Strength in the Silent Era 22 Sep 11:19 AM (last month)

How does a strong man make a living? For Joe Bonomo (1901-1978), his strength opened doors for several career paths, including work as a stunt man and actor in Hollywood. Thanks to the Victor (Vic) Boff collection at the Stark Center, we can all enjoy a glimpse into Hollywood’s silent era and early “talkies” through the photographs of Bonomo’s career over the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s.

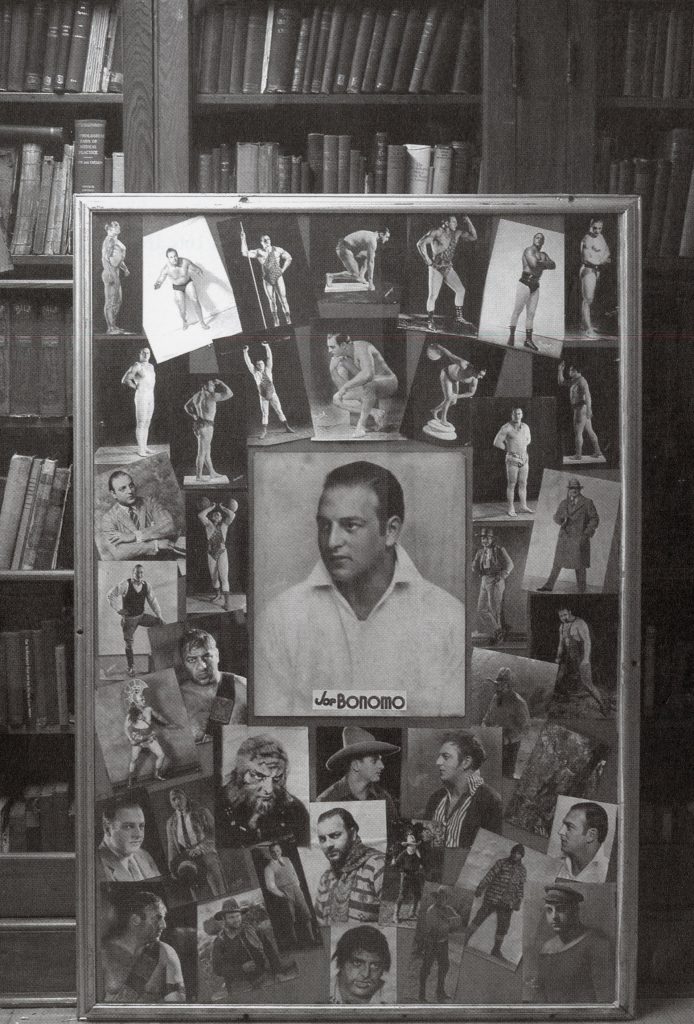

Vic Boff (1917-2002) was a strongman, athlete, editor, entrepreneur, author, and historian. Bonomo was good friends with Boff and gifted him two large, framed collages of photographs of himself throughout his career. An image of one of the collages is shown below.

When Boff donated the collages to the Stark Center, librarian Cindy Slater removed the photographs to preserve them. More information about the conservation of these photographs can be found in my previous blog post, “Preserving Legends: The Victor (Vic) Boff Collection.”

