Hobbies and Interests Exercises (Fun ESL Practice for Beginners) 12:18 AM (last hour)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Talking about hobbies and interests is one of the most enjoyable ways to practice English. It helps you express your personality, share your passions, and connect with others in real-life conversations.

In this post, you’ll find fun and practical exercises to help you improve your vocabulary, speaking, and writing skills. These vocabulary and speaking activities are designed for students and teachers. They are perfect for both classroom use and self-study.

1. Multiple-Choice Exercise: Hobbies and Interests Vocabulary

Test your understanding of common hobby and interest words. Choose the correct answer for each definition.

"Hobbies and Interests"!

Test your English skills with this Hobbies and Interests Exercise.

-

Read each question carefully.

-

Choose the best answer from the four options provided.

Example:

This hobby refers to the activity of catching fish, either for food or as a sport:

- a) Reading

- b) Fishing✅

- c) Running

- d) Photography

Time's up

2. Speaking Exercises: Talking About Hobbies

Now that you know the vocabulary, it’s time to use it! Practice these speaking activities to improve fluency and confidence.

Exercise 1: Pair Interview

Work with a partner and ask each other:

- What do you like to do in your free time?

- How often do you do it?

- Why do you enjoy it?

- Who do you usually do it with?

Then introduce your partner to the class:

“This is Sam. He enjoys playing football because it helps him stay active.”

Exercise 2: Find Someone Who…

Move around and find classmates who match the descriptions below:

- ✅ loves outdoor activities

- ✅ plays a musical instrument

- ✅ enjoys cooking

- ✅ likes reading novels

- ✅ is learning a new hobby

Ask follow-up questions to learn more!

Then, write a report about your partners’ hobbies and interests.

Exercise 3: Role-Play Conversation

Choose to be A or B:

A. Imagine you meet someone new at a social event. Use phrases like:

- “I’m really into…”

- “I started [hobby] when I was…”

- “It’s a great way to…”

Example:

“I’m really into photography. I started a few years ago, and I love capturing nature and people’s emotions.”

A. Express interest in your partner’s hobby and say what activities you like doing, when, and why:

“Oh that sounds interesting. I like photograpy, too. But I enoy fishing more. I go fishing on Sundays. It makes me feel relaxed.”

Exercise 4: Talking and Writing about Hobbies and Interests

Part A – Model Conversation

Read the short dialogue between Anna and Ben.

Anna: My favorite hobby is swimming. I started when I was a child, and I go to the pool twice a week. It keeps me fit and helps me relax.

Ben: That sounds great! I enjoy playing the guitar in my free time. I’ve been learning for about three years.

Anna: Wow, that’s interesting! How often do you practice?

Ben: Almost every day. It helps me forget stress and express myself through music.

Answer These Questions:

- Who likes swimming? When does he or she go to the pool? Why?

- Who loves playing the guitar? When does he or she practice it? Why?

Part B – Your Turn

Now, work with a partner. Take turns asking and answering questions about your hobbies and interests. You can use these prompts:

- What’s your favorite hobby?

- When did you start it?

- How often do you do it?

- Who do you usually do it with?

- Why do you enjoy it?

- How does it make you feel?

Part C – Write a Short Paragraph

After your conversation, write 5–7 sentences about one of your hobbies. Use this structure:

- Introduction: “My favorite hobby is…”

- Details: When you started, how often you do it, and with whom

- Reason: Why you enjoy it

- Closing: How it makes you feel

Example:

My favorite hobby is swimming. I started when I was a child and went to the pool twice a week. It keeps me healthy and helps me relax. I enjoy the feeling of moving in the water after a busy day.

Exercise 5: Compare Two Hobbies

Write about two hobbies — one you already do and one you’d like to try.

Example prompt:

- Compare reading books and learning photography. Which one do you prefer and why?

3. Group and Pair Work Ideas

Activity 1: Hobby Survey

Create a short class survey:

- What’s your favorite hobby?

- How often do you do it?

- Do you prefer solo or group hobbies?

Then share your results using simple sentences or charts.

Activity 2: Hobby Poster Project

In small groups, make a poster about different hobbies. Include:

- Pictures or drawings

- Short descriptions

- Reasons why people enjoy them

Display your posters in class or post them on a wall.

Activity 3: Hobby Guessing Game

Describe a hobby without naming it.

Your classmates must guess what it is!

Example:

- “You need a ball, and two teams compete to score goals.” → Soccer

FAQs: Hobbies and Interests Exercises

How do I write about my hobbies and interests?

To write about your hobbies and interests, start by naming the hobby you enjoy most. Then, explain when and how you started it, how often you do it, and why you like it. Finish by describing how it makes you feel. Use simple, clear sentences and try to give personal details.

Example:

My favorite hobby is reading. I started when I was young, and I read every night before bed. It helps me relax and learn new things.

What are some examples of hobbies and interests?

Here are some common examples of hobbies and interests you can mention:

– Reading

– Playing the guitar

– Swimming

Painting

– Cooking

– Traveling

– Dancing

– Playing football

– Gardening

– Photography

How do you write 10 sentences about your hobby?

To write 10 sentences about your hobby, expand your paragraph with more details. Include:

– When and why you started

– How you learned it

– Who inspired you

– Where you usually do it

– What you like most about it

– How it benefits you

– How it makes you feel

– Any goals you have for the future

Example (10 sentences):

“My favorite hobby is cooking. I started when I was 10 years old, helping my mother in the kitchen. I cook almost every weekend. My favorite dish to make is pasta. Cooking helps me relax after a busy week. I also enjoy trying new recipes from different countries. My friends love tasting my dishes. I often watch cooking shows to get new ideas. I hope to take a cooking class one day. Cooking makes me feel creative and happy.”

What is the 5 hobby rule?

The 5-hobby rule is a simple idea that suggests you should have:

– One hobby to make you money

– One hobby to keep you fit

– One hobby to be creative

– One hobby to build knowledge

– One hobby to relax and enjoy life

This balance helps you stay productive, healthy, and happy.

How can I practice talking about hobbies in English?

Practice with a partner by asking and answering questions about your hobbies. Use expressions like “I enjoy…” or “I’m really into…” to sound natural.

What are good writing exercises for hobbies?

Try short writing tasks about your favorite hobby, why you like it, or a new one you’d like to try.

How can teachers use these activities?

Teachers can combine vocabulary quizzes, speaking tasks, and writing exercises for a full lesson on hobbies and interests.

Check these Free Time Activities for Kids

Related Pages

- Talking About Hobbies and Interests in English

- More Speaking Lessons

- Daily Routine Vocabulary Game

- Free Resources and Vocabulary List

- Weather Idioms Quiz

Pragmatic Competence Development in English Language Teaching 28 Oct 2:25 AM (2 days ago)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Language learning is more than mastering grammar rules and vocabulary lists. To communicate effectively, learners also need to understand how to use language appropriately in different social contexts.

This ability is known as pragmatic competence — a crucial component of communicative competence. Developing learners’ pragmatic skills helps them sound natural, polite, and culturally appropriate when speaking English.

To explore the development of pragmatic skills in language learning, it is important to understand its place within the Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) approach and the key competences it emphasizes.

Communicative Language Teaching and the Four Competences

To explore how pragmatic competence develops in language learning, it is important to understand its place within the Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) approach and the key competences it emphasizes.

The CLT approach emerged in the 1970s as a response to traditional methods that focused mainly on grammar and translation. Rather than teaching language as a set of rules, CLT aims to help learners use language meaningfully and appropriately in real communicative situations. This approach highlights that knowing a language means being able to communicate effectively, not just produce grammatically correct sentences.

According to Canale and Swain (1980) and later expanded by Bachman (1990), communicative competence consists of four interrelated components:

- Grammatical Competence

This refers to the knowledge of syntax, vocabulary, pronunciation, and spelling. It enables learners to form grammatically correct sentences and recognize how language structures work. - Sociolinguistic Competence

This involves understanding the social context in which communication takes place — for example, knowing how to speak formally or informally depending on the relationship between speakers or the setting. - Discourse Competence

This competence focuses on how sentences are connected to create meaningful spoken or written texts. It includes the ability to use cohesive devices and organize ideas logically in conversation or writing. - Strategic Competence

This refers to the use of communication strategies to overcome difficulties in expressing meaning or understanding others. Examples include paraphrasing, asking for clarification, or using gestures.

