have suffered colonization and continue to suffer its after-effects must learn to work together to emerge from their condition. Whether through South-South cooperation at all levels, bilateral, multilateral, or simply as citizens.

We need to deconstruct the Eurocentrism embedded in our cognitive frames that are deeply enmeshed in our thoughts and practices of knowledges. By transnational, I mean the extra-state and national dimension, both infra- and supra-national, which incorporates progressive internationalisms, mainly those of workers and the jobless, ecologists and feminists. So we’re going beyond the first internationalism and adapting it to the 21st century, to its equivalents in different parts of the world, in order to achieve real universalism. Transinternationalism makes it possible to incorporate internationalism, which itself went beyond the national question by advocating workers’ solidarity, transcending it to deploy politically, socio-culturally, and psychologically a progressive rearguard and vanguard front of organic forces to meet the challenges of the 21st century and beyond.

We need to build a collective internationalist network of resistance to imperialism, starting by strengthening its axis in the most promising parts of its periphery. There is an urgent need for a political level, which exists only sporadically on an event-driven basis. This organized and diverse nebula must bring together, based on Bandung 2 internationalism, the fronts, parties, movements, and individuals likely to propose to the peoples, the alter-globalist network, as well as to the social formations and productive or unemployed forces of the world, an alternative project to capitalism. A project against the modernization of pauperization and technocratic depoliticization, a free, egalitarian, democratic, feminist, and solidarity-based project for the construction of a responsible universalist order without oppression for humans and nature alike. This must be done in a respectful, democratic, and united way, in the diversity of our obedience(s), with the prospect of rebuilding a world labor front conscious of the issue of the commons, the last non-commodified public spaces, and the importance of adopting a universal declaration for the common good of humanity.

The challenge of an anti-systemic response based on the spirit of Bandung should consider the feminist, ecological, and progressive challenge at the heart of any analysis aimed at democratically re-politicizing peoples with a view to an upsurge in the defense of peace, of the commons and an alternative to capitalism. The democratic re-politicization of our popular masses on the basis of dynamic balance and a stand against the militarization of the world requires the re-foundation of a tricontinental front to counter the military impetus of collective imperialism and move toward the equivalent of a 5th International. At the very least, it is important to recall the eight principles we set out in 2006, during the World Social Forum in the Bamako Appeal.

- Amber Murrey

Thank you so much for your time.

- Aziz Salmone Fall

The king of Kinshasa 15 Oct 3:00 AM (5 days ago)

Across five decades, Chéri Samba has chronicled the politics and poetry of everyday Congolese life, insisting that art belongs to the people who live it.

Chéri Samba is the undisputed king of popular painting from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Over the last 45 years or so he has been depicting the everyday concerns of his countrymen and women, reflecting on everything from education, morality, sexuality, and corruption in his paintings, using himself as a subject to comment on the social and political realities in his country. These scenes are depicted in his trademark style of humor, in vivid color, and often accompanied with text in his native Lingala or French.

Born in 1956, Samba’s artworks first came to international attention in the 1989 exhibition Magiciens de la terre (Magicians of the Earth) at the Centre Pompidou and the Grande Halle de la Villette in Paris. Since then, his artworks have been exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston; the National Museum of African Art in Washington, DC; the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao; the Tate Modern in London; the Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art in Paris; the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris; the Museum of Modern Art in New York; the Venice Biennale; Documenta; and other places. Riason Naidoo met up with Chéri Samba in Paris in 2020 at galerie Magnin-A in Paris.

- Riason Naidoo

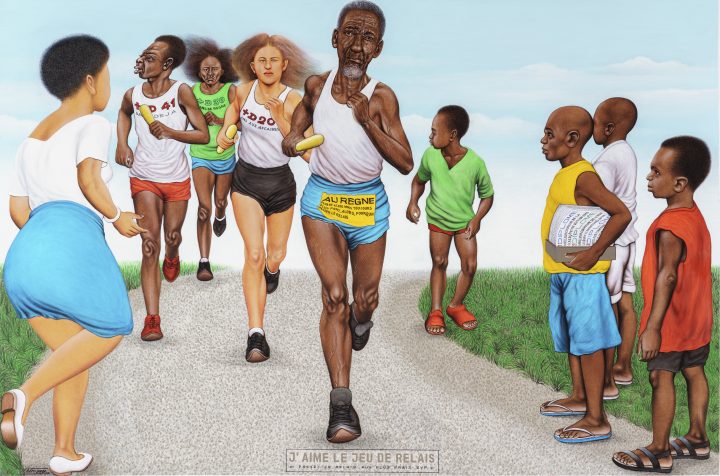

This painting is fun, J’aime le jeu de relais (I Like the Relay Game), 2018.

- Chéri Samba

The relay game, yes. I like it because you don’t want old people to spend all the time in the positions they hold. They would still have to have the spirit of wanting to leave room for young people too. If we have to appropriate places from young people all the time, why then do young people study? Why have children if we do not allow time for them to move on in life as well? That’s why I like the relay game. Let children take the place that adults have previously occupied.