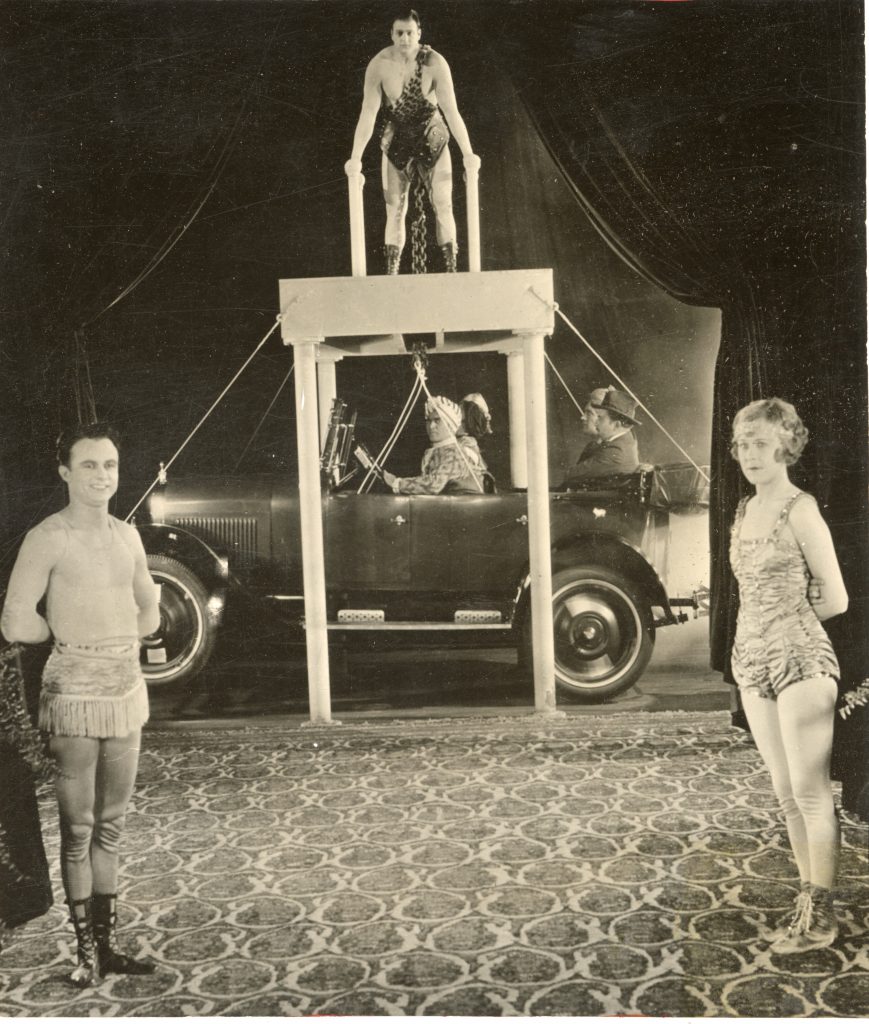

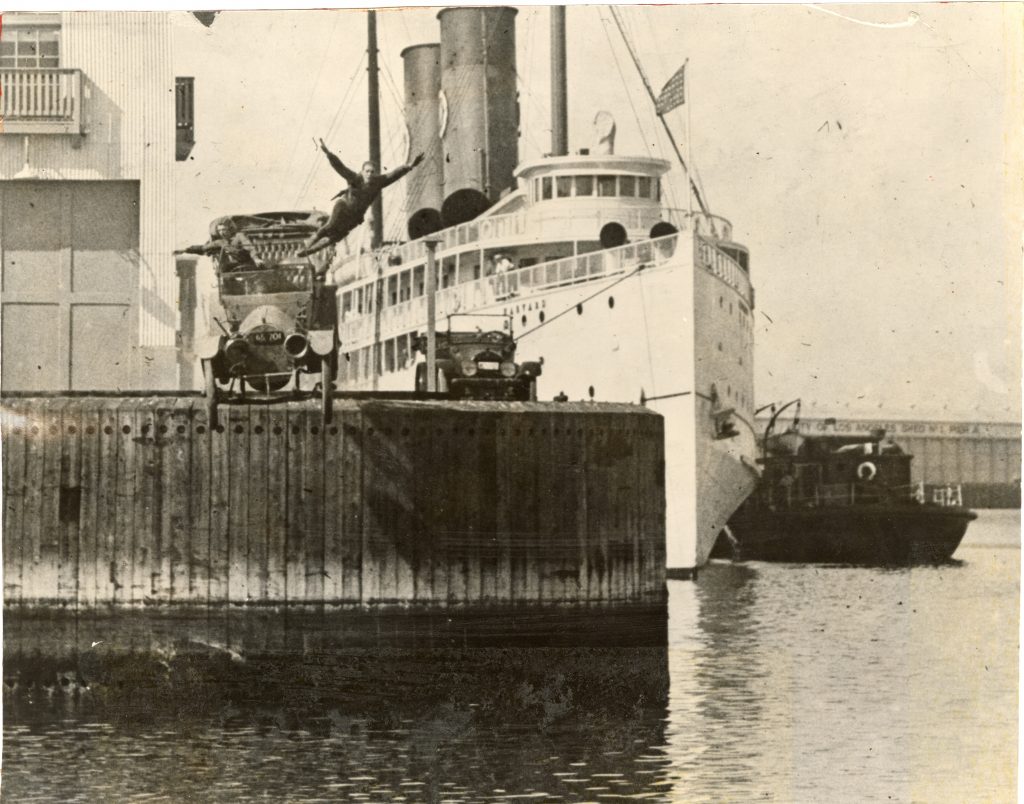

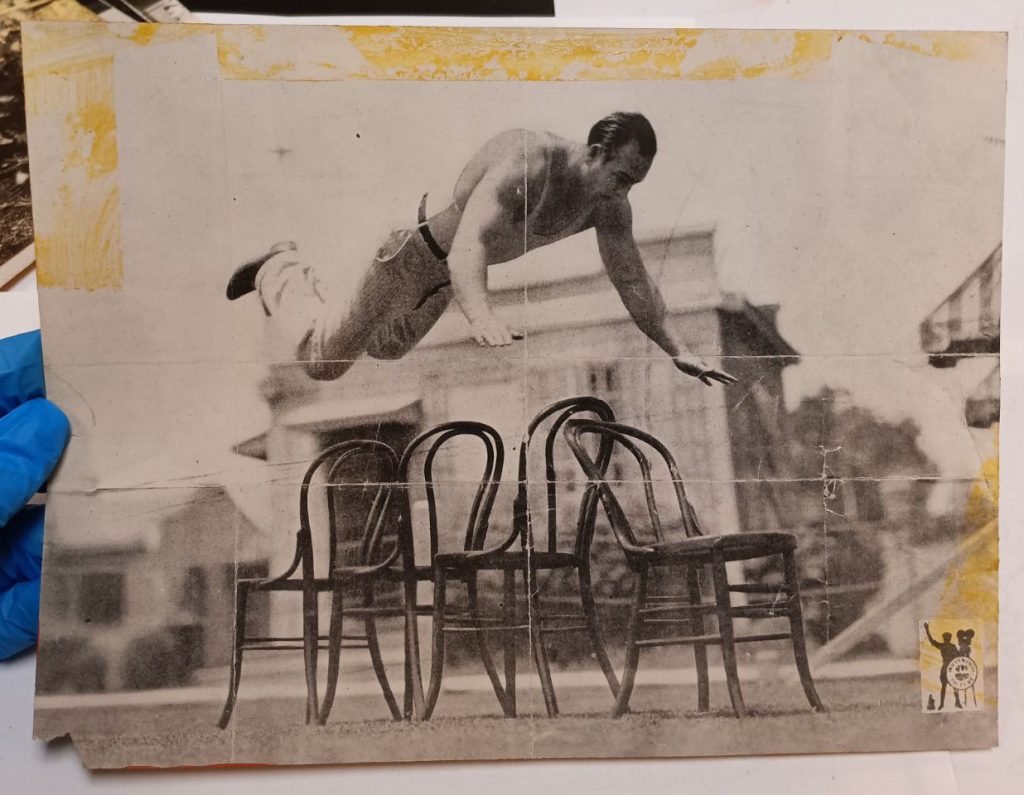

Bonomo first got into movies in 1921, when he won the “Modern Apollo” contest at nineteen years old and received a thousand dollars and a ten-week movie contract to star with actress Hope Hampton in the silent film “The Light in the Dark” (1922). He performed various stunts in the movie for multiple actors, including Lon Chaney. The photograph below is believed to be from this film.

Bonomo got his next big break in 1923 when he signed on for a seven-year contract with Universal to be a stuntman and stock actor. He moved to Hollywood and doubled for Lon Chaney again in “The Hunchback of Notre Dame.” He served as Chaney’s double in several more movies throughout the years. His next big roles were in serial films like “Beasts of Paradise” (1923), “The Iron Man” (1924), co-starring with Italian actor and stuntman Luciano Albertini, “Wolves of the North” (1924), “The Great Circus Mystery” (1925), and “Perils of the Wild” (1925), a series based on the story of the Swiss Family Robinson.

