TechWhirl Fast 5: Future-Proof Your Skills in a world of Budget Cuts and A.I. 26 Sep 1:31 PM (last month)

Details

- Date: Tuesday, Oct 28 2025

- Time: 11 CT

About the Webinar

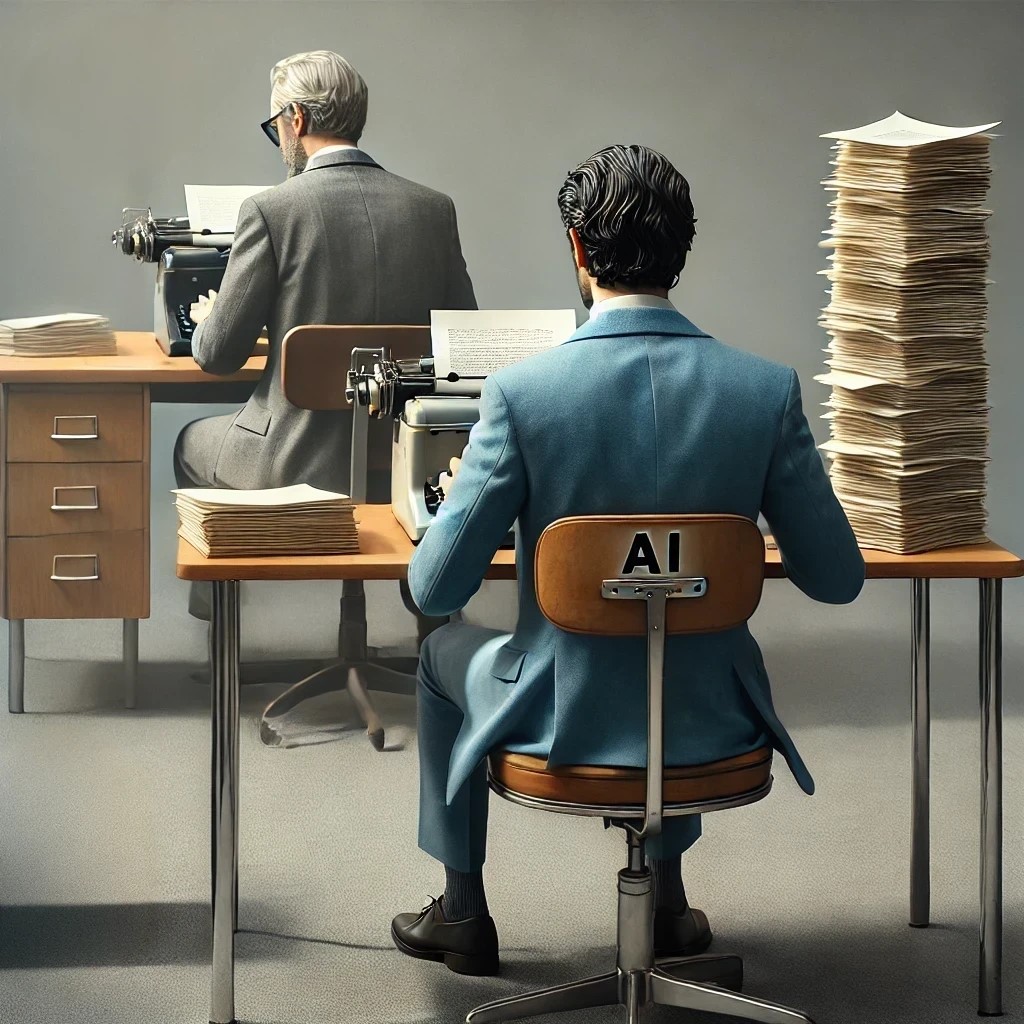

The professional world is changing fast. Faced with simultaneous budget reductions and the rapid rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI), the pressure is on to prove your indispensable value. Routine tasks are being automated, and every job function is under scrutiny.

This isn’t a time for panic—it’s time for strategic skill enhancement!

Join experts from Northern Arizona University (NAU) and TechWhirl for our next TechWhirl Fast 5 designed to give you a clear roadmap for success. Or, at least a few good ideas to consider.