J’aime le jeu de relais, 2018. (I like the relay game) © Florian Kleinefenn. - Riason Naidoo

You say you were born an artist. Can you expand on that?

- Chéri Samba

When you come into the world, you don’t choose what you should be; it’s like, in a curious way, doing a job you didn’t choose. When I was a child, I saw myself drawing something in the sand; like everyone else, every child needs to play, to play in other skies. I had no materials. I used my fingers to scribble something in the sand, and little by little when I was in school I started to have some white paper with the ballpoint pens. With pencils, I was making drawings. I copied comics from the entertainment magazines that were all the rage at home in Kinshasa. I would keep them in notebooks; it was my hobby. My fellow students bought it. That’s why I said later I was born an artist. I didn’t choose it, it just happened.

- Riason Naidoo

You’ve been in Kinshasa ever since you moved there from your village as a young man. What is so special about Kinshasa?

- Chéri Samba

Kinshasa is the city to which I am drawn, but I was born in Kinto M’Vuila in lower Congo eighty kilometres from Kinshasa. We do not choose the place of birth. After dropping out of school, I preferred to go to Kinshasa because almost everyone wanted to live in the capital of the Congo. It is a desire. I changed my studio recently [after many years] from the corner of Avenues Birmanie and Cassa Boubou to 250 Avenue Commerciale, and that is where I am, until now.

Souvenir d’enfance, 2020. (Childhood memory) © Florian Kleinefenn. - Riason Naidoo

Who were the artists that inspired you in then Zaire?

- Chéri Samba

Frankly, I didn’t have a role model. At the beginning, it was as if I existed all alone in the world. It was just after several years [of being an artist] that I heard about others. I thought I had to try to see what these artists were about. We got together, we rubbed shoulders, but I wanted to be true to myself. As we are at the show of three artists [now in Paris], the other two being Bodys Isek Kingelez and Moké; they were my colleagues, my friends. They came on stage before me, and I appreciated their work. I met them; they accepted me. Each one was different.

- Riason Naidoo

What makes your work different from theirs?

- Chéri Samba

Isek Kingelez, he was a model maker, so that was a big difference between painting and models; Moké, a painter. We can see very well that the processing of my images is not the same. I preferred to do a little realism … even if it could have a little flaw. There is another difference: I wanted to put some text in my paintings, because before I set out on this adventure, I didn’t believe it. I couldn’t see a painting that bore text, and I almost suffered for it.

The people from the Academy of Fine Arts [in Kinshasa], the teachers from that school (who wanted to take care of my work, while I was not their student) said, “But how can this artist afford to put texts, to write on his paintings? Maybe he doesn’t know how to make his images understood.” I said, “Let me do what I want to do.” My desire is to hold the attention of people in front of my work so that they take time to contemplate my work. There are people who read and understand very quickly everything that is written. I read slowly, word by word; it takes time. I told myself that there might be others like me [who take time to read]; [the text] will delay people in front of my painting. This is what I wanted. This was not the case with my colleagues. That was the difference.

- Riason Naidoo

I’ve read that you make up to three versions of the same painting. If that is true, it is very unusual in modern and contemporary art that relies on a unique painting.

- Chéri Samba

Sometimes they ask me, “Why make the painting in several versions?” Before Chéri Samba, there were also other painters who did paintings in a series. In my case, if I paint the picture several times, it’s because there are paintings that I don’t want to sell.

If I paint a subject, I would like everyone to see it so that it circulates all over the world. I, myself, would like to keep a copy so as not to take photos or make prints, as you say. Sometimes, I wanted to do it again for myself. It happened to me that a painting that I might reserve for myself ends up in someone else’s home. There is already an existence of this subject, which is already gone. I think to myself that it is not good that I repeat the same subject for someone else who is interested. But the person concerned tells me, “No, I want that,” and there are some who asked me for the third, fourth, fifth, sixth version of the painting, and I said to them “No!” In this case, I like to limit myself to three versions, so it was not me who chose, but it is the requests that I receive that resulted in the additional versions. I was surprised that there were back-and-forth requests, demands from so-called art connoisseurs who asked me to make another version of a painting for them. So, finally, I said to myself, in order for people not to miss the work, I would have to continue. It’s not my choice to reproduce all the time, but what should I do?