Most of the photographs of Bonomo are from silent era films that no longer exist. According to the article “Lost Treasures of Silent Film Tallied,” it is estimated that 70 percent of the 11,000 silent films created in America between 1912 and 1929 have been destroyed. A big reason for this is because of the fragility of the nitrate film they were made with, which is highly flammable. Large studios like Warner Bros. and 20th Century Fox lost massive amounts of films in fires during the 1930s. Other films were intentionally destroyed by the studios to make room for newer, more popular films. Materials preserved by actors in these movies, like Bonomo, have left us evidence of these otherwise lost artifacts.

Not all the photographs in this collection had information to identify which movies of Bonomo’s they were from, so organizing and identifying the photographs took some detective work. One source of information was Bonomo’s autobiography, The Strongman, published in 1968. This book featured several of the photographs included in the collages as well as context for the films. Another source was the Internet Movie Database (IMDb). Although I was unable to identify films for every photograph, I was able to recognize several different movies including “The College Cowboy” (1924), “The Great Circus Mystery,” “Perils of the Wild,” “The Vanishing Legion” (1931), “The Sea Tiger” (1927), “Wolves of the North,” “Vamping Venus” (1928), and “The Sign of the Cross” (1932).

These photographs have been digitized and are available to view online through The Strongman Project. The Victor (Vic) Boff Collection and publications of Bonomo’s are available to researchers at the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports. You can learn more about the Center’s holdings by visiting www.starkcenter.org.

Sources, in addition to the records themselves:

Bonomo, Joe. The Strongman: The Daredevil Exploits of The Mightiest Man in The Movies. New York: Bonomo Studios Inc., 1968.

“Lost Treasures of Silent Film Tallied.” American History 49, no. 1 (April 1, 2014): 10. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=e863689c-4a6c-35ee-a4c3-701d9e266a43.

The Visual Legacy of Jack H. Hughes 14 Jul 8:02 AM (3 months ago)

The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports is a nonprofit that receives the funding to preserve and provide access to archival materials in the fields of physical culture and sports through the generosity of private donors. This being said, there are so many wonderful collections that are inventoried but not completely processed. While we are mighty in spirit, enthusiasm, and dedication, there is only so much our little band can accomplish. In an effort to share these amazing pieces of history, we photograph and upload artifacts into our online catalog system so that we can use them in blogs, visual exhibits, academic papers, and in several other ways to bring exposure until they are processed by our archivist, Caroline Jones, when she completes finding aids for them.