In this session, we’ll tackle two major pressures: limited budgets and the rise of AI. We’ll discuss how to make your skills irreplaceable by focusing on core human strengths like creativity, ethics, and critical thinking. We’ll talk about how to use AI effectively as an efficiency tool for key tasks—not just playing with it, but getting real results using methods like prompt engineering.

Sign-up for reminder

TechWhirl Fast 5 Sign-Up – 2025

Sign-Up and submit a question for our next TechWhirl Fast 5

- This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Please remind me about the following session:

- We never share data so your information is safe with us.

Review: Environmental Preservation and the Grey Cliffs Conflict: Negotiating Common Narratives, Values, and Ethos 27 Jul 12:37 PM (3 months ago)

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) manages Tennessee’s Grey Cliffs lake and wilderness to control flooding and generate hydro power. For generations, it’s also been a beloved recreation area. At the time of Kristin Pickering’s study, ACE was considering closing the area in response to increasing damage to the land and crime rates; the community disbelieved those problems were serious and longed to keep the area open. These conflicting narratives created a communication challenge: to unite polarized people and create a shared vision of their mutual future. Turning that vision into a consensus narrative required building trust and empathy among stakeholders.

Pickering begins by thoroughly explaining her study’s theoretical context and approach—invaluable for anyone designing similar research. She provides many quotes from key actors to illustrate their diverse opinions and personalities, gradually revealing hidden shared values that eventually brought them together. For example, ACE is responsible for protecting the values residents found important (e.g., access to the site in perpetuity); clarifying this for the residents’ changed confrontation to cooperation.

Pickering notes the particular importance of establishing shared narratives “before” proposing actions. Sharing power proved essential, since actions persuade better than words alone. Part of that power lies in discussion leading to a shared narrative; that narrative provides context and values that subsequently guide everyone’s actions. Narrative also accounts for individual identities and a common purpose; it’s dangerous to challenge these identities or their underlying values.

One flaw in such studies is they lack triangulation (cross-checking researcher interpretations); Pickering acknowledges her potential bias but did not triangulate to correct it. Another flaw is that although some academic jargon is justifiable for academic audiences, the book’s difficult reading if you’re unfamiliar with phrases such as “heteroglossic narrative” (p. 12) or “created more reciprocal unity through aligned sustainability” (p. 35). A glossary would have been helpful for non-academics. And there’s no excuse for “fallen out of alignment with compliance” (p. 85) when the meaning is “broke the law.”

One key message is that except for specific discourse communities (e.g., scientists), appeals to authority and experience are less effective than appeals to shared goals, emotions, and values. Communicators must establish dialogs based on trust and respect, achieved, in part, by negotiating agency (the power to act) and ensuring all stakeholders are heard—a challenge when several communities coexist (“polyphony”). Chapters end with well-supported recommendations on how to reach and enlist multiple audiences (e.g., scientists, residents, governments). In-person communication proved crucial, even in our social media age. Trust also required “walking the talk” (leading by example), something that only becomes explicit late in the book (p. 190).

Quibbles aside, Environmental Preservation and the Grey Cliffs Conflict: Negotiating Common Narratives, Values, and Ethos provides an excellent, well-grounded example of how people cooperate to define a problem and solve it together through rhetorical techniques such as establishing credibility and trust.

Environmental Preservation and the Grey Cliffs Conflict: Negotiating Common Narratives, Values, and Ethos. Kristin D. Pickering 2024. Utah State University Press. [ISBN 978-1-64642-574-7. 238 pages, including index. US$31.95 (softcover).]

Review: Revising Reality: How Sequels, Remakes, Retcons, and Rejects Explain the World 19 Jun 8:34 AM (4 months ago)

In the modern “fake news” era, “facts” are increasingly flexible rather than tangible, provable, stable things. People increasingly accept opinions and gut feelings as more valid than expert knowledge and documented fact. Communicators working in this context require an understanding of how audiences revise reality to agree better with prior beliefs.

In Revising Reality: How Sequels, Remakes, Retcons, and Rejects Explain the World, Chris Gavaler and Nat Goldberg introduce four main ways we establish our reality: sequels that build on previous history, remakes that create new versions of that history, retcons (retroactive continuity) that reinterpret history (not always based on new facts), and rejects that deny that history.