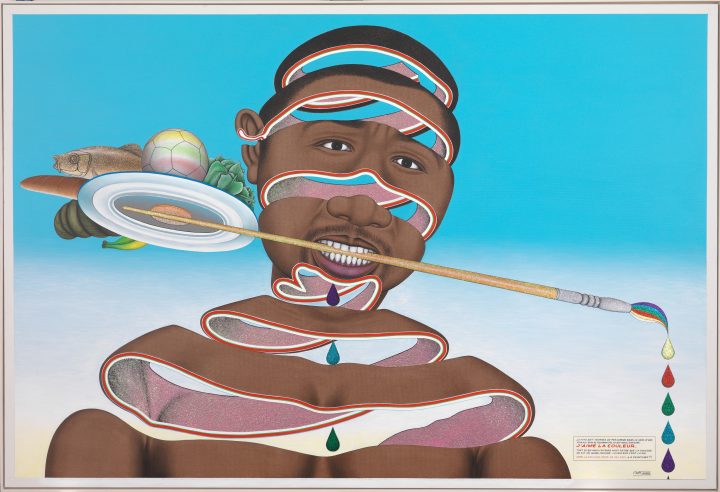

I’m talking about the painting, such as I Love Color, also the subject. I think a lot of people liked it, and it hurt me that it was only found at someone’s friends place while everyone wished to see it.

J’aime la couleur, 2010. (I like colour). - Riason Naidoo

Could you describe for me the Art partout exhibition in Kinshasa in 1978 and the atmosphere around it?

- Chéri Samba

I think it’s one of the exhibitions that also shed a lot of light on the thought that if art did not exist only at a given point in the world, it did not exist. The idea was to show that there are artists everywhere in the world; that they are not only in the West, as we used to say in the past. And what was a little ambiguous is that we thought that where there are no galleries, museums, there are no artists, and it was a false discussion. Whether there are galleries or museums, artists are everywhere, and art is everywhere in the world; that was the idea behind the exhibition [that took place in the streets].

- Riason Naidoo

What do you mean by “paintings with no soul”? What are your thoughts on contemporary art you see in museums around the world when you visit?

- Chéri Samba

I was just saying that there are things you can easily understand and things you don’t. I compared a little the work dictated by the so-called connoisseurs in the fine arts schools and there, I said, there are works, which sometimes, the people for whom the works are intended had difficulty understanding the message. It’s not to say it was well done or that it was bad—no. The message is only for initiates, art connoisseurs, insiders.

If someone wants to challenge the conscience and wants to talk with these compatriots, why code the message? This is why I was saying I would like to paint in what I would call “folk art.” Of course, the word “popular” was also not very well understood, especially in the West. People thought “popular” was without thought. We pick things up without thinking. I said that “popular” is a painting that comes from art and goes toward the people, and the people are easily recognized there. So, there is this relationship between the art understood by the people and art that is intended for the initiated, while the world belongs to everyone. For me, you have to give the message to everyone unambiguously.

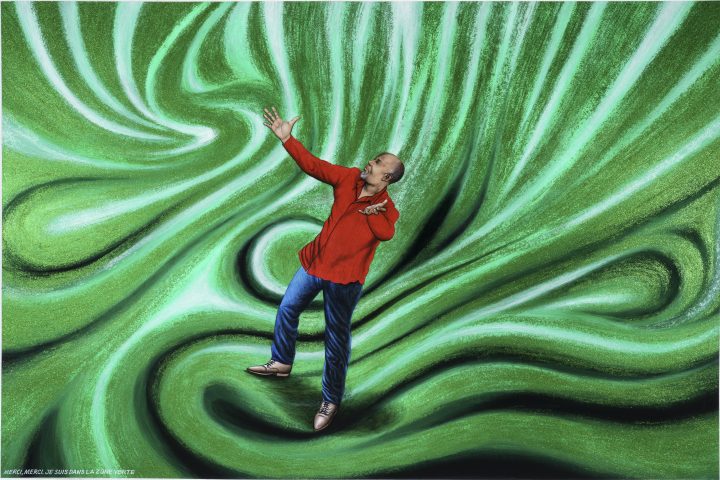

Merci, merci je suis dans la zone verte, 2020. (Thank you, thank you, I’m in the green zone) © Florian Kleinefenn. - Riason Naidoo

Is it true you wrote words in your paintings in Lingala to be invited abroad?

- Chéri Samba

Yes, it’s true, it’s not only in Lingala that I wrote, I also wrote in Kikongo, in Swahili, etc. I wanted to write the words from my country so that I would be known outside my country, then I could be invited to speak; that was the strategy.

- Riason Naidoo

Did it work?

- Chéri Samba

I don’t know if it worked, because sometimes it’s not just what I write that interests people, but what I present in pictures. This is what people see first.

- Riason Naidoo

You first met André Magnin in 1987. Tell me about that meeting.

- Chéri Samba

I saw a gentleman who arrived in my studio who introduced himself as André Magnin. He wanted to do for the very first time an exhibition, which was to bring together several artists from Africa, from all over the world, approximately 100 artists. I was chosen. He told me that I wasn’t going to do anything else. If I had a trip in mind, I must just forget about it … I just trusted Mr. Magnin, who was going to present my work at the exhibition, and it paid off. I did what he asked me to do, and we developed a mutual trust.