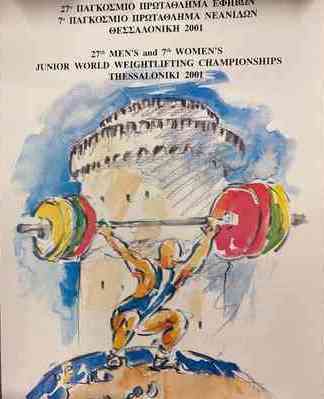

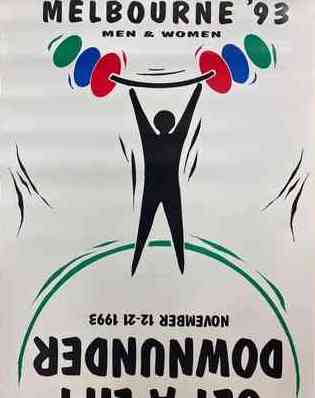

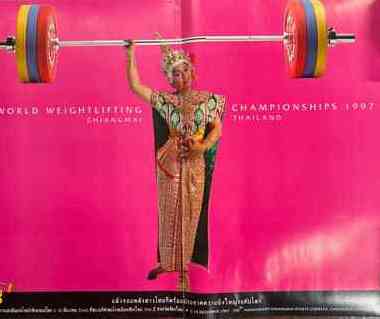

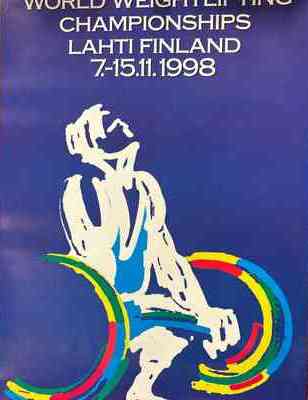

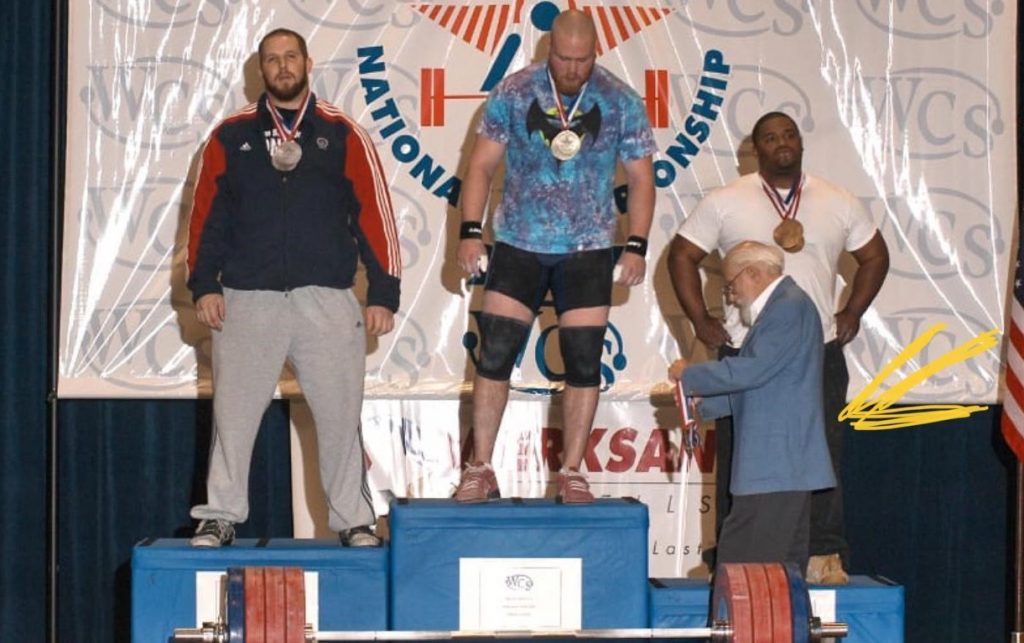

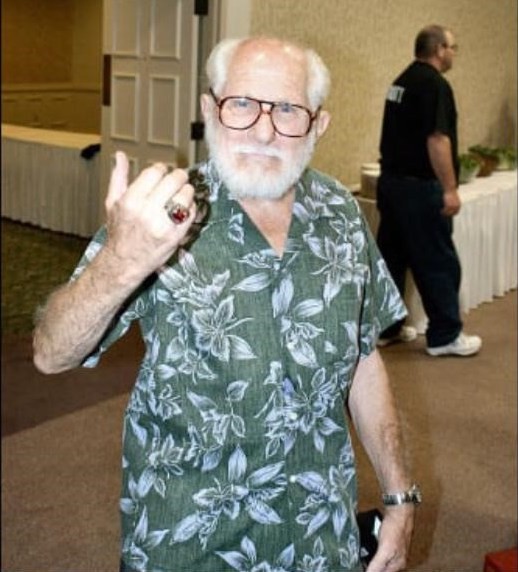

I was making my way through the archives recently, opening boxes at random like I was the Grinch checking out the Christmas presents in the houses he’d stolen into, peeking in to see what treasures were hiding inside. To my wonder and delight, I found the Jack H. Hughes Collection. Mr. Hughes graciously donated 84 Powerlifting and Weightlifting posters. These posters spanned many years of national and international competitions and the artwork on nearly all of them is visually stunning.

Jack Hughes passed away at 96 years old in Los Angeles, California in 2017 and had an impact on many powerlifters and weightlifters. Not only was he a weightlifting champion in his own right, but he was a well-respected referee as well in national and international competitions, and even in his own back yard in Venice Beach. We are so grateful to have his collection and making these items accessible to students and researchers who study the world of physical culture.

2018 Strength and Power Hall of Famer, Artie Drechsler, said of him,

“Jack [Hughes] was one of the greatest referees in the history of weightlifting and powerlifting (he was national champion in weightlifting, and a national masters record holder in powerlifting as well – so he didn’t just judge it, he did it). His contribution to officiating on a national and international level was immense, both in its scope and length. He will live on in the work and memories of so many to whom he taught the values of integrity, dedication, and competence. I am fortunate to count myself among his pupils.”

Thank you, Mr. Hughes, for your impact on the sport of weightlifting and powerlifting and for your donation of these wonderful posters to help preserve the history of the sport you so loved.

The 1914 Football Team Goes Deep 30 Jun 9:56 AM (3 months ago)

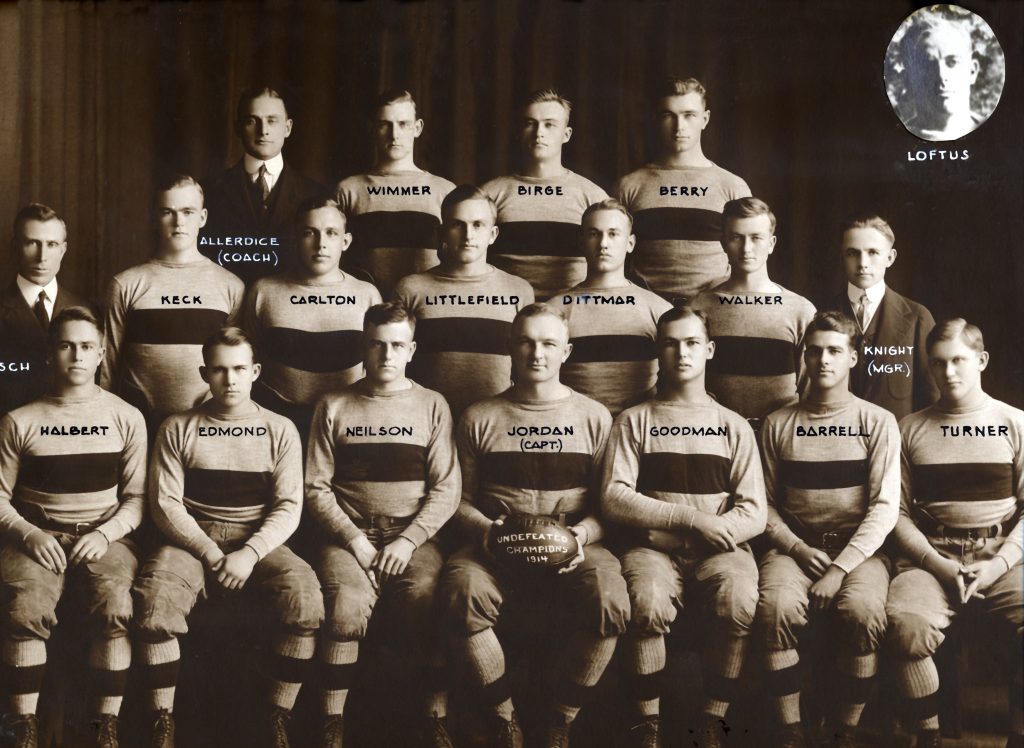

Early in my career at the Stark Center, we developed an exhibit about the 1914 football team, an undefeated, national-championship-winning squad, which was an easy choice of subject given the 100-year anniversary in 2014, the team’s remarkable dominance (they outscored their opponents 358 to 21), and the way the roster had become a veritable “who’s who” in Texas history. Some notable figures include: legendary track coach and founder of the Texas Relays Clyde Littlefield; Louis Jordan, the first Texas officer killed in WWI combat, whose sacrifice was honored in the first dedicated name of this stadium––Texas War Memorial Football Stadium––and, more specifically, with a flagpole purchased by his hometown of Fredricksburg that was dedicated in his name (it now stands in a plaza off the Northwest corner of the stadium); K. L. Berry, who had a military career that included postings along the Mexican border, surviving the Bataan Death March in WWII and a promotion to brigadier general, then Adjutant General of the Texas Military Department; and Len Barrell, who scored 14 touchdowns, kicked one field goal and 34 extra points making him the Longhorn who scored the most points in a single football season for 83 years (until Ricky Williams broke Barrell’s record in the 1997 season). There were fifteen men who earned varsity letters as members of the football team that year. Nearly half of them (7) have been selected for the Longhorn Hall of Honor. Even more, if you include head coach David Allerdice, trainer and future baseball coach Billy Disch, and “Doc” Henry Reeves, the much-beloved African-American athletic trainer who provided medical care to the football players between 1895 and 1915. Those interested for more details should check out Terry Todd’s blog: “Remembering Clyde Littlefield and the 1914 Perfect Season.”