While these four competences together form the foundation of communicative ability, pragmatic competence cuts across them — connecting linguistic knowledge with real-world use. It ensures that language is not only correct and coherent but also contextually appropriate.

Table: The Four Components of Communicative Competence

| Component | Definition | Example of Use in Communication |

|---|---|---|

| Grammatical Competence | Knowledge of grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and spelling; ability to form correct sentences. | Saying “She doesn’t like coffee” instead of “She don’t like coffee.” |

| Sociolinguistic Competence | Understanding how language use varies according to context, relationship, and social norms. | Using “Could you please open the window?” instead of “Open the window!” when speaking to a teacher. |

| Discourse Competence | Ability to connect sentences and ideas coherently in spoken or written texts. | Using connectors like firstly, however, and in conclusion to organize a paragraph. |

| Strategic Competence | Using strategies to overcome communication problems or express meaning effectively. | Paraphrasing when you forget a word, e.g., saying “the thing you use to cut paper” instead of “scissors.” |

Pragmatic Competence and Its Place within Communicative Competence

While the Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) approach identifies grammatical, sociolinguistic, discourse, and strategic competences as key components, pragmatic competence brings these elements together in actual language use.

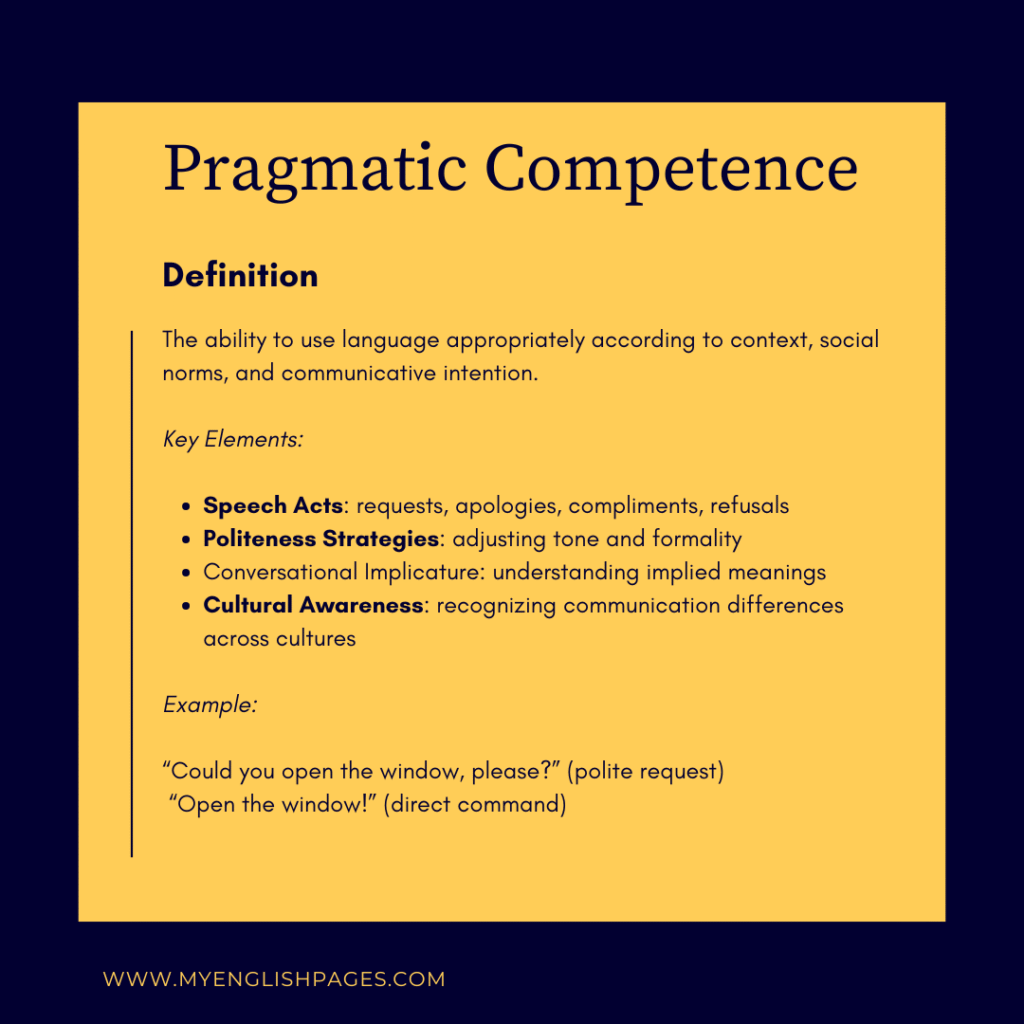

Pragmatic competence is the ability to use language appropriately according to context, social norms, and communicative intent. It ensures that utterances are not only grammatically correct and coherent but also socially suitable and culturally meaningful.

In other words, pragmatic competence operates across the four components:

- It relies on grammatical competence for accurate structures.

- It draws on sociolinguistic competence to adjust language to the situation and relationship.

- It connects to discourse competence by managing coherence and relevance.

- It uses strategic competence to repair or adapt communication when misunderstandings occur.

This integrative nature makes pragmatic competence essential for learners who aim to communicate naturally and effectively in real-world situations.

Understanding Pragmatic Competence in More Detail

As discussed earlier, pragmatic competence allows learners to use language appropriately according to context and intention. Let’s examine this concept more closely in everyday communication.

For example, English speakers might say:

- “Could you open the window, please?” (polite request)

- “Open the window!” (direct command)

Both sentences are grammatically correct, yet they differ in tone and appropriateness. Pragmatic competence helps learners choose expressions that fit the relationship between speakers and the situation.

This competence includes several key elements:

- Speech acts: requests, apologies, compliments, refusals, etc.

- Politeness strategies: showing respect or friendliness depending on social distance.

- Conversational implicature: understanding implied rather than literal meanings.

- Cultural norms: recognizing how communication styles vary across cultures.

Challenges in Developing Pragmatic Competence

Although pragmatic competence is essential for effective communication, developing it in the classroom can be quite challenging. Teachers and learners face a number of obstacles that influence how successfully this skill can be taught and acquired.

1. Limited Exposure to Authentic Input

Many language learners mainly interact with English through textbooks and classroom materials, which often prioritize grammar and vocabulary over natural, contextualized speech. As a result, learners may rarely encounter how native or proficient speakers use language to make requests, apologize, or refuse politely in real-life situations. Without sufficient exposure to authentic input, students struggle to internalize the social rules that govern communication.

2. Cultural Differences and Transfer

Pragmatic norms are deeply rooted in culture. What is considered polite, friendly, or acceptable in one language community may sound rude or strange in another. Learners often transfer the pragmatic rules of their first language into English. For instance, in some cultures, being direct is a sign of honesty, while in others it may seem impolite. Teachers must help students recognize these differences and develop cultural sensitivity in their communication.

3. Lack of Explicit Instruction

Pragmatic aspects of language are often left to be “picked up” naturally, rather than explicitly taught. However, many learners—especially those in foreign language contexts—may not have enough opportunities for immersion. Without guided practice and teacher feedback, pragmatic awareness may remain underdeveloped.

4. Fear of Making Mistakes and Limited Practice Opportunities

Because pragmatic norms are subtle and context-dependent, learners may fear making social mistakes and therefore avoid experimentation in communication. Teachers may also find it difficult to create safe classroom environments where students can freely explore how to sound polite, informal, or persuasive in English.

5. Assessment Challenges

Assessment of the development of pragmatic competence presents a unique difficulty for teachers. Unlike grammar or vocabulary, pragmatic use cannot be easily tested through traditional written exams. It requires assessing appropriateness, tone, and contextual fit, which are subjective and situation-dependent.

Some teachers rely on role-plays, self-assessment checklists, or observation during communicative tasks, but developing valid and reliable instruments for assessing pragmatic growth remains a challenge in English Language Teaching (ELT). Furthermore, students may perform well in controlled classroom situations but fail to transfer that knowledge to spontaneous real-life interactions.

→ Suggested Ways to Assess Pragmatic Development

Strategies for Developing Pragmatic Competence

Developing pragmatic competence requires both awareness and practice. The following strategies help teachers integrate these skills naturally into lessons.