All four revision types influence how audiences respond to communication: if we challenge their self-image as intelligent and informed, they’re likely to resist our message. To communicators, the precise definitions of the four revision strategies are less important than their implications: audiences respond to messages by revising their worldview. Audiences often oppose revision because repeatedly updating one’s understanding of the world is stressful. Revising Reality demonstrates how wording that seems clear and precise is reinterpreted, particularly after years pass and assumptions change.

I’m not sure that the term “retconning” offers advantages over “reinterpreting,” and one flaw in the book’s approach lies in separating retcons from sequels when both may be simultaneously true. For example, Einstein’s relativity is a sequel to Isaac Newton’s laws of motion, which remain broadly valid, but retcons Newton by clarifying how Newton simplified a more complex reality.

Revising Reality is a rigorous but non-academic book, so it’s highly readable, though the authors sometimes use pop culture terms such as “fanfic” and “canon” you might need to Google, and commit unnecessary abbreviations such as OT (“original trilogy”). The authors exploit their impressive knowledge of pop culture (superheroes, Sherlock Holmes) to explain the four methods, then provide historical, legal, and scientific examples of how history is reinterpreted and re-expressed. For example, did the United States originate in 1776, with the Declaration of Independence, or in 1619, with the first African slave’s arrival? In the United States Constitution, does “all men” refer to humanity as a whole, or only property-owning white men? The answers depend on one’s perspective. Using examples from diverse perspectives, the authors show different ways to understand how we revise reality. A metaphor’s power lies in how well it helps us understand. Revising Reality clearly, if metaphorically, describes how history and human memory work. Unfortunately, the authors don’t tell us how that understanding would improve communication. However, they do make it clear that if we want to change minds, sequels may be more effective than remakes, which in turn are more persuasive than retcons.

Revising Reality: How Sequels, Remakes, Retcons, and Rejects Explain the World Chris Gavaler and Nat Goldberg. 2024. Bloomsbury Academic. [ISBN 978-1-350439-64-1. 314 pages, including index. US$24.95 (softcover).]

Review: Slow Productivity. The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout 20 Apr 12:00 PM (6 months ago)

Most technical communicators have worked for employers that mistook activity for productivity and have tried to teach our bosses the difference between churning out words and crafting useful information. In Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout, Cal Newport proposes that slowing down what we’re doing improves our work quality. He notes that Henry Ford’s assembly-line principle of defining productivity as maximizing output (things) per unit input (time) fits the knowledge age poorly, as quality is more important than quantity for most of our work.

Estimating productivity based solely on visible activity (pseudo-productivity) is, as Shakespeare noted, “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” Knowledge work is hard to quantify, and Newport doesn’t solve that problem. Instead, he focuses on improving work quality through slow productivity: organizing knowledge work so it’s more sustainable and meaningful. He proposes that we do fewer things, work at a natural pace, and obsess over quality.

Newport explains these principles through tales of personal discovery, supported by anecdotes that introduce or support key points. Although anecdotes are a good tool for clarifying principles and making them memorable, they’re problematic: the “moral” may be plausible, but without a body of supporting evidence, we can’t know how generalizable it is to other situations. Scores of initially exciting anecdote-based management books have vanished without a trace when their advice proved problematic. Anecdotal evidence isn’t necessarily wrong, but it’s always context-dependent.

Many suggestions seem questionable. For example, doubling a project’s scheduled time to provide breathing room isn’t plausible in most workplaces. His example of a laboratory with an analytical bottleneck seems best solved by adding capacity rather than the author’s proposed “pull-based” process (p. 101). His comparison of industrial agriculture with hunter–gatherer cultures, which feed people efficiently and well, depends heavily on context; hunter–gatherers can’t support extremely large populations because they harvest insufficient food per unit area. These examples reveal a consistent problem with Newport’s solutions: most bosses and clients don’t let us set our own priorities or decline boring tasks. Most jobs require a certain output quantity, even if quality suffers. Although Newport mentions the need to avoid distractions, he doesn’t support this by discussing Mihály Csíkszentmihályi’s concept of “flow” (a state of highly productive hyperfocus on a task).Newport clearly explains the difference between productivity based on activity or on results. As a desideratum, Slow Productivity describes how to make the knowledge workplace more humane and quality-focused. But his suggestions fail to balance the competing needs for quantity and quality, and several suggestions are suspect. Nonetheless, if you consider his advice with appropriate skepticism, you’ll likely find several ways to improve your productivity.