During his senior year in 1910, our patron saint Lutcher Stark served as the manager of the University of Texas football team and cultivated a love of sports, especially Longhorn sports. After graduating, Stark remained tied to the Forty Acres by becoming its greatest benefactor and serving a record 24 years as a member of its board of regents. In the early days of his philanthropy, Stark purchased blankets during the 1914 season for each member of the Longhorn football team, so they could keep warm on the sidelines. The blankets featured the words “Texas Longhorns” and the image of a longhorn steer. Much more detailed than the current logo, the longhorn sewn onto these blankets showed the head and face down through the neck and shoulders. University of Texas teams had been referred to as the “Steers” and “Longhorns,” but, at that time, they were more commonly referred to, simply, as “varsity.” We credit these blankets gifted by Stark in 1914 as foundational brand building that permanently marked the University of Texas identity.

Soon after opening the 1914 football exhibit, we began a new project constructing a large, custom display case on the wall across from our reception desk, where we now showcase one of the original 1914 blankets purchased by Lutcher Stark. This one belonged to Theo Bellmont, who was hired as the University’s first Athletic Director in 1913. It was donated by Bellmont’s grandson and friend of the Stark Center, Jack Gray. The display case we built to tell the story of the 1914 blankets is the largest in our galleries and it includes a letter jacket presented to Stark in recognition of his service, correspondence (on loan from Walter Riedel) from the 1910 season in which Stark, acting as team manager, organized match ups and travel, plus a selection of photographs. Before we had finished installing all the elements in the case, we were contacted by Dr. Corwin D. Martin, a private collector in Arizona, who knew nothing of our plans for the new display, but had acquired and wanted to donate Len Barrell’s leather cleats, which had run for and kicked all those points during the 1914 season. We graciously accepted and quickly altered the exhibit design to include them. The most remarkable detail about Barrell’s cleats is that visitors can clearly see each cleat was individually tacked into the sole of the shoe.

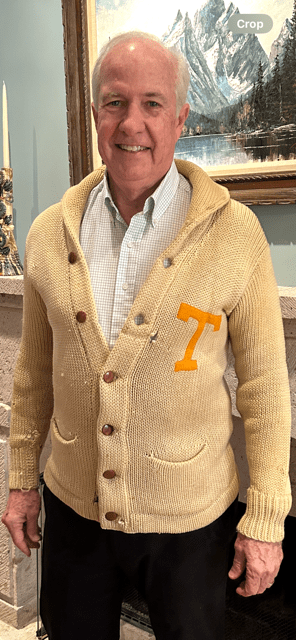

And now, friends, the history of that 1914 football team and the Stark Center’s connection to it continues to develop. Last fall I was contacted by my new friend John H. Keck, who informed me that he was the grandson of Ray Keck, a member of that great, undefeated team. Mr. Keck was in possession of his grandfather’s letter sweater and curious if he could loan it to us for display. I said, “Of course!” So, John and his wife Ceci came to Austin last month and delivered grandfather Ray’s letter sweater—but not before John decided to try the sweater on himself and snap a photo. I gave them a tour of the Stark Center and we spent the afternoon visiting in the conference room. During our conversation, John pulled up photos of a sterling silver medal that Stark had also purchased for the members of the 1914 football team at the conclusion of their season. I was totally unfamiliar with them and John, who’s done a remarkable job preserving his grandfather’s collection, had wonderful photographs of his grandfather’s fully intact medal: a longhorn head with carnelian gemstone eyes with the words “Texas Longhorns” on the front; a banner attached above proclaims “Football Undefeated” with the year 1914; and on the back is the recipient’s name, in this case, “Ray Keck.”

As a result of John and Ceci’s generous loan and visit, we have added more artifacts and expanded the story told by the 1914 Longhorn blanket case. Ray Keck’s letter sweater is now presented beside Lutcher Stark’s honorary letter jacket with an accompanying info panel that features a photo of young Ray in his newly earned letter sweater. Because we permanently house Clyde Littlefield’s collection in our archives, I was curious if his 1914 medal was here at the Stark. I was hopeful because this spring semester, our archivist Caroline Jones had overseen graduate students from the University’s School of Information as they completed a semester long project processing Clyde’s collection. When they moved into more of the objects and artifacts portion of the collection, Caroline had told me there were a significant number of medals. So with help from Caroline, we dove in and found it, Clyde Littlefield’s 1914 football medal. Admittedly, it took slightly longer than expected since Clyde’s medal is missing the “Football Undefeated” banner piece, but we found it and the medal will soon be added to the case, mounted onto the info panel about Ray Keck and his letter sweater, alongside photos of the fully intact medal from John.

But this isn’t where the story ends! John has been hard at work developing a book about the 1914 Longhorn football team and the young men who made up its legendary roster. He commissioned Charles Kupfer, a professor at Penn State Harrisburg, to co-author the book with him. Kupfer completed his PhD in the American Studies program at the University of Texas in 1998. He is a friend and former classmate of our museum director, Jan Todd, who completed her PhD in the American Studies program in 1995. The book is called “A Team of Champions” and will be published by Texas A&M University Press with an expected release in mid-2026. John has included in the manuscript his grandfather’s collection of photographs, memorabilia, and personal notations. I can already tell you that this book will be a fantastic read. We’ll be sure to help promote its release. So, stay tuned.

Many thanks to John and Ceci Keck who have helped expand our exhibit and deepen our connections to the 1914 Longhorn football team. I’m so glad to count them both as my new friends.

Literature, Philosophy, Rhetorical Theory . . . But Wait, This Is About Women First! 18 Apr 9:46 AM (6 months ago)

I feel obligated to assure you that this blog is in fact about our newest exhibit, Women First! But I want to start by telling you about the Literature and Philosophy lecture course that I took during my very first semester at Saint Edward’s University in the fall of 2006. It was one of four or five lecture course topics available to choose from as all of Saint Edward’s freshmen were required to take a lecture course during the fall semester (very likely the only lecture course offered to students on the Hilltop during that time) which tied in with a respective Rhetoric and Composition class.