1. Use Authentic Materials

Include real-life examples such as movie clips, TV shows, podcasts, or social media dialogues. These help learners observe how native speakers make requests, apologize, or give compliments naturally.

2. Encourage Reflection and Comparison

Ask students to compare how they would express something in their first language versus English. Discuss cultural and social differences that affect meaning and tone.

3. Teach Speech Acts Explicitly

Focus on specific language functions like:

- Making requests

- Giving and responding to compliments

- Refusing politely

- Apologizing or expressing gratitude

Provide models and analyze typical structures.

4. Role-Plays and Simulations

Create realistic scenarios (e.g., job interviews, restaurant situations, or complaints). Students practice appropriate expressions and tone, then discuss what worked well.

5. Provide Feedback on Pragmatic Use

During speaking activities, highlight not only grammatical errors but also pragmatic ones — for instance, when a response sounds too direct or informal for the context.

Classroom Activities to Develop Pragmatic Skills

Here are a few classroom ideas you can try:

- Dialogue Analysis: Students listen to or read dialogues and identify polite or impolite expressions.

- Discourse Completion Tasks: Give learners a situation (e.g., “Your friend arrives late to a meeting”) and ask them to write or say what they would say.

- Cultural Role Reversal: Have students act out scenes from both their own culture and an English-speaking one, discussing differences in tone and language.

- Video Observation: Watch short clips, pause, and discuss how the characters use politeness or indirectness.

Assessing Pragmatic Competence

Evaluating pragmatic competence can be challenging because it focuses not only on what learners say but also on how and when they say it. Unlike grammar or vocabulary, pragmatic ability cannot be easily measured with traditional written tests. Assessment should therefore focus on appropriateness, context, and communicative intent rather than on linguistic accuracy alone.

Below are several approaches and techniques teachers can use to assess this competence more effectively.

1. Observation during Communicative Tasks

One of the most natural ways to assess pragmatic use is through classroom observation. Teachers can evaluate how students interact during role-plays, simulations, or group discussions.

Focus on aspects such as:

- How appropriately students make requests, apologies, or refusals.

- Whether they use polite forms according to social distance.

- How they manage turn-taking and respond to others.

Teachers can use simple checklists or rating scales to note learners’ use of expressions, tone, and strategies in different situations.

2. Role-Plays and Performance-Based Assessment

Role-plays allow learners to demonstrate their pragmatic ability in contextualized scenarios such as job interviews, restaurant interactions, or complaints.

To make this assessment reliable:

- Provide clear descriptions of the situation and roles.

- Evaluate both language appropriateness and interactional strategies (e.g., softening disagreement, using modal verbs, showing empathy).

- Offer feedback on how choices of words or tone influence meaning.

This method promotes both assessment and learning, since students can reflect on and adjust their performance afterward.

3. Discourse Completion Tasks (DCTs)

A Discourse Completion Task presents learners with a situation and asks them to write or say how they would respond.

Example:

Your colleague helped you finish a report yesterday. What would you say to show your gratitude?

Responses can then be analyzed for appropriateness, tone, and cultural fit. DCTs are useful for comparing learners’ understanding of social norms across contexts (e.g., formal vs. informal).

4. Self-Assessment and Reflection

Encouraging students to assess their own pragmatic performance helps build awareness and autonomy.

You can design short reflection checklists or questions such as:

- Did I choose expressions suitable for the situation?

- Was my tone polite or too direct?

- How would a native speaker respond in this context?

Self-assessment fosters metapragmatic awareness — the ability to think about language use consciously.

5. Peer Feedback and Collaborative Evaluation

In pair or group work, peers can observe and provide feedback on each other’s communication. This collaborative approach exposes students to multiple interaction styles and promotes discussion about what sounds natural or polite in English.

6. Situational Judgment Tests (SJTs)

Situational Judgment Tests present learners with short dialogues or scenarios and ask them to choose the most appropriate response among several options.

For example:

You accidentally interrupt someone in a meeting. What should you say?

a) “Keep talking.”

b) “Sorry for interrupting, please continue.”

c) “Why are you taking so long?”

SJTs can be useful in both formative and summative assessments, offering a more controlled way to evaluate pragmatic understanding.

→ More about Communicative Tests and Activities

7. Portfolios and Long-Term Assessment

Because pragmatic development takes time, teachers can encourage students to keep learning portfolios that include samples of recorded dialogues, reflections, and written responses to pragmatic tasks.

Over time, this provides a rich picture of the learner’s progress in using English appropriately in various situations.

In summary

Effective assessment of pragmatic competence should combine observation, reflection, and performance-based tasks. It is not about testing perfect English, but about understanding how well learners adapt their language to express meaning appropriately in different contexts. When teachers integrate such assessment practices, they not only measure progress but also promote genuine communicative ability.

FAQs about Pragmatic Skills in English Language Teaching

What is pragmatic competence?

Pragmatic competence is the ability to use language appropriately in different social and cultural contexts. It involves knowing what to say, how to say it, when to say it, and to whom. Learners with strong pragmatic competence can adjust their language according to relationships, intentions, and situations — for example, using polite requests (“Could you please…?”) instead of direct commands (“Do it now!”) when speaking to someone of higher status.

What does pragmatic development mean?

Pragmatic development refers to the process through which language learners acquire the ability to use language appropriately and effectively in communication. It involves learning how to perform speech acts (like apologizing or refusing), understanding politeness norms, and interpreting implied meanings. Pragmatic development occurs gradually as learners gain more exposure to authentic input, receive feedback, and reflect on their language use.

Can pragmatic competence be taught?

Yes, pragmatic competence can and should be taught. While some learners develop it naturally through interaction, many benefit from explicit instruction and guided practice. Teachers can promote pragmatic awareness through authentic materials (films, real conversations), role-plays, and reflection activities. Explicit feedback on tone, politeness, and appropriateness also helps learners refine their communicative choices.

What are the 4 types of communicative competence?

According to Canale and Swain (1980), communicative competence consists of four key components:

– Grammatical competence – knowledge of syntax, vocabulary, and pronunciation.

– Sociolinguistic competence – understanding how to use language appropriately depending on the context or relationship.

– Discourse competence – ability to connect sentences and ideas to create coherent speech or writing.

– Strategic competence – use of communication strategies to overcome problems or clarify meaning.

Pragmatic competence draws on all these areas, ensuring that communication is not only correct but also contextually appropriate.

Why is pragmatic competence important in English language teaching?

Pragmatic competence is vital because it helps learners communicate naturally and effectively in real-world situations. Even when their grammar is perfect, learners can still misunderstand or sound impolite if they lack pragmatic awareness. Teaching this competence prepares students to use English in culturally appropriate ways — a key goal of communicative language teaching (CLT).

How can teachers assess pragmatic competence?

Teachers can assess pragmatic competence through role-plays, discourse completion tasks, self-assessment checklists, and situational judgment tests. Observation during communicative activities and reflective portfolios are also useful. The focus should be on the appropriateness and effectiveness of the learner’s responses rather than grammatical perfection.

Conclusion

Developing pragmatic competence helps learners go beyond linguistic accuracy to achieve real communicative effectiveness.

By integrating authentic materials, explicit teaching, and reflective practice, teachers can help students use English in culturally and socially appropriate ways. After all, knowing what to say is just as important as knowing how to say it.

For more insights into how pragmatics shapes classroom communication, see this article on Pragmatics in Language Teaching

Related Pages

- What Is Linguistics? A Comprehensive Guide

- Why study linguistics?

- What Is Applied Linguistics?