- Riason Naidoo

And what about the Magiciens de la terre exhibition in Paris in 1989? What was it like to be part of the exhibition? Could you describe the moment of going to Paris and participating at the Centre Pompidou?

- Chéri Samba

Magicians of the Earth was an exhibition that brought together several tendencies of artwork we were doing. There were already people who exhibited in museums, and there were others that we did not know, as if they were not artists … but André Magnin saw that this misunderstanding should not continue to exist. So, he said that he found many other artists more interesting. Why not include them in this exhibition? Like the word said, “magicians,”—people who presented incredible things but who were not recognized as artists. The exhibition pissed off a few artists, it has been said, but we will not talk about that. It was the artists at that time that André Magnin and his colleagues had found who really made the difference in that year.

- Riason Naidoo

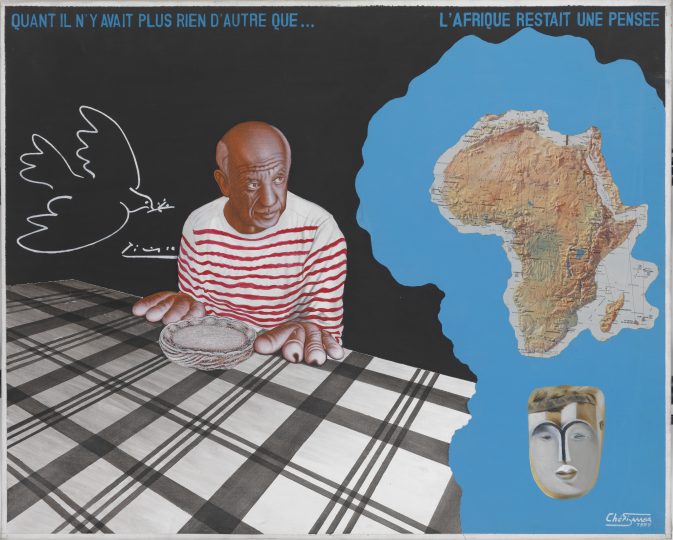

Are you a strategist and politician as well as an artist? I’m thinking of your inclusion of Europeans in your paintings, also of other artists such as Picasso, to broaden your audience.

- Chéri Samba

It’s true, I’m an artist, what I say and what people seem to ignore. Whether we are in politics or not, we are in the water. Artists also help politicians to change their position. In my opinion, it is the artists who help the politicians to improve themselves. In my work, in my country, it has paid off; it helped to make sense of politics.

You know, our policies had instituted the system of learning only foreign languages, and we ignore our languages … Everyone speaks English, German … We do not know our languages. When I was given an award by the Prince Claus Fund in 2005 in Amsterdam, it was for my satire and the recognition of the languages in my paintings. I spoke about it during my presentation and saw in the schools at home that language learning was initiated at the source. This is what I mean when I say that the artist helps the politician to improve himself. Whether we play politics or not, we are in it.

Quand il n’y avait plus rien d’autre que… L’Afrique restait une pensée, 1997.

(When there was nothing left… Africa was a thought.) © Chéri Samba Collection.- Riason Naidoo

The universal themes in your paintings (the everyday, education, politics, sexuality, humor) are part of this strategy to reach more collectors or a wider audience?

- Chéri Samba

Yes, all these themes are universal. If I look at my recent painting On est tous pareils, (We Are All the Same), 2020, I think it’s universal. In J’aime la couleur (I Love Color), 2010, I told people that we should turn our heads a bit like in the spiral to know everything around us, which is only color. Whereas there are people who ignore the notion of colors so there is only one color, black. I say that I am not black, even though I can dress in black. We were told, this is a conventional color, as if there are no other colors.

On est tous pareils, 2020. (We are all the same) © Copitet - Riason Naidoo

Why do you often depict yourself in your paintings?

- Chéri Samba

First, I think it’s a joy in yourself to know how to achieve perfect things in their exactness. If I represent a rooster, a hen, we do not see a pigeon, so there is a pride to know how to succeed in things that can surprise others. It is this representation that makes me happy and not to annoy people unnecessarily. When you present the face of yourself, you eliminate the risks. I once presented on purpose a painting with the face of a stranger. A second gentleman, and everyone who saw the artwork, said that it was the second gentleman that I had captured in the painting—that I had titled Les Abyssales [meaning, someone who hid the dirty clothes under the mattress]—which was false. For that I had paid fines, and I said to myself that I don’t need this kind of bullshit again. I don’t represent animals, so if I have to present a face, then it would have to be my own face whether I succeed or not, but it should be me.

- Riason Naidoo

How has the technique in your work evolved over all these years?

- Chéri Samba

At the time, I was able to do five or ten paintings in a week, and today when I see the paintings done several years ago, I cannot believe it. Without knowing it, I saw that the technique has changed a lot, not to say improved. My production is a lot less now. I finished a painting after a few breaks because I focus on doing small details, and this takes a lot of my time. In the past, I didn’t worry too much about depicting details, but now I do. I think that has changed a lot, in a good way.