In 2006, Literature and Philosophy was taught by two professors. One of them, Dr. Mark Cherry, was remarkable for being late, and for making grand or dramatic entrances whenever he did arrive (often reading aloud from a book or just shouting the opening of his lecture as he burst through the doors and marched down the aisles towards the hall’s elevated stage). And, those of us who paid attention also remember Dr. Cherry, for embellishing the 800CE anointment of Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III into a story with more and more ridiculous details such that by the end of the semester, in Dr. Cherry’s telling, the event occurred not just in 800CE, not just on December 25th, but that the attending parties had actually taken the time to plan and orchestrate the coronation so that the crown was placed upon Charlemagne’s head at the exact moment the twelfth stroke of midnight rang out across the empire. The absurdity of pushing the story into such unknowable detail drove Dr. Cherry’s counterpart (and, later, my friend) Dr. Harald Becker to hysterics. All the young people in the audience, paying attention or not, seemed to miss the joke.

As a result of completing this Literature and Philosophy course, I can almost remember the full reading list of mostly forgettable literature (Kafka, Hesse, some other guys…?), but also some really wonderful literature (like Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye) and I can clearly remember all of Dr. Cherry’s fictional details in Charlemagne’s coronation, but I have no idea why the story was told and re-told so many times over the course of the semester. Oh well.

Now, I’ve told you about Dr. Cherry and the Literature and Philosophy course at Saint Edward’s University in the fall of 2006 for two reasons. The first reason is because as I worked on and have since completed Women First!, I find that I have begun embellishing its origin story, Cherry-style, into such fantastic detail that in the most recent tellings, I am sitting down with Jan Todd, our museum director, at the long table in the Stark Center’s lunch/break area on Friday, January 31st and, literally, on the fifth stroke of five o’clock in the afternoon, as the lights are beginning to go out and release us to the weekend, Jan looked at me and told me that she’d like me to start working on a new exhibit about the history of women in sport at The University of Texas. And, we quickly decided, it was to be completed by the first week of March. If you don’t keep score, February is typically a short month and this dramatized origin story is intended to illustrate the fact that I only had four weeks to research, plan, write, design, print and fabricate pieces, deinstall the existing exhibit, patch and paint walls, and then install the new exhibit. Luckily, I work with a wonderful team here at the Stark Center.

Once the greenlight on a new exhibit was fully illuminated, my fellow Stark staff members Patty McCain, Caroline De La Cerda, and Kim Beckwith offered their assistance, however I might need it. I am so grateful for their help, but also for their support, encouragement, and patience. Alysia Transou is a very kind person who volunteers at the Stark Center, typically working with Patty and Caroline on archival projects, and she kickstarted early research by compiling a list of significant moments and figures in the history of women sports at the University. Kristen Wilson, who is a current PhD Candidate in the American Studies department with research interests in women sports and sport history volunteered to help me with some of the exhibit installation, and I am glad to extend my thanks to her as well. There is no way this exhibit would have been completed on time––or tell as thorough and accurate a story as it does––without the time and efforts of Patty, Caroline, Kim, Alysia, and Kristen, my coworkers and friends.

The second reason I began this blog with the story of Charlemagne and my Literature and Philosophy course is to describe how I became the Stark Center’s exhibit designer and my process for adapting history into a museum exhibit. Since I was fifteen and I wrote my first poem that wasn’t assigned as a school project, I have been calling myself a writer. At Saint Edward’s University, I was an honors student and creative writing major. I took courses like Literature and Philosophy, tons of writing workshops, snooze-fests like Technical & Business Writing, and total nerd fodder like Current Theories of Rhetoric and Composition. Since graduating with my Bachelor of Arts, I have written and published short fiction both locally and internationally. I live in a way that I tend to see most things through the lens of storytelling. When I came to work at the Stark Center in 2014, I entered a world and academic field that, at first, felt intensely new to me. I never thought of myself as someone who might work in a research center or gallery space (even if I admired Frank O’Hara, a poet who worked as a curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City), much less one devoted to the subject of physical culture, a term I’d never heard before. But I quickly came to understand museum exhibits in a very familiar way.

Thanks to all the dorky things I learned to think about in Current Theories of Rhetoric and Composition, I came to understand museum exhibits as public narratives which have the opportunity to utilize all available modes of rhetoric in their execution. More simply explained, an exhibit tells a story and, in order to tell the most engaging and efficient version of that story, the exhibit designer or curator incorporates text, photos, art, objects, artifacts, video, sound, music, anything really. Even design, organization, color, and layout are things that a thoughtful exhibit designer will consider when working on a museum exhibit. Once I started to see museums and galleries as blank pages waiting for stories to fill them, I was hooked. I had found my career.

So, after that fifth stroke of five o’clock on Friday afternoon, my first and most immediate task in creating an exhibit about the history of women in sports at UT was understanding the full scope of that story: where does it start and where does it end. Because women still play sports at UT today and continue to face new and evolving challenges, I wanted this exhibit to reach as close to present day as possible. But I didn’t know when women first began participating in sport at the University of Texas. For that matter, I didn’t know when women first began to attend the University of Texas. And that’s where my research began.

I was surprised to learn that women had been a part of the first graduating class at UT. Looking back through some of the earliest editions of the Cactus yearbook, I found an entire page dedicated to a tennis club for women in 1894-1895, the Helianthus Tennis Club complete with illustrations and a list of members. By 1896-1897, the page for the Helianthus Tennis Club included photographs of each member. This became a genesis for the herstory we wanted to tell.

From working at the Stark Center, I was familiar with Anna Hiss, Director of Physical Training for Women from 1921 to 1957, and her wonderful collection that lives in our archives. I knew she played a colossal role in this history and that I could illustrate it with the tremendous amount of wonderful photographs of female students engaging in intramural and club sports from her collection. I was also familiar with the groundbreaking legislation of Title IX and because of the Jody Conradt exhibit I created in summer 2024, I had read about the University’s first women’s athletic director, Donna Lopiano. Suddenly, I had an outline––I had determined a beginning in the Helianthus Tennis Club, I had decided on an ending in contemporary issues surrounding Name, Image, and Likeness, and I had some ideas about pivotal figures and legislation that happened in between.