- English Discourse Analysis: Meaning, Types, Examples, and Teaching Applications

- Second Language Acquisition Theories (Explained with Examples)

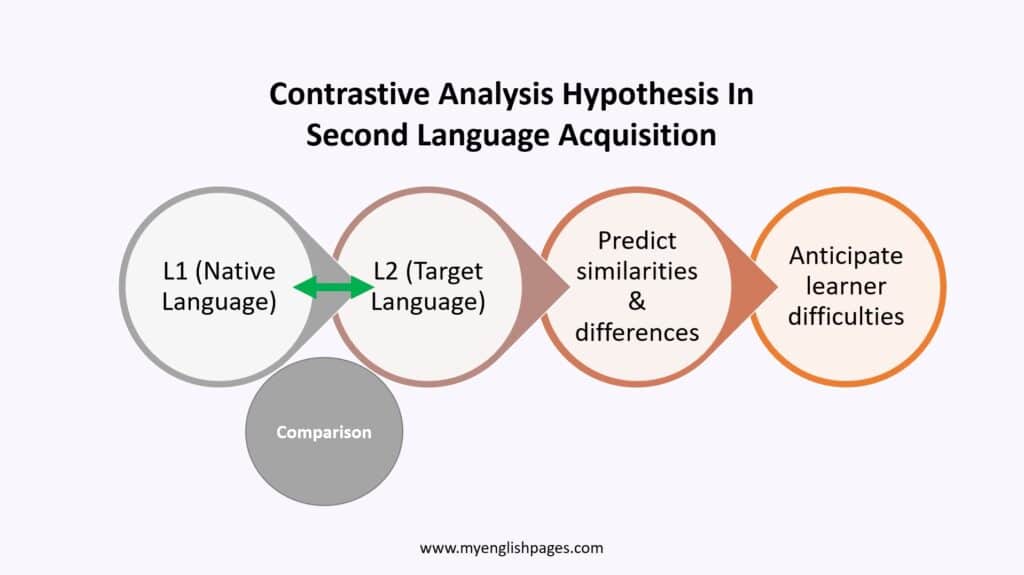

- Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis in Second Language Acquisition

- Communicative Activities

- Communicative Tests

FANBOYS Conjunctions Quiz (20 Multiple Choice Questions) 23 Oct 3:18 AM (7 days ago)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Are you ready to test your knowledge of FANBOYS conjunctions?

FANBOYS stands for For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, So — the seven coordinating conjunctions used to join words, phrases, and clauses.

This FANBOYS conjunctions quiz will help you practice connecting ideas correctly in English. Choose the correct coordinating conjunction in each sentence.

FANBOYS Conjunctions Quiz with Answers

"FANBOYS Conjunctions"!

Test your knowledge of the FANBOYS Conjunctions with this quiz.

-

Read each question carefully.

-

Choose the best answer from the four options provided.

Example:

She likes coffee ___ tea

- a) yet

- b) and ✅

- c) or

- d) but

Time's up

Quick Review of FANBOYS Conjunctions

How did you do on this FANBOYS conjunctions quiz? If you got most of the answers right, great job! If not, review the meanings of each coordinating conjunction:

- For – shows reason

- And – adds ideas

- Nor – gives a negative alternative

- But – shows contrast

- Or – gives choice

- Yet – shows unexpected contrast

- So – shows result

Related Pages

👉 Try our related quiz: Conjunctions (and, but, or) or explore our Grammar Quizzes section for more practice.

You may also be interested in:

- FANBOYS Conjunctions

- What Are Conjunctions In English?

- Conjunctions and Subordinating Conjunctions

- Grammar Exercise: Conjunctions In English

English Discourse Analysis: Meaning, Types, Examples, and Teaching Applications 20 Oct 3:33 AM (10 days ago)

Table of Contents

Introduction

In English language teaching, understanding how people use language in real communication is just as important as mastering grammar and vocabulary. Discourse analysis (DA) helps teachers and learners explore how sentences, words, and structures come together to create meaning in real contexts.

This article provides a comprehensive guide to discourse analysis for teachers, including key concepts, types, classroom applications, and practical activities. By integrating DA into lessons, teachers can help learners become more effective, confident, and contextually aware communicators.

What Is English Discourse Analysis?

Discourse analysis is the study of how language is used in real-life communication — in conversations, essays, news articles, advertisements, emails, and classroom interactions. It goes beyond the sentence level to explore how meaning is constructed through context, social interaction, and purpose.

Instead of focusing only on grammar and vocabulary, discourse analysis investigates how ideas are organized, how cohesion and coherence are achieved, and how speakers and writers use language strategically to inform, persuade, question, or connect with others.

Unlike traditional grammar study, DA focuses on:

- How ideas are organized and linked.

- How coherence and cohesion are achieved.

- How speakers and writers shape meaning in context.

At its core, discourse analysis views language as a social action — something people do rather than simply a system of rules they know. Every utterance depends on the situation in which it occurs: who is speaking or writing, to whom, about what, and for what reason. This means that language can only be fully understood when studied in its context of use.

The field draws on insights from linguistics, sociolinguistics, pragmatics, semiotics, and communication studies. It examines both the structure of texts (their cohesion, organization, and grammar) and their function (how they achieve communicative and social purposes).

💡 Note: The word discourse refers to language in use — stretches of spoken or written communication that go beyond individual sentences. A discourse can be a short exchange between two people, a political speech, an academic article, or even a social media post. What matters is how language functions to express ideas and achieve specific purposes in context.

Key Concepts: Discourse Analysis Basics

Key Concepts: Discourse Analysis Basics

Discourse analysis examines not only words and sentences but also how meaning is constructed in context. Key concepts include:

1. Cohesion

Cohesion refers to grammatical and lexical links connecting sentences and ideas. Devices include:

- Pronouns and references (he, she, it, this, that)

- Conjunctions and linking words (and, but, therefore)

- Lexical repetition and synonyms

- Substitution and ellipsis

Classroom Tip: Have students highlight cohesive devices in texts or rewrite paragraphs using alternative connectors.

2. Coherence

Coherence is the logical and meaningful organization of ideas, helping texts make sense as a whole. Teachers can guide students in:

- Logical sequencing (cause-effect, comparison)

- Clear paragraphing and topic development

- Maintaining relevance to the main idea

3. Context

Context shapes how messages are produced and interpreted. Key aspects:

- Physical context: Where communication happens (classroom, office, online)

- Social context: Roles and relationships of participants

- Cultural context: Shared norms and expectations

Classroom Tip: Role-plays help learners adapt language for formal vs. informal situations.

4. Speech Acts

Speech acts are the functions of language, such as requesting, apologizing, promising, greeting, or complaining.

Classroom Tip: Practice dialogues to perform different speech acts in authentic scenarios.

5. Turn-Taking and Interaction

Turn-taking involves managing who speaks, when, and how, including:

- Pauses, overlaps, and interruptions

- Topic shifts and continuation

- Repair strategies for misunderstandings

Classroom Tip: Record short class discussions and analyze turn-taking and conversational strategies.

6. Genre and Register

- Genre: Conventional structure of a text type (letters, reports, emails, narratives)

- Register: Level of formality and style (formal vs. informal, technical vs. everyday)

Classroom Tip: Compare texts across genres and registers to explore differences in tone, vocabulary, and structure.

7. Power and Ideology

Examines how language reflects or challenges social hierarchies, stereotypes, or cultural beliefs. CDA focuses on:

- Word choice and framing

- Representation of gender, ethnicity, or social class

- Persuasive strategies and social influence

Classroom Tip: Analyze media, advertisements, or political texts to discuss bias and social power.

Key Discourse Analysis Concepts and Their Practical Classroom Activities:

| Key Concept | Explanation | Classroom Activity / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cohesion | Grammatical and lexical links that connect sentences (pronouns, conjunctions, repetition, substitution). | Have students highlight cohesive devices in a text or rewrite a paragraph using different cohesive words. |

| Coherence | Logical and meaningful flow of ideas; overall clarity of a text. | Ask students to reorder jumbled sentences into a coherent paragraph or outline main ideas from a text. |

| Context | Situational, social, and cultural circumstances influencing meaning. | Role-play activities: students adapt language for formal vs. informal situations or different audiences. |

| Speech Acts | Functions of language: requesting, apologizing, promising, greeting, complaining, etc. | Practice dialogues where students perform different speech acts or identify them in authentic conversations. |

| Turn-Taking & Interaction | How speakers manage conversation: speaking order, overlaps, repairs, topic shifts. | Record and analyze short class discussions; discuss pauses, interruptions, and turn-taking strategies. |

| Genre & Register | Conventional structures of text types and level of formality. | Compare emails vs. letters, news articles vs. blog posts; discuss tone, vocabulary, and structure. |

| Power & Ideology | How language reflects, constructs, or challenges social hierarchies and beliefs. | Critical reading tasks: analyze media, advertisements, or political texts to identify bias or hidden assumptions. |

Origins and Key Thinkers

Discourse analysis has its roots in linguistics, sociology, and anthropology, and its development has been shaped by scholars interested in how language functions in social contexts. In applied linguistics, several key thinkers have made foundational contributions:

1. M.A.K. Halliday

Halliday introduced the concept of language as a social semiotic, highlighting that meaning is not just grammatical but also functional. He emphasized that language is shaped by context and serves different purposes, such as conveying information, building relationships, or expressing personal identity. His Systemic Functional Linguistics framework helps teachers analyze texts for patterns of meaning, choices of vocabulary, and the functions of different clauses.