- Riason Naidoo

And for the themes?

- Chéri Samba

I have suitcases full of ideas that I can take at any time, but it’s not so easy anymore, because I work a bit like a journalist. They work on a daily basis. I don’t have to resort to things that happened years ago because there are always new things happening. I have had a hard time dipping into my suitcase, and the suitcase fills up all the time. So, I take things that affect me from everyday life.

- Riason Naidoo

I’ve read that Escher and Picasso are references in your work. Are there any African artists who inspire you, living or dead?

- Chéri Samba

Léger, Picasso, Magritte, or anyone else are not my references. I went into this painter’s adventure without any knowledge of other artists. It was during the time that I was in the profession that I heard about these artists, and my eyes did not prevent me from seeing what they were doing.

I saw their work … and saw that it wasn’t bad, that there were things that interested me also in their technique. To satisfy myself, to cheer myself up, I thought to myself what they did, I can do too. I might not be able to compete with them, but I thought I too can do this. At the beginning, I was talking about other paintings at the art fair; those did not impress me, these artists whose works cost millions. I will not mention the names, but it is as if it was my children’s work.

The artists you mentioned are not my models, but I appreciated their work after I got into art, into this art adventure. There are a lot of artists in my country who were not my role models, but whose work I admired, such as Pilipili Mulongoy, Albert Lubaki, Pierre Bodo. There are also young people such as JP Mika, the work he presents; I had the impression that things were moving.

There was a client who asked me, can you do something that moves? I said, but how can you do something that moves in painting, like something that gives you the chills? Don’t tell me the Légers, the Picassos. They existed before me and did a good job that I admired, but that does not mean that they were my models. I am my own role model.

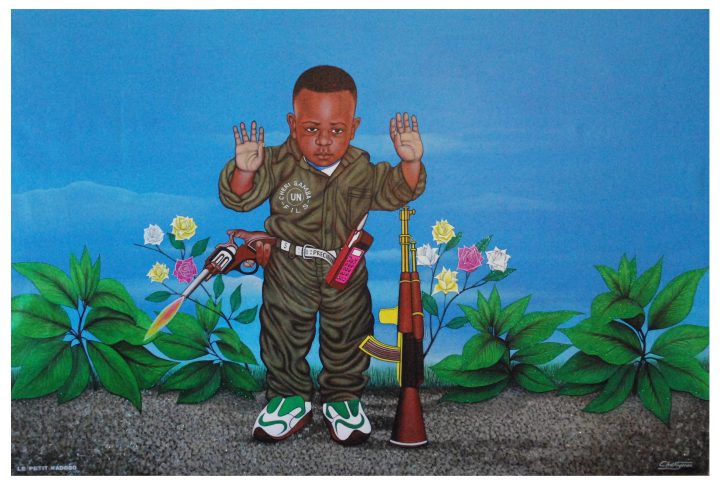

Le petit Kadogo, 2009 (Little Kadago). You know, I had three bosses before I set out on my own, but they didn’t draw paintings like me. They were people who were writing [signboards]. I don’t even know if I can call them artists. And those gentlemen there, when I was doing a painting, when I was doing a portrait, if the customer refused, my bosses weren’t able to correct where I had gone wrong. We used to say that we couldn’t work well there, because we are on the main artery; there is too much noise from vehicles [on the road]. This is why we took the work home to work quietly. And when it came back, we could see the difference. That’s why I said I didn’t have a master. It was I who pushed myself.

The interview was conducted in French in Paris on September 11, 2020, at Galerie Magnin-A. Transcription in French by Eric Mercier. First published in New Frame (Johannesburg) in October 2020.

Drip is temporary 14 Oct 2:00 AM (7 days ago)

The apparel brand Drip was meant to prove that South Africa’s townships could inspire global style. Instead, it revealed how easily black success stories are consumed and undone by the contradictions of neoliberal aspiration.

My ghetto is not your inspiration.

Lekau Sehoana’s clothing business had been around for nearly half a decade—but its sudden popularity and the humble beginnings of its founder made it look like a miracle out of nowhere. Founded in 2019, after a series of other genuine attempts at entrepreneurship, Sehoana sold Drip to consumers as the township dream; it was what happens when the enduring legacies of colonialism—and apartheid—that continue to make townships a spatial reality in democratic South Africa aren’t a factor. That tagline—the township dream—could often be seen splashed in bright letters on the company’s fleet of vehicles and the billboards that came to be at the center of a controversy that will likely come to define the legacy of a man once thought to be South Africa’s most popular entrepreneur. The poster boy of the country’s neoliberal possibilities.