When I first met with Patty, Caroline, and Kim, we began compiling a list of “firsts” which was what Jan and I decided should be the perspective of this exhibit, a celebration of the various women firsts. With our list of firsts and a broad general history, we divided the exhibit into subsections or “eras” and then I delegated different eras to be researched in detail. In completing our research, we read through many different issues of the Cactus; sifted through articles from The Daily Texan, The Austin-American Statesman, and The Alcalde; tapped into the collections of Anna Hiss, Jody Conradt, the UT Women’s Athletics History Collection, the Texas Athletics Media Relations Collection, and the Texas Athletics Photo Archive; read the history projects of individuals like Billy Dale and his Texas Longhorn Sports Network, Jim Nicar and his UT History Corner. But especially and most importantly, former graduate student Tessa M. Nichols’ 2007 Master’s Thesis, Organizational Values and Women’s Sport at The University of Texas, 1918-1992, proved to be an invaluable guide in our work to create this exhibit.

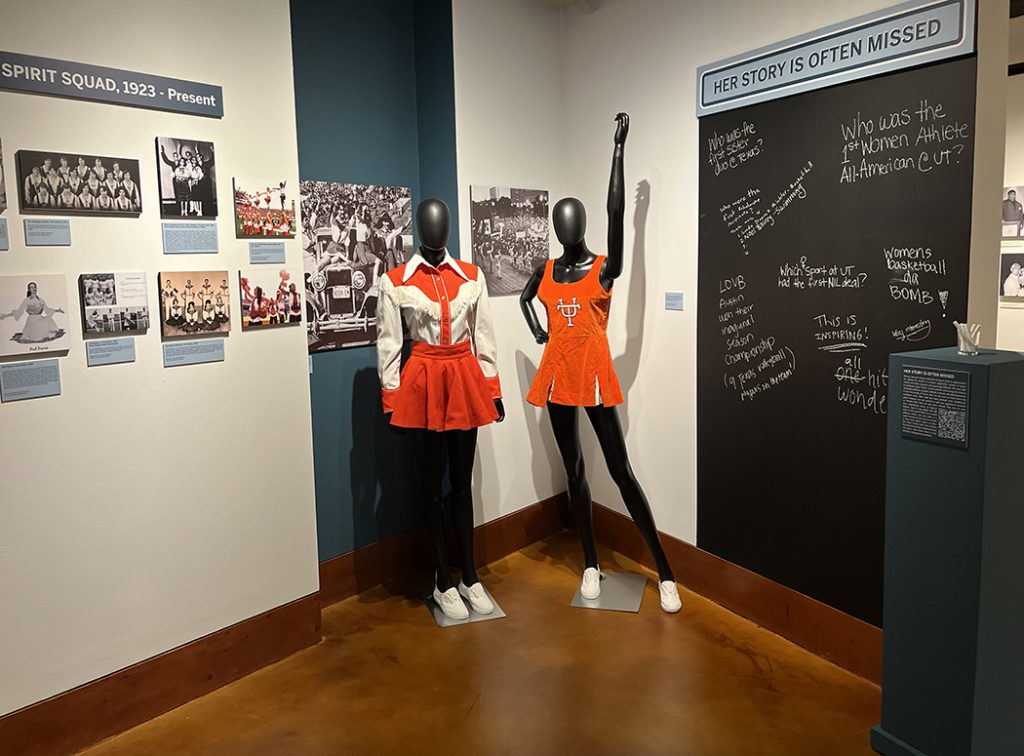

Then, we began writing the first drafts of text panels, which I later edited and pared down to individual captions. From those early texts, I was able to curate the exhibit. It’s one thing to write out a text-based history, but the next step is translating that history into a public exhibit. The challenge becomes sifting through our collections and resources to determine what photos, artifacts, documents, periodicals, sporting equipment, trophies, clothing, and other items will help me present a thorough and layered narrative. For certain parts of the story, I had a wealth of resources to work with; in others, I was severely limited. For example, in that early era before Title IX when the University approved the formation of the first intercollegiate teams, even the Cactus yearbook failed to present team photos that were distinctly identified as intercollegiate versus intramural or club. It wasn’t until 1970 that I found photographic evidence of these early teams. Once all photos and artifacts were chosen from our collections at the Stark Center, I began designing the exhibit layout in its assigned space. This means I took exact measurements of each wall in the exhibit’s designated gallery space and, while looking at the floorplan, I started to consider how I wanted the exhibit to invite and guide visitors through its herstory and which walls had the appropriate amount of square footage for the different eras. I began to think of these sections as “chapters” in the story.

Jan and I had also talked about incorporating pops of color on the gallery walls. I chose a shade of blue-green called azalea leaf. The fresh color helped me give a visual organization to the breaks between different eras in the flow of the exhibit. I also decided to add large headers to each era, giving it a title and presenting its time frame. These strategies were meant to engage as many museum visitors as possible. Exhibit designers typically think about three distinct types of visitors: 1. the speed walker, who motors through the exhibit, absorbing only what can be seen or read without breaking stride; 2. the reader, who spends the entire day at the museum, reading every publicly displayed word, sometimes twice; and 3. the in-betweener, who slowly strolls the space, stopping to consider or read select items that especially catch their attention. If you’re curious, even as a person that designs exhibits for a living, I’m a card-carrying member of the “in-betweener” category. Breaks in wall color and the large, text headers provide better opportunities for “speed walkers” to grasp the overarching narrative of the exhibit, while individual photo captions provide more specific details for members of the “reader” category. I also subscribe to the philosophy that museums are living breathing spaces and when I speak to visitors or classes of students, I ask them not to tiptoe or whisper. I urge them to ask questions and engage with each other, talk about what they see or what they think, ideally building a little bit of community in the activity. To further inspire community amongst our visitors, I incorporated an interactive segment in the exhibit.

History has not always reflected an equal value or appreciation for telling the stories of women, especially women in sport, and even more so for women of color. Especially given the time constraints, I knew that my finished exhibit was always going to be incomplete. We were able to celebrate many “firsts,” but there’s much, much more to the story. Anticipating this, I painted a section of wall with chalkboard paint and titled it “Her Story Is Often Missed.” Visitors are invited to write in any significant moment or “female first” that is not found in the exhibit. This can be their own experience, story, or known history. It might also be questions, like who were the first women to receive academic scholarships? It might acknowledge the binary nature of race in our exhibit, which is predominantly White but does include the stories of Rodney Page, the University’s first Black head coach, and Retha Swindell, the University’s first Black female athlete. But what of the Chicano Movement and Mexican-American or Latina students and coaches? How was this history experienced by persons who identify as LGBTQIA+? Not to mention the contemporary era of Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) and the ongoing and evolving issues that the various participants of women’s athletics will face while this exhibit is open. I hope the interactive section provides a space for more stories and productive, engaging discussion.