Slow Productivity. The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout

Cal Newport. 2024. Portfolio/Penguin. [ISBN 978-0-593-54485-3. 244 pages, including index. US$30.00 (hardcover).]

Creatives turned tech writers 23 Feb 10:41 AM (8 months ago)

As a creative, I struggle at times with many stereotypical issues other creatives face in the technical writing field. I work best at night, my brain is thinking of zillions of things at once, I generally don’t do things in a linear fashion, and my creativity sometimes inhibits the project’s need for clarity. As a creative, I wish that my audience would have an experience though having an emotional experience isn’t the ideal outcome for the project.

Other issues that creatives struggle with include transforming their language from the figurative to the literal, using too many words when fewer are required, working with colleagues who seem more serious or literal than you, and struggling to meet deadlines. You may relate to some or all of these issues. Ultimately, if you are a creative entering the technical writing field, you face various and unique struggles.

You also most likely have critical skills that others may not be able to fill:

- High level of adaptability and a visionary, holistic diagnosis of projects and objectives

- Affinity for continuous quality assurance and process improvement

- Positive approach to handling constructive criticism

- Ability to view the content experience from the audience perspective

While turning your creativity into a usable technical skill can prove challenging, you can meet the challenges by working on the areas that may cause difficulty before they become problems.

Adaptability: Going from global to linear work styles

At the beginning of my career, I worked with a client and had a typical information gathering meeting. During our first hour-long meeting I did what I always did and asked him questions about the project that seemed to him random and unconnected. His initial patience devolved to frustration with the randomness. He said to me, “You should just give me a list of questions to answer instead of this.” Although working linearly conflicts with my natural style and personality, I learned that while working with clients, the steps we take need to make sense to them.

You can work through this challenge by documenting your process. Ask yourself, what are the steps you need to create this project from scratch? Which elements require you to be in your creative, nonlinear state to get it done versus a linear approach to gather information? If there are times when you must ask random questions to gain a deeper knowledge of the subject and the project, make your client aware that this is part of your process of creating the best outcome for their needs. Give them a time limit (30-45 minutes) and if they begin to feel frustrated, write down your questions and break up these sessions into smaller chunks.

When vision overwhelms your client

As a creative, you are most likely a visionary. You can see the entire project before it’s finished. This is an amazing skill, but it can frustrate you if others can’t see it, and it may frustrate your clients who perceive that you are speaking over their heads.

There are times when we creatives want to share our thoughts and our vision with our clients all at once. We want them to join in our excitement for the project so they can see what we see. This can be beneficial to some clients but not all.

We must remember that most of our clients seek our help to do this–to make their desired outcome into a reality. Some clients have tried to complete the project on their own but found themselves stuck in the first steps and couldn’t move forward. They realized that they need a visionary like you to complete the project successfully.

Sharing your vision all at once can be overwhelming and frustrating for them. While providing a summary of how the project will proceed is important, you are doing them a service by taking on the bulk of the project. Reassure them that you will only use their time when absolutely needed. Look for ways to share small bits throughout the project and wow them at the end with the final result.

Manage misconceptions and expectations

One of the most common problems writers encounter when working on someone’s project is that when the client sees the finished product, they think it was easy to do. They sometimes say, “Well I could have done that.”

While we are under a microscope in managing the project, clients don’t often see how much brain power, experience, editing, and attention to detail it took to get the project to look seamless. I solve this problem by periodically asking my clients strategic questions that I think may overwhelm them, and for which they may not know the answer. I have had clients respond to these questions like, “Well, what would you do?” This type of response is ideal.

This is not a trick to overwhelm them, but an opportunity to both work through the possibilities verbally and to get them to see the complexity of my thought process behind their project. Instead of them thinking, “Well, that was easy” at the end of the project, I want them to think, “Wow that was more complicated than I realized, and you handled it all well.” These strategic question and answer sessions also give me time to verbally process how to overcome obstacles.