In 2022, during an interview with Sehoana, popular radio presenter and podcaster Sibusiso Leope remarked that the colorful billboards advertising Drip sneakers on Sandton’s M1 road were like “an announcement of a new sheriff in town.” A relatively new and black-managed business advertising in Sandton isn’t insignificant: Sandton is the largest and most visible concentration of South Africa’s symbols of inequality. In 2019 Time magazine put photographer Jonny Miller’s drone image of a leafy Sandton neighborhood against an Alexandra township defined by the congestion of informal settlement structures on its cover. The point? Illustrating the sharp inequality that now defines much of the country. It’s in the few kilometers that divide Alexandra township and Sandton City that the country’s contradictions are most vivid. For Sehoana, advertising in Sandton was more than the pronouncement of a business or product; to advertise in Sandton is to announce both flight and arrival—like many who found success in the continent’s richest square mile—he had defied the dispiriting conditions of the working-class neighborhood that raised him. But as he would come to find out, defying spatial colonialism as a young businessperson eager to prove himself was one thing—sustaining a business was another.

There was something joyous—even exciting—about watching someone who once described himself as “a hoodrunk” realize the height of his potential. That joy was rooted in the impossibility of starting a business and holding your own. Only 1 percent of South African start-ups are said to grow to become viable enterprises. Drip was an attempt to distill an ungenerous township experience into a symbol of resilience. Its success lent weight to a broader cultural argument by some contemporary post-apartheid designers—about decolonizing the aesthetic and language—that defines the value of a cultural brand. They argued that a vernacular term and the history that tints it—stitched on a pair of jeans—can come to carry as much cultural value as a foreign luxury brand, even as its target market, elites in the South African context, seeks to mimic a Western lifestyle. Though “drip” is not a classical vernacular or indigenous term, it relied on and advanced that argument more than any other local brand that shied away from the politics of decolonial aesthetics and language.

Like any country marching to the beat of neoliberal capitalism, South Africa places great importance on acumen and sees business as a logical answer to some of its socioeconomic problems. What followed Sehoana in the wake of Drip’s liquidation were all the arguments about what he should’ve done and not done. Sehoana himself was a neoliberal crusader, often speaking of not just building a business but setting up systems that would ensure that the business outlives him. He was acutely aware of both the stakes and technicalities of turning a start-up into a behemoth. But there’s no amount of business acumen—or policy literacy—that can compensate for a poor cultural argument.

“Clothing is so close to the body, audiences take massaging from brands personally. More so, in the South African context where we already have so many issues around exclusion, audiences are sensitive to messaging that echoes exclusion as it relates to class, gender, and race,” says fashion writer and historian Khensani Mohlatlole when I ask whether a poor cultural reading of an audience or consumer base can be fatal to a business. Sehoana successfully packaged social fugitivity into a sneaker—but could not sell it at the market. As a result, Drip as a symbol of upward mobility came to be more important than Drip as … a decent product.

When he announced its liquidation, much of the discourse about Drip revolved around what everyone considered to be his obvious mistake: rapid expansion (at the peak of his business, Sehoana oversaw 18 retail stores across the country). But the most obvious mistake and inherent limit of Sehoana’s business was a lack of cultural buy-in. Many of the South African local clothing brands that have been successful in the post-apartheid era anchored their survival and success on courting or attaching to a cultural phenomenon. Mzwandile Nzimande and Sechaba Mogale exploited South Africa’s hip-hop scene to make their clothing brand Loxion Kulca synonymous with cool. On the cover art of their 2008 album Can’t Touch This members of the legendary South African kwaito group Trompies stand against a split background of tires, scrap metal, and an empty township street, a tribute to their respective working-class backgrounds. They wear Dickies’ iconic utility shirts that have come to be synonymous with certain aspects of Kwaito’s visual or aesthetic culture. It isn’t a sponsored image but speaks to the American clothing brand’s success in embedding itself with a South African cultural symbol which has ensured its success as a business. Dickies has never officially endorsed or sponsored Trompies but ask any South African which brand they associate with the group they’ll say Dickies. Or which group they associate with the brand, they’ll say South African kwaito group Trompies. It was the same reason American brand Reebok broke rank with international apparel brands’ unspoken boycott of kwaito, because despite its popularity and crossover appeal, it was essentially a critique of the exploitative conditions (“hase mo’state mo”) that attracted foreign brands to the country and offered kwaito star Kabelo Mabalane the country’s first sneaker (Bouga Luv) endorsement deal in 2005.