2. Norman Fairclough

Fairclough is a central figure in Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), which examines how language both reflects and perpetuates social power, ideologies, and inequalities. His work is particularly relevant in the classroom for discussions about media bias, persuasive texts, or societal representations of gender, race, and class. CDA encourages students to see beyond surface meanings and question the social implications of language.

3. James Paul Gee

Gee focused on Discourse with a capital “D,” defining it as language intertwined with social practices, identities, and ways of being. He explored how language shapes and is shaped by social groups and communities. For teachers, this perspective can illuminate how students’ backgrounds, identities, and community norms influence their language use and learning.

4. Teun A. van Dijk

Van Dijk developed frameworks for analyzing discourse structures and ideology, often combining linguistic analysis with social and cognitive perspectives. His work highlights how texts can subtly influence perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs, making it valuable for critical reading and media literacy activities.

While these approaches differ in focus and methodology, they share a common understanding: language is not neutral—it is deeply connected to social interaction, culture, and power. For teachers, this insight provides a rich foundation for exploring how students use language, interpret texts, and engage in meaningful communication.

Why Discourse Analysis Matters in English Teaching

For EFL and ESL teachers, discourse analysis offers valuable insights into language learning and use. It can help you:

- Improve learners’ coherence and cohesion in writing and speaking.

- Analyze classroom interaction to promote better participation and communication strategies.

- Develop materials that reflect authentic language use.

- Enhance students’ critical awareness of how language conveys social and cultural meanings.

When students understand how discourse works, they can become more effective communicators — not just grammatically correct, but contextually appropriate and persuasive.

How Discourse Analysts Work: Typical Procedures

Discourse analysis is usually conducted through a systematic process. While approaches differ depending on the type (descriptive, conversational, pragmatic, or critical), most analysts follow these steps:

- Defining the Research Question or Goal

Analysts start by identifying what they want to study: a conversation, a written text, classroom interaction, or media discourse. In teaching, this could translate into focusing on how students structure essays, manage dialogue, or interpret persuasive texts. - Selecting Data

The next step is choosing the material to analyze. This could be transcripts of spoken interaction, written texts, emails, or authentic classroom recordings. For teachers, authentic materials or learner-produced texts often work best. - Transcribing and Segmenting

For spoken discourse, conversations are often transcribed, noting pauses, intonation, overlaps, and nonverbal cues. Texts are segmented into sentences, clauses, or meaningful units. This allows for detailed examination of language patterns. - Analyzing Linguistic Features

Analysts examine cohesion, coherence, sentence structure, vocabulary choice, and use of discourse markers. They also look at how context, register, and genre influence meaning. In the classroom, this step can involve identifying key connectors, repetition, or paragraph organization. - Interpreting Meaning and Function

This step focuses on how language conveys meaning, achieves communicative goals, or reflects social relationships. For example, analysts might explore how politeness strategies or persuasive techniques operate in a text. - Considering Social and Cultural Context

Analysts, especially in CDA, examine how power, ideology, and social norms shape language. Teachers can adapt this by discussing media bias, representation, or cultural expectations in texts. - Reporting Findings

Finally, the results are summarized and interpreted. In teaching, this might involve sharing patterns with students, designing activities to reinforce cohesion and coherence, or fostering critical awareness of language use.

Main Types of Discourse Analysis

There are several approaches to discourse analysis, each offering different insights into how language functions in context. For teachers, understanding these approaches can help design lessons that connect grammar, vocabulary, and communication skills in meaningful ways.

1. Descriptive Discourse Analysis

Descriptive discourse analysis focuses on how texts are organized — how sentences connect, how ideas flow, and how cohesion and coherence are achieved.

Teachers can use this approach to help learners see beyond individual sentences and understand how writers and speakers create meaningful, connected messages.

Key features include:

- Use of cohesive devices (such as however, therefore, in addition).

- Reference chains (using pronouns or synonyms to refer back to earlier ideas).

- Lexical repetition and thematic progression (how key words and topics are developed).

In the classroom:

- Teachers can guide students to analyze short paragraphs, identifying linking words, topic sentences, and transitions. This helps learners improve both reading comprehension and writing organization.

Example activity:

- Provide a jumbled paragraph and ask students to reorder the sentences using cohesive clues (e.g., Firstly, as a result, in contrast).

2. Conversational Analysis

Conversational analysis (CA) examines the structure and flow of spoken interaction. It looks at how people manage turn-taking, pauses, interruptions, and repair strategies (how speakers correct themselves or others).

This approach reveals how real communication works beyond the textbook dialogues.

Key features include:

- Turn-taking rules (who speaks when and how transitions happen).

- Overlaps and interruptions — when two people talk at once and how they resolve it.

- Politeness strategies and backchanneling (e.g., yeah, uh-huh, I see).

In the classroom:

- CA is particularly useful for teaching speaking and listening skills. By analyzing authentic conversations or recordings, learners notice how speakers negotiate meaning and maintain interaction.

Example activity:

- Play a short dialogue and ask students to identify signs of agreement, hesitation, or politeness. Discuss how these choices affect the tone of the conversation.

3. Pragmatic Analysis

Pragmatic discourse analysis studies how meaning is influenced by context, intention, and shared knowledge. It focuses on what speakers mean rather than just what they say.

This approach helps learners understand indirect language, implicature, irony, and speech acts (like requesting, apologizing, or suggesting).

Key features include:

- Contextual meaning: how situation, tone, and relationship affect interpretation.

- Speech acts: identifying the function of utterances (e.g., “Could you open the window?” = request).

- Cultural awareness: understanding politeness and formality across cultures.

In the classroom:

- Teachers can use pragmatic analysis to build communicative competence — helping learners choose appropriate language for different situations.

Example activity:

- Present several indirect requests (e.g., It’s a bit cold in here). Ask students to interpret what the speaker really wants and to create similar expressions for different contexts.

4. Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA)

Critical Discourse Analysis explores how language reflects and reinforces power relations, ideologies, and social inequality. It encourages both teachers and students to become critical readers and listeners, questioning how meaning is constructed in media, politics, and everyday discourse.

Key features include:

- How word choice, framing, and tone influence perception in a language.

- How texts represent gender, ethnicity, or social class.

- How language maintains or challenges power structures.

In the classroom:

- Teachers can integrate CDA into reading or media literacy lessons. Students learn to identify bias, stereotypes, and hidden assumptions in texts, advertisements, or news reports.

Example activity:

- Compare two news headlines about the same event and discuss how wording shapes interpretation (e.g., “Protesters Clash with Police” vs. “Citizens Demand Justice”).

Summary Table: Types of Discourse Analysis for Teachers

| Type of Discourse Analysis | Main Focus | Key Concepts | Classroom Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive Discourse Analysis | Structure and organization of texts | Cohesion, coherence, reference, lexical repetition | Analyzing how sentences connect in reading and writing; identifying cohesive devices |

| Conversational Analysis (CA) | Patterns of spoken interaction | Turn-taking, pauses, overlaps, politeness, repair strategies | Teaching natural conversation, listening skills, and pragmatic speaking strategies |

| Pragmatic Analysis | Contextual meaning and intention | Speech acts, implicature, cultural norms, politeness | Developing communicative competence and understanding indirect or implied meaning |

| Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) | Power, ideology, and social meaning in language | Bias, representation, framing, ideology | Encouraging critical reading and media literacy; analyzing social messages in texts |

Features of English Discourse

Discourse analysis often examines several linguistic and functional features that shape how meaning is conveyed in communication. Understanding these features can help teachers guide learners to produce more natural, coherent, and purposeful language.

1. Cohesion

Cohesion refers to the explicit links between sentences and parts of a text that make it hang together. It involves the use of linguistic devices such as:

- Conjunctions: Words like and, but, although that connect ideas.

- Reference: Pronouns or demonstratives (he, she, it, this, that) that refer back to previous elements.

- Substitution and ellipsis: Replacing words or omitting repeated information for fluency.