Ultimately, time and experience will allow you to bridge the gap between your creative brain and technical writing projects. As you continue, document your process, note areas of improvement in clarity, and continue to grow with each project you complete.

Fast 5 Replay: Navigating the convergence of creativity, technology, and AI 3 Nov 2024 6:28 PM (12 months ago)

View our most recent TechWhirl Fast 5, featuring Dr.Erika Konrad from Northern Arizona University, and students Chris Farmer and Jessica Lewis, where we discuss their perspectives on creativity and technology, especially the use of AI as the technical writing profession continues to evolve.

Note: TechWhirl hosts Al Martine and Connie Giordano generated this summary from ChatGPT, and then edited it with the perspective of those who took part in the webinar.

AI and the future of technical writing: embracing change and ethical considerations

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) continues to revolutionize almost every industry, and technical writing is no exception. In our October TechWhirl Fast 5 webinar, the panel delved into the convergence of creativity and technology, exploring AI’s impact on technical communication and its ethical implications.

AI as a tool, not a replacement

A key takeaway from the webinar was that AI should be viewed as a tool to augment human capabilities, not Feared as a replacement for writers. Chris Farmer, an AI trainer who is studying at NAU, emphasized that while “AI can automate certain tasks, it still requires human oversight and critical thinking.” He reminded us that AI models are prone to “hallucinations” and biases, highlighting the need for human intervention to ensure accuracy and ethical output.

Jessica Lewis, a fellow NAU student who is also an instructional designer, underscored the unique value that creative professionals bring to technical writing. Their ability to see the big picture, connect with audiences, and bridge communication gaps between technical and non-technical stakeholders remains irreplaceable. “AI cannot replicate the human touch in communication, especially when it comes to tone, delivery, and empathy.”

Ethical considerations and responsible AI use

The webinar also shed light on the ethical considerations surrounding AI in technical writing. Connie stressed the importance of responsible AI practices, including addressing issues such as intellectual property, privacy, bias, and potential misuse. She advocated for establishing clear guidelines and guardrails in commercial, non-profit, academic and government environments to protect users and ensure ethical content creation.

Erika shared her experiences using AI for formatting tasks, emphasizing the importance of experimentation and continuous learning for writers, which is a central focus in NAU’s latest professional writing course. She encouraged writers to explore AI’s potential while remaining mindful of its limitations and ethical implications. Al concurred, using examples from his experience as a project manager in software development where he analyzes market conditions and organizes elements in UI using information processed by AI.

The future of technical writing

Technical writing and all business communications will no doubt change rapidly as AI becomes more ubiquitous. Panelists predicted that AI would continue to automate routine tasks, allowing writers to focus on higher-order activities such as content strategy, user experience, and relationship building. Connie also noted that working with AI can strengthen basic technical writing skills. “Building better prompts by experimenting builds your skills as an interviewer who can ask probing and complex questions.”

Jessica summarized her perspective, “With large businesses that are simply providing information, it may be okay to continue to use AI, but individuals or entrepreneurs will still need to be unique and surprising in order to connect to people’s hearts and desires.”

Chris concluded by reminding us that, to thrive in this evolving landscape, technical writers are encouraged to embrace AI as a tool, develop skills in prompt engineering, and stay abreast of emerging technologies. Continuous learning and experimentation will be crucial for writers to adapt and remain competitive.

Creativity, technology, and AI: Conclusion

The TechWhirl Fast 5 webinar offered valuable, real-world insights into the convergence of creativity, technology, and AI in technical writing. While AI presents both opportunities and challenges, its responsible and ethical use can significantly enhance the field. By embracing AI as a tool and upholding ethical standards, technical writers can navigate this transformative era and continue to produce high-quality, user-centric content that meets the needs of a rapidly changing world.

Also on TechWhirl

Behind the scenes of AI training: Insights from a freelance contributor

TechWhirl Fast 5: Beyond the Hype: AI for Human Writers & Editors

Behind the Scenes of AI Training: Insights from a Freelance Contributor 16 Oct 2024 8:55 AM (last year)

Image by Chris Farmer, generated by AI

This recent interview between Erika Konrad, of NAU and student Chris Farmer, goes in depth into the world of AI contributors and training.