Sehoana joined with Southern Africa’s biggest pop star, Refiloe Phoolo, a.k.a. Cassper Nyovest, in what he called the most significant partnership ever created between a non-athlete personality and an athleisure brand rumored to be worth US$5 million. Sehoana compared the structure of the deal to that between Nike and basketball legend Michael Jordan, which made the brand synonymous with US sporting and popular culture. With that agreement, he hoped to mirror what Nike did with Jordan and Dickies did with kwaito. At the time of the signing Phoolo was still Southern Africa’s biggest star at least by the numbers. To date, he remains the only independent Southern African rapper—of his generation—to fill successive major venues, including stadiums, to capacity. But for all his cultural weight, Phoolo could neither carry nor save Drip. It wasn’t the first time a business agreement centered around a celebrity fails to transform the fortunes of a local business. In the late 2000s, South African telecommunications company Cell C, attempting to hold its own in a fiercely contested markett, decided to rope in Bonginkosi “Zola” Dlamini, then Southern Africa’s biggest pop star. For three years, Dlamini would be the face of the company and have a brand of products, as part of what was billed then as the first endorsement deal of its kind. But though popular, Dlamini’s cultural weight would have little bearing on the fortunes of the company. Sehoana seems to have been hatching his bets on the miracle of a business deal driven by the appeal of celebrity too. It might have worked, but his corporate expansion seemed to have been moving faster than he could make a cultural argument about why people should ditch their treasured Nikes and embrace an obscure label out of a South African township.

In the world’s most unequal country, everything comes down to appreciating the nuances of class and race, but aspirant capitalists like Sehoana, who rely on the allure of upward mobility as a unique selling point of their business, rarely anticipate resistance or their intentions being read critically. This is how Drip, a brand that claimed a working-class background as inspiration, ends up with billboards in one of the most affluent neighborhoods in the continent, assuming it will be read as a triumph and attract new business. It is also how Phoolo, a millionaire pop star, becomes the face of Drip when it claims to want to appeal to working-class consumers. Of course, as a businessperson in a country where the face of corruption and failure is black, Sehoana was always going to spend a disproportionate amount of time and money trying to scrub the stench of failure that comes with surviving structural issues.

The argument of a celebrity endorsement or marketing deal is that if enough elites embrace something, then ordinary people will uncritically embrace that same thing. Sehoana and Drip weren’t wrong to hatch their bet on Phoolo; he’s Southern Africa’s most significant cultural figure of the last decade. But if one listened closely, part of what went wrong in Phoolo’s partnership with Drip could be heard in his music. In the song “Phumakim” from his acclaimed 2015 debut album Tsholofelo Phoolo raps about being rich enough to transcend both the racial and class context of his upbringing. Phoolo was delivered to superstardom mainly by young black South Africans trying to escape and redefine the class context of their parents. So, it was easy to celebrate attaining wealth as a sufficient condition for social freedom, but as they’ve grown to become weary adults in the world’s most unequal country, it’s only natural that most would struggle to relate to materialism as a symbol of success. By the time Sehoana and Drip offered him a deal based on his celebrity status, the context of Phoolo’s fame was different. He was no longer the rapper who commanded the adoration of 20-year-olds who could be told to flock to Drip stores to purchase sneakers.

Phoolo’s partnership with Drip was part of a scorched-earth approach to their marketing campaign that made Drip popular even as the logical opium of the cool. But it comes undone when every cultural symbol Seohana deploys to hook the market misfires. A kit sponsorship of South African legendary football club Moroka Swallows, a collaboration with South Korean brand Fila, and another celebrity partnership with veteran house DJ Zinhle as the face of Drip’s signature perfume Finesse were all meant to inject the brand with cultural mileage. At best, those partnerships were an ode to a bygone era—Sehoana might have hoped that a bit of nostalgia and economic nationalism would endear Drip to a consumer base. But love and nostalgia are not tangible or even sustainable market goods.

At some point, Drip would have to qualify its claim as a business that is conscious of the realities of the township. Or a business that contends with the context of the environment it’s operating in or its market, in Drip’s case, the grit of township life. Sehoana sang praises to the township as an inspiration for Drip, but what seemed to have got lost in the liberal hymn of upward mobility is that townships are ultimately war zones. That people have made a life and community out of a township doesn’t alter the fabric of its reality: Poor policing and underfunded public health facilities mean death stalks every township corner. Overcrowded classrooms and a lack of recreational activities mean a disrupted childhood. Sehoana sold hope in a market saturated with hope dealers—when he should’ve been selling survival. Root of Fame (ROF), Phoolo’s signature sneaker and Drip’s most popular offering, is a case in point. ROF teased comfort but it’s quite clear from its design that a sewerage-spilling township street was not a factor in that process. The township of Sehoana’s imagination is not a place intentionally starved of resources to function effectively as a cheap labor camp but a portal of social possibilities. That might have been his most fatal mistake.

It’s not that Drip was above failure—life’s greatest teacher is often failure. In many cases, it’s even necessary—but Sehoana carried a different weight; the burden of culture. He was not allowed to fail in all the normal ways a person might fail. He was not a cultural immigrant. Unlike corporations, he didn’t have to exploit or harvest the intimacy and genius of the township to sell his product. More than anyone, he should’ve known the limits of his argument; one can only go so far with the narrative of triumph.

Making space for the ordinary 13 Oct 4:00 AM (7 days ago)

MADEYOULOOK’s 'Dinokana' debuted at the 2024 Venice Biennale. Now back home, Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho reflect on sound, place, and why their work is always meant for South African audiences first.