- Lexical cohesion: Repetition, synonyms, and related vocabulary that reinforce meaning.

By teaching cohesion, educators can help learners write and speak more smoothly, avoiding abrupt or disjointed language.

2. Coherence

Coherence is the logical flow of ideas in a text — how well the content makes sense as a whole. It depends not only on cohesion but also on:

- Clear organization of ideas (introduction, development, conclusion).

- Logical sequencing (cause-effect, comparison, problem-solution).

- Consistency in topic and perspective.

Helping students understand coherence enables them to structure essays, reports, and oral presentations in ways that are easier for their audience to follow.

3. Context

Context includes the situation in which communication occurs, the participants involved, and the communicative purpose. Important aspects include:

- Situational context: Where, when, and under what circumstances communication takes place.

- Social context: Relationship between speakers, power dynamics, and cultural norms.

- Purpose: Informing, persuading, requesting, narrating, or entertaining.

Teaching students to consider context helps them choose appropriate language, tone, and style for different situations.

4. Turn-taking

In spoken interaction, turn-taking governs how speakers share the conversation. Key points include:

- Signals for starting and ending turns.

- Pauses, overlaps, and interruptions.

- Strategies for politely gaining attention or yielding the floor.

Understanding turn-taking is crucial for teaching speaking and listening skills, particularly in group discussions, debates, or role-plays.

5. Register and Genre

Register refers to the level of formality and style, while genre refers to the type of text or discourse. Examples include:

- Register: Formal (academic essay) vs. informal (chat, personal email).

- Genre: Narrative, descriptive, argumentative, instructional, or conversational.

By recognizing register and genre, teachers can guide students to adapt their language to different communicative contexts, enhancing both comprehension and production skills.

Examples of Discourse Analysis

To illustrate how discourse analysis works, consider these examples:

- In a conversation:

Teachers can analyze how learners use backchanneling (e.g., uh-huh, I see) or how they take turns to maintain interaction. - In a written text:

Students can study how paragraphs develop a topic and how linking words like however, therefore, or in addition create logical flow. - In classroom discourse:

A teacher might record a lesson and analyze patterns such as Initiation–Response–Feedback (IRF) to improve interactional balance.

Applying Discourse Analysis in the Classroom

Discourse analysis offers a wealth of practical applications for English teaching. By focusing on how language works in real contexts, teachers can help learners develop stronger comprehension, production, and interaction skills. Here are some ways to apply discourse analysis in lessons:

1. Text Analysis Tasks

Students can examine authentic texts—articles, essays, emails, or short stories—to identify linguistic features such as:

- Cohesive devices: Conjunctions, pronouns, reference chains, substitution, ellipsis, and lexical repetition.

- Paragraph structure: Topic sentences, supporting details, and concluding statements.

- Coherence strategies: Logical sequencing of ideas and clarity of argument.

These activities help learners notice how writers organize ideas, link sentences, and create meaning beyond individual words or grammar points.

2. Genre Comparison

Comparing texts of different types or genres allows students to explore variations in language use and communicative purpose. Examples include:

- News article vs. blog post

- Formal letter vs. email

- Instructional text vs. narrative story

Teachers can guide learners to examine differences in tone, vocabulary, structure, and level of formality, encouraging awareness of how language choices relate to audience and purpose.

3. Conversation Practice

Analyzing spoken interaction gives learners insight into how real communication works. Activities might include:

- Recording short dialogues or role-plays and reviewing them to identify turn-taking, pauses, overlaps, and repair strategies.

- Discussing politeness strategies, indirect requests, and conversational markers such as well, actually, you know.

- Practicing strategies for clarification, interruption, or signaling disagreement in socially appropriate ways.

This approach strengthens learners’ speaking and listening skills while raising awareness of pragmatics and social norms in English.

4. Critical Reading Activities

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) can be incorporated to help learners question and interpret texts beyond their surface meaning. Tasks may include:

- Identifying bias, stereotypes, or persuasive techniques in advertisements, news articles, or political speeches.

- Discussing how language reflects social power, ideology, and cultural assumptions.

- Encouraging reflection on one’s own responses to texts and how interpretation is shaped by context.

These activities foster critical thinking and media literacy, preparing learners to navigate real-world texts thoughtfully.

5. Integrated Writing and Speaking Tasks

Teachers can combine discourse analysis with productive skills:

- Have students write a text (essay, dialogue, or email) and then analyze their own use of cohesion, coherence, and register.

- Conduct peer review sessions, where students identify discourse features in classmates’ writing or speaking and suggest improvements.

- Use reflective discussions on how language choices affect meaning, tone, or persuasiveness.

By integrating discourse analysis into classroom tasks, learners not only improve their English skills but also develop metalinguistic awareness, helping them become more autonomous and confident users of the language.

Challenges of Using Discourse Analysis Findings in Language Teaching

While discourse analysis (DA) offers valuable insights into how language works in real contexts, applying its findings in the classroom comes with some challenges. Teachers need to be aware of these potential obstacles to design effective, practical activities.

Some common challenges include:

- Time and training requirements: Conducting discourse analysis and interpreting its results can be time-consuming and may require specialized knowledge. Teachers need some training to apply DA concepts effectively.

- Abstract concepts: Ideas like ideology, power relations, or social context can be difficult for learners to grasp, especially in younger or lower-level classes.

- Complex authentic materials: Real-world texts and conversations often contain cultural references, idiomatic expressions, and complex structures that can be challenging for students to analyze.

Despite these challenges, discourse analysis can be highly rewarding. By carefully adapting tasks, setting clear objectives, and scaffolding activities, teachers can make DA accessible and engaging.

DA is particularly valuable for understanding how language users interact, negotiate meaning, and construct messages in different contexts. Integrating discourse-based insights into teaching can help learners develop more natural, purposeful, and contextually appropriate language skills.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Discourse Analysis

Discourse analysis offers valuable insights for understanding language in context, but like any approach, it has its advantages and limitations.

Strengths

- Focus on real language use – Unlike approaches that analyze isolated sentences, discourse analysis examines how language functions in actual communication, making it highly relevant for teaching speaking, writing, and comprehension.

- Enhances understanding of meaning – It helps teachers and learners explore how ideas are structured, how coherence and cohesion are achieved, and how tone, politeness, and intention affect interpretation.

- Supports communicative teaching – By analyzing classroom interactions, teacher talk, and student responses, educators can design activities that improve authentic communication skills.

- Encourages critical thinking – Critical discourse analysis, in particular, allows learners to examine how language reflects social power, ideology, and cultural assumptions.

- Flexible and multidisciplinary – Discourse analysis draws from linguistics, sociology, pragmatics, and anthropology, offering multiple perspectives for analyzing texts and conversations.

Weaknesses

- Time-consuming – Detailed discourse analysis, especially of long texts or interactions, requires careful observation and annotation, which can be challenging in classroom settings.

- Subjectivity – Interpreting meaning, intention, or social context can be influenced by the analyst’s perspective, potentially affecting reliability.

- Complexity – Some methods, like critical discourse analysis, involve advanced theoretical frameworks that may be difficult for beginners to apply effectively.

- Limited generalizability – Findings from analyzing specific texts or classroom interactions may not always apply to other contexts or learners.

- Requires training – Teachers may need additional professional development to effectively integrate discourse analysis into lesson planning or material design.

Conclusion

English discourse analysis bridges theory and practice. For teachers, it provides a framework to understand how communication really works — how grammar, vocabulary, and context combine to express meaning. When integrated into classroom practice, it helps learners become thoughtful, confident, and effective communicators in English.

Frequently Asked Questions About English Discourse Analysis

Is discourse analysis a theory?

Discourse analysis is not a single theory; rather, it is a broad field of study that encompasses multiple approaches and frameworks for examining language in use. It draws on insights from linguistics, sociology, anthropology, and communication studies. Different types of discourse analysis (e.g., conversational analysis, critical discourse analysis, pragmatic analysis) are informed by different theories, but the overarching goal is to understand how language functions in context.

What are the four types of discourse analysis?

– Descriptive discourse analysis – describes patterns of language use.

– Critical discourse analysis (CDA) – explores power and ideology.

– Conversational analysis – studies spoken interaction.

– Pragmatic analysis – examines meaning in context.

What are examples of discourse analysis?

Examples include studying teacher–student talk, analyzing news headlines, exploring political speeches, or examining essay organization and cohesion.