Chris, I understand that you are an AI trainer. What does that mean?

AI Contributor might be more accurate; I provide data that is used in AI training. I’m definitely not a software engineer! That said, I’ve participated in several projects that are making AI better. I spend approximately fifteen hours per week working as a freelance contractor, delivering data used for RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback).

Different skill-sets are required depending on the project. My background and education places me in the category of a “generalist.” Most liberal arts majors will find themselves in this category, which requires good critical thinking and the ability to process information across a variety of fields. The other categories are STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) and Coders. Generalists might work on STEM tasks, but often those tasks require more advanced knowledge; examples can include solving complex calculus equations or physics problems like calculating the distance traveled by a particle. Coders have knowledge of programming languages, and they evaluate prompts asking the model to explain everything from creating lines of code in Python to understanding function parameters in TypeScript—please don’t ask me to explain what that means because I can’t!

I get shifted around a lot based on customer needs, but examples of projects I’ve worked on include reviewing the quality of AI outputs, grading outputs against each other and justifying my preferences, crafting ideal responses for user generated prompts, and writing prompts designed to push the model’s limits—sometimes including an ideal response for those as well. Other projects involve identifying the explicit and implicit requirements to fulfill prompts and creating lists of those requirements for models to learn from. Prompts are the requests or instructions given to the AI. Prompts might give the model specific task directions, like summarizing a lengthy essay using a certain number of words or formatting data in a specific way, or they might give the model a role to play—like a comedian with the personality of Edgar Allan Poe. You’ll hear some interesting stories from that persona…

I’ve also served as a reviewer, verifying and editing the work of others, and as an auditor performing QA checks on data prior to its delivery to customers. I get shifted around a lot based on the needs of the company I’m freelancing for.

What are you learning from your AI training work that relates to technical and professional writing?

It has really improved my attention to detail and my research skills. There’s little tolerance for grammatical errors, because we must provide quality data for models to learn from. So, that requires meticulous attention to detail. I also research outputs across a variety of topics, and that can mean exposure to subjects with which I’m not familiar. Processing large volumes of information and conducting research to understand content across a variety of domains, all within a limited timeframe—I’m on the clock after all—seems like a skill-set that can benefit any writer.

I’m also learning to appreciate conciseness. A response with too much verbosity can be as bad as an overly short—and therefore uninformative—response. Additionally, viewing responses side-by-side builds a keen awareness of consistency. Responses that use similarly structured headings, boldface formatting (not too much), and don’t needlessly shift between ordered and unordered lists, tend to be easier to read than responses that ignore these factors.

Improved context and time savings also contribute to AI advantages

I think AI can be a timesaver for writers. You have to validate its outputs (at least for now…), but that can be easier than researching data from scratch. Especially if you ask it to provide references for its statements—it might lead you to a source you wouldn’t have otherwise discovered. That said, don’t assume that the references it gives will contain the information it provided—or that they will even exist. Test every link, and be wary of data that you can’t locate. The information might still be correct, even when the model provides hallucinated references, but it’s always up to you as a writer to validate your sources.

AI can also aid in understanding content. If writers find themselves generating content related to a field in which they have limited expertise, AI can help them build a baseline understanding of the topic, and it’s good at summarizing data and converting complex jargon into clear language. For example, I recently took an elective called Rhetoric and Writing in Professional Communities, and the coursework involved reading Michel Foucault’s The Archaeology of Knowledge, a very “heavy” philosophical book about knowledge and discourse. After reading passages and forming an understanding of the content, I asked AI to analyze the data. Sometimes, it reconfirmed my interpretation. Sometimes, it gave an output that I dismissed as completely wrong. And sometimes, it led me to view the data differently and acquire an insight that I wouldn’t have formed on my own. I think that’s an area where AI has the potential to help people grow.