MADEYOULOOK is an interdisciplinary collaboration formed by Nare Mokgotho and Molemo Moiloa. The two met while studying art at WITS University in Johannesburg, where they graduated in 2009. The work Sermon on the Train, a series of public readings on Johannesburg trains, dates back to that period. Fifteen years have passed since then, and they continue to meet weekly to exchange ideas and implement projects.

Like other black South African artists of their generation (they were both born in the late 1980s), they say the origin of their work was “in response to the feeling that the university, and particularly the art school, did not consider our context.” Over the years, their work has explored different languages—they often call it “undisciplined”—but has kept long-term research and collaborations as its methodology, and the everyday life practices of black people in South Africa as its focus. Their project, “Quiet Ground,” was selected by curator Portia Malatjie to represent South Africa at the 60th Venice Art Biennale in 2024.

MADEYOULOOK’s “Dinokana” is a 20-minute, 8-channel sound installation that explores the cultural significance of rain and water in traditional South African life. The soundscape is experienced within a constructed environment, which alludes to Bokoni’s terraced hillsides, and where visitors can sit. The artwork takes as its point of departure the histories of the Bahurutse and Bakoni, and their cycles of displacement and return. It includes clippings of the resurrection plant, a symbol of healing and resilience linked to rain, traditional medicine, and regeneration. It is possible to see the work at Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation until November 15 as part of the exhibition “Structures” curated by Stephen Hobbs, Rebecca Potterton, and Wolff Architects. The project is divided into three sections: Situatedness, Infrastructures, and Typologies. Together, the works examine the relationship between space and subjectivity through the lenses of translation, memory, heritage, and migration; investigate how architecture—both formal and informal—embodies power and ideology, contrasting ideological frameworks with iconography; and explore the sensorial and abstract dimensions of personal and collective practices and rituals in both urban and rural contexts. The exhibition features: Igshaan Adams (ZA); Kader Attia (DZ/ FR); Kamyar Bineshtarigh (IR/ZA); Jellel Gasteli (TN/FR); David Goldblatt (ZA); Kiluanji Kia Henda (AO); MADEYOULOOK (ZA); Matri-Archi(tecture) (ZA/CH); Hélio Oiticica (BR); Hajra Waheed (IN)

In Section 3: Typologies, Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho from MADEYOULOOK present “Landscapes of Repair,” where they discuss their interest in everyday black practices in South Africa, and reflect on their understanding of what it means to have a relationship with nature. They speak about sixteen years of working collaboratively and highlight several of their projects. Molemo and Nare also share insights into the process behind their multimedia installation “Dinokana,” which was commissioned for the South African Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2024 and can now be experienced in South Africa for the first time as part of the “Structures” exhibition.

In this conversation, conducted online in March 2024 as part of “Southern Thought on a Northern Biennale” project, Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho discuss their interest in everyday black practices in South Africa.

- Laura Burocco

How did you start working as a duo, and how would you describe your practice?

- Molemo Moiloa

We met at university, and we shared a similar feeling. It just felt like there was a whole other art world beyond being at that university. It just didn’t connect with it at all. And so in a way, our initial way of working together was a very reactionary kind of thing, and very much engaged with public space as well. And that shifted over time. I think the thing that’s stayed cool from that period has been this idea of working with the everyday and thinking about sort of everyday black life as a kind of locus of thought and intellectual production. So that continues… We both had jobs and, therefore, were able to just keep working independently. So we would meet every Thursday. We have done that pretty much for the last 15 years and made projects over very long periods of time. Usually, our work is very research-based, and it is very iterative, like a lot of our projects have many, many versions. And it has definitely informed the kind of way of working, in the sense that our work is very project-based. It’s often quite multi-modal —like we’ll have a large discursive programme, we will have sort of exhibition practices, and then we will have writing practice, all related to certain ideas. And that’s because we’re more interested in the exploration of ideas than necessarily developing pictorial representations that go on walls.

- Laura Burocco

When describing your works, reference is often made to “practices of everyday life of black people in South Africa,” but also the defamiliarization with this everyday life. Can you develop more?

- Nare Mokgotho

I think some of the art comes out from the disquiet we had with our arts education. So, almost feeling like our lives, and black life in general, was kind of underrepresented in our education […] and to have that feeling that what you’re speaking about doesn’t really constitute knowledge can be quite a damaging feeling. But also to have that legitimized by someone who’s nodding as you’re speaking and who has a similar kind of somatic and lip experience as you, and can interpret things that others may not be able to see, and begin to legitimize that as knowledge, I think, is again very powerful.

The way of working around defamiliarizing I think is to look at things that you see again and again and again in a slightly different way […] And so what our practice has really been about is actually taking very familiar practices to us and relooking them and going actually, “hang on, there’s so much more going on here than we ourselves actually even understand.”

- Molemo Moiloa