What are the key features of CDA (Critical Discourse Analysis)?

CDA focuses on how language expresses power, ideology, and inequality. It considers social and historical context, aims to uncover bias, and encourages critical awareness.

What are the five categories of discourse analysis?

– Narrative discourse – storytelling.

– Descriptive discourse – describing things or people.

– Expository discourse – explaining ideas.

– Argumentative discourse – persuading or debating.

– Conversational discourse – everyday spoken language.

Related Pages

- What Is Linguistics? A Comprehensive Guide

- Why study linguistics?

- What Is Applied Linguistics? 9 Examples That Define, Inspire And Unleash the Power of Applied Linguistics

- Learning and Learning Theories

100 Examples of Simple Past Tense Sentences 18 Oct 4:43 AM (12 days ago)

Table of Contents

What Is the Simple Past Tense?

The simple past tense (also called the past simple or preterite) is used to describe completed actions or events that happened in the past.

Examples:

- She watched a movie yesterday.

- They traveled to London last summer.

- He didn’t go to school yesterday.

In this lesson, you will find 100 examples of simple past tense sentences — including regular and irregular verbs, as well as affirmative, negative, and interrogative forms.

How to Form the Simple Past Tense

Regular Verbs

Add –ed to the base form of the verb.

play → played

visit → visited

work → worked

Irregular Verbs

Change the verb form completely.

go → went

see → saw

eat → ate

Negatives and Questions

Use the auxiliary verb did:

- Negative → did not (didn’t) + base verb

- Question → Did + subject + base verb?

Examples of Simple Past Tense – Regular Verbs

- I watched a movie last night.

- She played tennis with her friends.

- We visited the museum on Sunday.

- They worked hard all week.

- He cleaned his room yesterday.

- I cooked dinner for my family.

- She walked to school this morning.

- We painted the walls last weekend.

- He washed the car on Saturday.

- They opened their gifts eagerly.

- I helped my brother with his homework.

- She listened to her favorite song.

- We studied for the English exam.

- He called his friend yesterday.

- They waited for the bus in the rain.

- I finished reading that novel.

- She danced beautifully at the party.

- We watched the football match together.

- He visited his grandparents last summer.

- They enjoyed their trip to Spain.

Examples of Simple Past Tense – Irregular Verbs

- I went to the supermarket.

- She saw a shooting star.

- We ate pizza for dinner.

- They came home late.

- He drank orange juice this morning.

- I bought a new book yesterday.

- She took many photos at the beach.

- We met our teacher at the library.

- He wrote a message to his friend.

- They ran in the park after school.

- I gave him a birthday present.

- She spoke to her parents about it.

- We built a sandcastle on the beach.

- He found a coin on the ground.

- They flew to Paris last year.

- I read an interesting article.

- She broke her phone by accident.

- We sang our favorite song.

- He drove to work this morning.

- They chose the red dress.

Negative Sentences in the Simple Past

- I didn’t watch TV yesterday.

- She didn’t visit her aunt.

- We didn’t eat breakfast today.

- They didn’t play football.

- He didn’t study for the exam.

- I didn’t go to the party.

- She didn’t call me back.

- We didn’t open the window.

- He didn’t like the food.

- They didn’t finish their project.

- I didn’t meet my friends.

- She didn’t drive to work.

- We didn’t have time to rest.

- He didn’t take his medicine.

- They didn’t read the instructions.

- I didn’t sleep well last night.

- She didn’t speak loudly.

- We didn’t buy any gifts.

- He didn’t come to school.

- They didn’t clean their room.

Questions in the Simple Past

- Did you watch the movie last night?

- Did she finish her homework?

- Did they visit London last year?

- Did he play the guitar?

- Did you see that new restaurant?

- Did we win the game?

- Did she write the report?

- Did he drive to the office?

- Did they go swimming?

- Did you eat breakfast?

- Did she call her mother?

- Did we study enough?

- Did he come on time?

- Did they speak to the teacher?

- Did you take your umbrella?

- Did she dance at the wedding?

- Did we travel by train?

- Did he tell the truth?

- Did you buy any food?

- Did they enjoy the concert?

Mixed Examples of Regular and Irregular Verbs

- I lived in Paris for two years.

- She drove to the mountains.

- We talked about our childhood.

- They built a new house last year.

- He watched the sunrise from the hill.

- I met her at the café.

- She studied all night.

- We went for a walk after dinner.

- He played the piano beautifully.

- They saw a rainbow after the storm.

- I cooked pasta for lunch.

- She wrote a letter to her cousin.

- We painted the living room blue.

- He took photos during the trip.

- They visited their grandparents yesterday.

- I read that book last month.

- She cleaned the kitchen this morning.

- We drank coffee together.

- He watched a funny video online.

- They went to the zoo on Sunday.

Summary of Simple Past Rules

| Type | Rule | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Regular verbs | Add –ed | play → played |

| Irregular verbs | Change verb form | go → went |

| Negative | didn’t + base verb | didn’t play |

| Question | Did + subject + base verb | Did you play? |

Related Lessons

- Simple Past Exercises

- Past Tense of “To Be”

- Past Continuous vs Simple Past Quiz

- Simple Present Vs Simple Past Quiz

- Past Perfect Vs Simple Past Exercises With Answers

- Review of English Tenses

- Examples of English Tenses

- List of Irregular Verbs

💡 Final Tip

Practice is the best way to master verb tenses!

Try writing your own sentences in the simple past using both regular and irregular verbs, then check them with the examples above.

More information about the past simple tense!

Advanced Grammar Concepts: Master Complex English Structures 17 Oct 7:16 AM (13 days ago)

Table of Contents

Introduction to Advanced Grammar Concepts

Mastering advanced English grammar is essential for learners who want to communicate fluently and accurately. While basic grammar lays the foundation, advanced grammar concepts help you write and speak with clarity, professionalism, and style.

This guide covers complex sentence structures, advanced verb forms, cohesion strategies, and common mistakes, giving you the tools to elevate your English skills.

Jump to: Full List of Advanced Grammar Lessons

Understanding Complex Sentence Structures in English

Advanced learners often need to use complex sentence structures to express nuanced ideas, connect multiple thoughts, and create more sophisticated writing. Mastering these structures is essential for academic English, professional writing, and fluent communication.

1. Inversion

Inversion occurs when the usual word order is reversed, often for emphasis or style.

Example:

- Rarely have I seen such talent.

- Never did she expect to win the award.

2. Cleft Sentences

Cleft sentences are used to emphasize a particular part of a sentence, usually the subject or object.

Example:

- It was the teacher who explained the concept clearly.

- What I need is a quiet place to study.

3. Clauses

Clauses are groups of words that contain a subject and a verb. Understanding different types is key to complex sentences:

- Independent Clause: Can stand alone as a sentence.

- She loves reading novels.

- Dependent/Subordinate Clause: Cannot stand alone and depends on an independent clause.

- Although she was tired, she finished her homework.

4. Nominal Clauses

Nominal clauses function as a noun in a sentence and often begin with that, what, how, or whether.

Example:

- What he said surprised everyone.

- That she passed the exam was a relief to her family.

5. Complex Sentences

A complex sentence combines an independent clause with one or more dependent clauses.

Example:

- I stayed home because it was raining.

- Although he was tired, he continued working on the project.

6. Compound-Complex Sentences

These compound-complex sentences combine multiple independent clauses with at least one dependent clause.

Example:

- I wanted to go for a walk, but it started raining, so I stayed home.

- She studied hard for the exam because she wanted to succeed, and her friends supported her.

7. Conditional Sentences (If Clauses)

Conditional sentences express cause-and-effect or hypothetical situations.

Real Conditionals (possible situations):

- If it rains, we will cancel the picnic.

- If you study hard, you pass the test.

Unreal Conditionals (hypothetical or impossible situations):

- If she had known about the meeting, she would have attended.

- If I were taller, I would play basketball.

Mastering Advanced Verb Forms

Verbs are the backbone of advanced grammar. Focus on mastering:

- Perfect Tenses: I have been studying English for five years.

- Infinitives and Gerunds: “I agreed to help her” vs. “I think of offering help to her.”

- Causatives: She had her car repaired.

- Subjunctive Mood: I suggest that he study harder.

- Conditionals and Modals: Expressing hypothetical situations and nuanced meanings.