When I read something, I form an understanding of the content based on my unique perspective and experiences. I might study an analysis from another individual and learn from their perspective, but I only have so much time. AI can process tremendous amounts of information, and it can output one or several interpretations of the content based on all the information it processes. People might argue that those AI outputs can be incorrect, but so too can the outputs that people produce. AI makes mistakes, and you need to verify what it’s saying (again, for now…). But it can help writers understand content, and it can process substantial amounts of data quickly.

What challenges are you finding in AI training work?

I think I’ve mentioned the biggest one a few times, and that’s accuracy. The models are only as good as the data they’re trained on, and the internet often contains data that at best is partially correct and at worst is completely incorrect. AI can process a lot of information, and it’s gotten good at understanding the patterns of our language enough to predict the next word, phrase, or paragraph that it should present to us based on our inputs, but we have to question its outputs as much as—if not more than—we question any other information we come across. I recommend viewing AI as a source similar to Wikipedia; it’s probably correct, it can improve our understanding of a variety of topics, and it can help us find additional references, but I wouldn’t consider it a scholarly source, and I wouldn’t cite it in any formal document.

One recent example involves completions I was grading from a model. The initial prompt asked what “mission command” was. The model gave an answer, and then the user asked about how the Army defines the “principles of mission command.” The model output a response listing the “six” principles of mission command. I validated the response, and my initial web search showed multiple websites that list those six principles. However, as I scanned the search results, one caught my eye that mentioned seven principles. This article led me to Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 6-0, where I learned that there were indeed seven principles. Only a few outputs produced by the model gave the correct answer. Of course, I graded the correct answers as the preferred responses, so hopefully the model will stop making that error when my training data is uploaded, but this is an example of where the model is only as good as its data.

Of course, given that there were many online articles giving answers that were not fully correct, a human might have made this mistake too, but a human is also more likely to find the correct answer in the haystack of misinformation that is the internet (repeating myself again when I say: for now…)

I feel that some professional and technical writers are panicking about AI and that some managers are jumping on the AI bandwagon just because it is the latest “thing.” What are your insights about that?

I agree that managers are “jumping on the AI bandwagon,” at least from what I’ve seen. My wife generates online content for a company, and she’s been instructed to shift from creating all of her own content to editing AI generated content. She is still producing quality work, but AI is doing a lot of the heavy lifting. My understanding is that the company she works for had to shift to using AI in order to keep up with competitors who were producing more content at a faster rate. This illustrates the pressure managers are under; if companies don’t learn to leverage AI, they risk being left behind by those that do.

I have to add a disclaimer here that aside from my wife’s situation, my experience with this is limited. I’ve read a lot of articles discussing the subject, and two themes appear often:

- Businesses shouldn’t use AI just for the sake of using AI, but they should explore how it might solve specific problems.

- Many businesses already have AI projects underway, and those that don’t may need to evolve to keep up.

The same goes for professional and technical writers. They still have an important role, but they need to learn to use the new technology, or they may be left behind by those that do. The best thing writers can do now is to practice with AI—learn to craft prompts that produce desired outputs. I said earlier that AI is only as good as the data that goes into it, but this isn’t 100% true. AI is also only as good as the quality of the prompt. Sure, simple tasks can be carried out with simple prompts. But crafting detailed prompts that produce quality outputs again and again is its own art, and I suspect that in the future, some of the best writers will also be adept prompt engineers.

How did you get started working with AI?

A lot of companies currently advertise jobs for AI trainers. I received a communication from a recruiter through Handshake, a job site geared toward students, that I joined through my university. The easiest way to find companies that are hiring is to search for “AI training jobs” or “RLHF jobs” online. Of course, there’s a lot of competition for remote jobs, and you need to research any company you are considering. I definitely recommend doing a Reddit search for the company name and reviewing comments—with an understanding that people often only write about a business when they have something negative to say, so the view may be skewed. Still, it’s worth reviewing the data. Unfortunately, not every job advertised online is legitimate, so be careful if you pursue any remote job. Fortunately, my experience has been positive!

Christopher Farmer has served in the US Navy for 25 years and is pursuing a MA in Professional Writing from Northern Arizona University. He has a background that includes managing teams and working with technology, and he is a Certified Postsecondary Instructor (CPI). He has also earned a BA in English from Thomas Edison State University and a BS in Liberal Arts from Excelsior University.