Practicing these advanced English grammar rules ensures accuracy and flexibility in speaking and writing.

Improving Cohesion and Coherence in Writing

Advanced writing isn’t just about grammar—it’s about connecting ideas clearly. Effective techniques include:

- Linkers: however, therefore, moreover

- Reference Words: this, that, these, those

- Parallelism: She likes reading, writing, and painting.

These tools help your sentences and paragraphs flow logically, improving overall clarity and cohesion in English.

Nominalization and Formal English Style

Nominalization turns verbs or adjectives into nouns, creating a more formal and academic tone:

- The committee will investigate → The investigation will be conducted.

- Strong → Strength

Mastering this technique is essential for academic English grammar and professional writing.

Common Mistakes in Advanced English Grammar

Even advanced learners make errors. Watch out for:

- Overusing complex sentences can make writing heavy.

- Confusing perfect tenses and conditional sentences.

- Forgetting subject-verb agreement in long sentences.

- Mixing formal and informal writing styles.

Avoiding these mistakes improves readability and demonstrates mastery of advanced grammar concepts.

FAQs About Advanced Grammar Concepts

What are advanced grammars?

Advanced grammar refers to higher-level English concepts, including complex sentence structures, nuanced verb forms, formal writing techniques, and cohesion strategies that go beyond basic rules.

What is the hardest topic in grammar?

Many learners struggle with advanced tenses, the subjunctive mood, conditional sentences, and phrasal verbs.

What is advanced basic grammar?

This term usually means mastering fundamental grammar thoroughly and then extending it into more complex structures like perfect tenses, passive voice variations, and inversion.

What are the concepts in grammar?

Grammar concepts include parts of speech, sentence structures, verb forms, punctuation, agreement, cohesion, and style. Advanced concepts build on these basics with more sophisticated usage.

What are the 5 types of grammar?

The five main types of grammar are:

– Prescriptive Grammar: Rules for “correct” usage.

– Descriptive Grammar: How language is actually used.

– Traditional Grammar: Classical rules taught in schools.

– Structural Grammar: Focus on sentence structure and patterns.

– Transformational Grammar: Modern linguistic theory explaining how sentences are formed.

What are 120 rules of grammar?

A: The “120 rules of grammar” refer to comprehensive grammar rules covering all aspects of English, including:

– Parts of speech (nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.)

– Sentence structures (simple, compound, complex)

– Punctuation rules

– Verb tenses and forms

– Agreement, word order, and modifiers

– Advanced structures like conditional sentences, nominalization, and inversion

Conclusion: How to Master Advanced Grammar

Mastering advanced grammar concepts is key to fluency, professionalism, and clear communication in English. By practicing complex sentences, advanced verb forms, cohesion strategies, and formal writing techniques, learners can elevate their English skills significantly. Keep exploring these concepts and integrate them into your daily writing and speaking practice.

Related Pages

Full List of Advanced Grammar Lessons:

- “There” Used As A Dummy Subject (A Quick Guide)

- 200 Wh-Question Examples With Answers

- Advanced Grammar Concepts: Master Complex English Structures

- Adverb clauses

- Appositives In English Grammar: Definition And Examples

- At school or at the school?

- Cleft Sentences in English

- Complex Compound Sentence Examples

- Complex Sentences

- Conditional Sentences In English (Real and Unreal Conditionals – If Clauses)

- Declarative Sentences in English

- Direct and Indirect Objects In English Grammar

- Ellipsis in English Grammar

- Emphatic Structures and Inversion in English Grammar

- Expressing Concession In English Grammar

- Expressing Purpose

- Genitive Case in English Grammar

- Gerunds In English Grammar

- If Only or I Wish (Expressing Wish or Regret)

- If or Unless?

- Inverted Conditionals in English

- Mastering Reporting Verbs in English

- Mastering the First Conditional: A Guide to Expressing Real Possibilities

- Negation in English

- Noun Clauses

- Object vs. Complement

- Parallelism In English: Rules and Definitions

- Phrase or Clause Quiz with Answers

- Phrase vs Clause – What’s the Difference?

- Predicates In English Grammar

- Question Tags In English Grammar

- Questions With Like

- Relative Clauses In English

- Reported Speech

- Reported Speech for Requests and Commands

- Sentence Structure In English

- Subject to Verb Agreement

- The Difference Between As Well As And And

- The Free Indirect Speech in English

- The Passive Voice In English (Definition, Form, And Examples)

- The Subject in English Grammar

- The Subjunctive Mood In English

- Types of Sentences in English

- Understanding the Second Conditional in English: Uses, Structure, and Examples

- Understanding the Third Conditional: Expressing Unreal Past Scenarios

- Understanding Zero Conditional Sentences: Rules, Uses, and Examples

- Wh-questions

- What is a clause In English?

- Yes or No Questions in English

Academic Writing Strategies: How to Improve Your Academic Writing Skills 14 Oct 1:28 AM (17 days ago)

Table of Contents

Academic writing is a formal and structured way of expressing ideas clearly and logically. It is commonly used in universities, research papers, and professional contexts.

Whether you’re writing an essay, report, or dissertation, applying effective academic writing strategies will help you communicate your ideas more clearly and persuasively.

What Is Academic Writing?

Academic writing is formal, objective, and evidence-based. It focuses on presenting ideas logically rather than emotionally. It requires proper organization, clear argumentation, and support from credible sources.

Why Academic Writing Is Important

Strong academic writing demonstrates your ability to think critically, analyze information, and communicate effectively. It also helps you develop essential skills such as reasoning, organization, and attention to detail — all of which are valuable both in academic and professional settings.

The following sections offer effective strategies to improve your style in academic writing.

Top Academic Writing Strategies

Here are some of the most effective strategies to help you improve your academic writing skills:

1. Understand the Task and Purpose

Before you start writing, make sure you clearly understand what is required. Identify the type of writing (e.g., essay, report, analysis) and its purpose — whether you need to explain, argue, describe, or evaluate. Misunderstanding the task is one of the main reasons students lose marks.

Also, consider three key questions before you begin:

- Who is writing? → Understand your role as the writer (e.g., a student, researcher, or observer).

- What are you writing about? → Define the topic and genre (essay, case study, reflection, etc.).

- To whom are you writing? → Identify your audience (your professor, academic peers, or a general reader).

Clarifying the audience, purpose, and topic helps you choose the right tone, structure, and level of detail. It ensures your writing is relevant, focused, and appropriately formal.

2. Plan Before You Write

Before you start writing, take time to brainstorm ideas and create a clear outline. Organize your thoughts into three main parts: introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion.

This structure helps you maintain a logical flow, ensure each paragraph supports your main argument, and avoid going off-topic. Good planning also saves time during revision and improves overall coherence.

3. Write a Clear Thesis Statement

writing tipYour thesis statement expresses the main idea or central argument of your essay or paper. It tells the reader what your paper is about and what position or perspective you will defend or explain.

A strong thesis is precise, arguable, and focused. It serves as a roadmap for your entire piece of writing, guiding both you and your reader.

A. What Makes a Good Thesis Statement?

A clear thesis statement should:

- Answer the question or task given in the prompt.

- Take a clear stance or position (especially in argumentative writing).

- Be specific, not too general or vague.

- Appear in the introduction, usually at the end of the first paragraph.

B. Example of a Weak vs. Strong Thesis Statement

| Weak Thesis | Why It’s Weak | Strong Thesis | Why It’s Strong |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pollution is bad for the environment. | Too general; doesn’t show direction or focus. | Government policies should focus on reducing air pollution in urban areas to improve public health. | Clear, specific, and takes a position. |

| Students need to study more. | Vague; doesn’t explain why or how. | Consistent study habits and time management are essential for academic success among university students. | Focused and explains how the idea will be developed. |

| Social media has advantages and disadvantages. | Too broad and obvious. | While social media connects people globally, it also increases the risk of misinformation and online addiction. | Balanced and clearly states both sides of an argument. |

C. Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Writing a statement that’s too broad or vague.

- Simply stating a fact instead of an argument.

- Trying to include too many ideas in one sentence.

- Changing your thesis halfway through your essay.

💡 Quick Tip

If you can answer “What am I trying to prove?” or “What will my essay show?” in one sentence, you probably have the foundation for a strong thesis statement.

4. Organize Ideas Logically