Women First! is now open and on display to the public. We’ve already had a number of graduate and undergraduate classes come through, as well as individual visitors, and we’re getting wonderful feedback and responses. I hope you’ll make time to visit us and check out the exhibit, too. If there is any way I can be of help or answer any questions, please feel free to drop by the reference desk and ask for me. If you’re not able to visit in person, but you’d like to participate in the “Her Story Is Often Missed” interactive, please send your story to info@starkcenter.org.

The Texas Relays Hits A Century of Meets 7 Apr 8:30 AM (6 months ago)

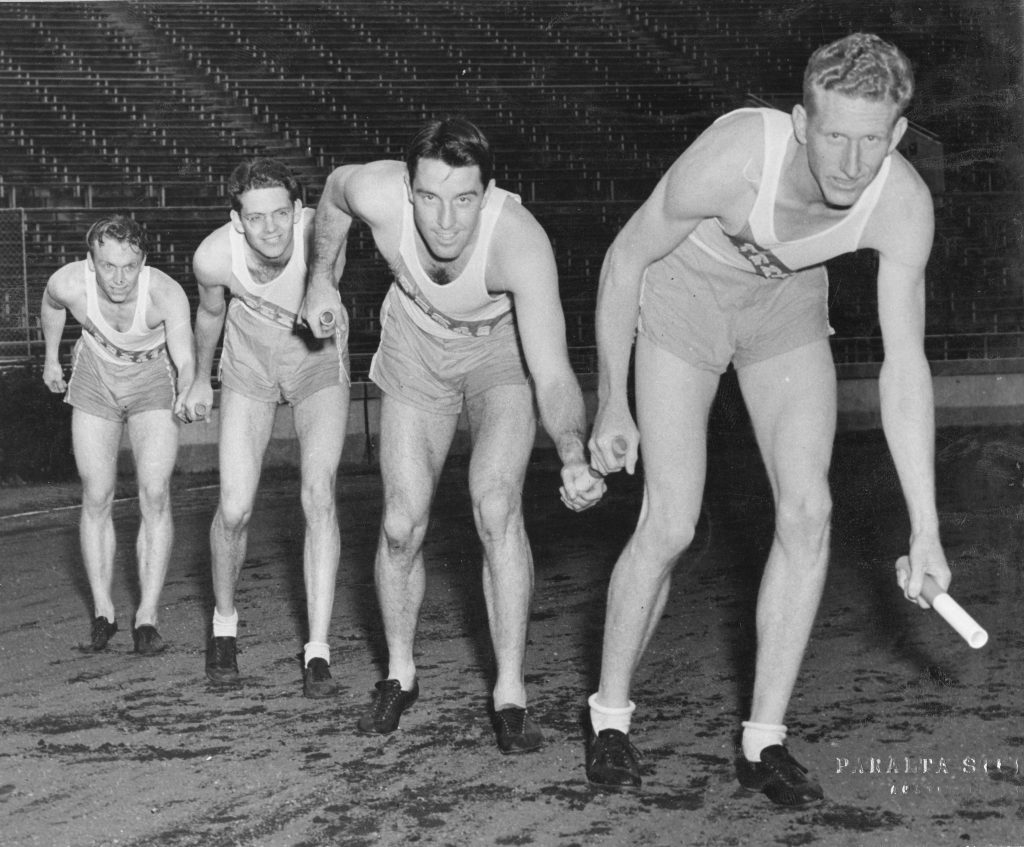

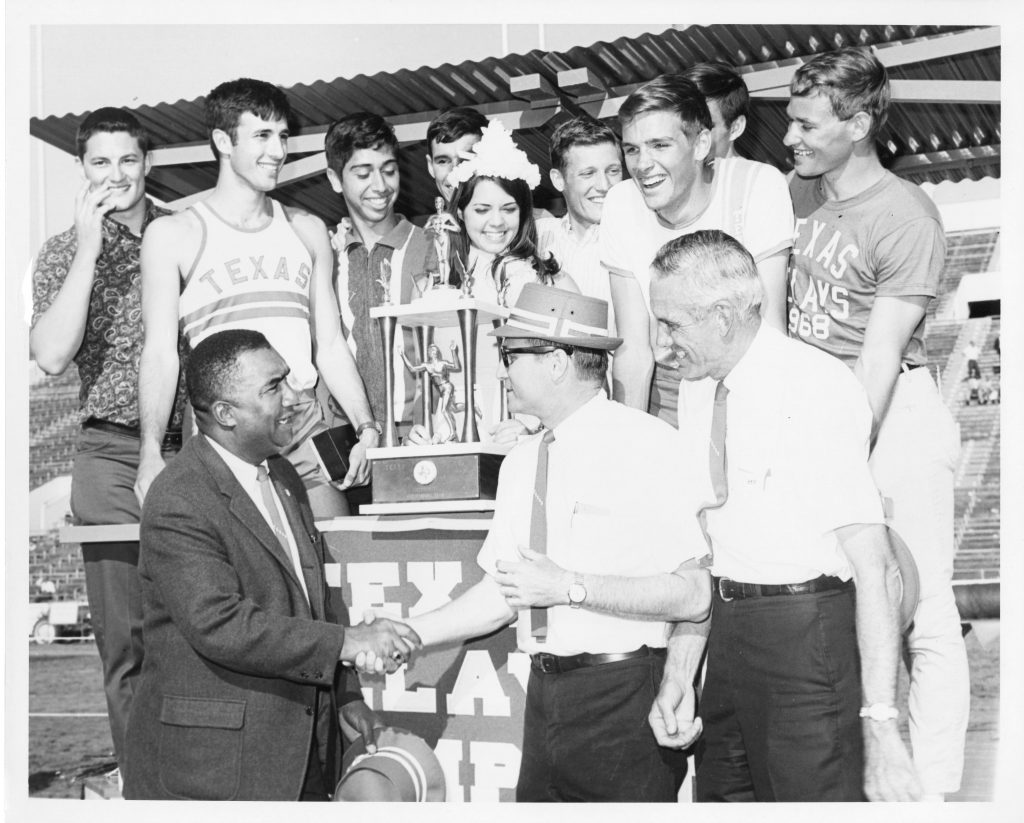

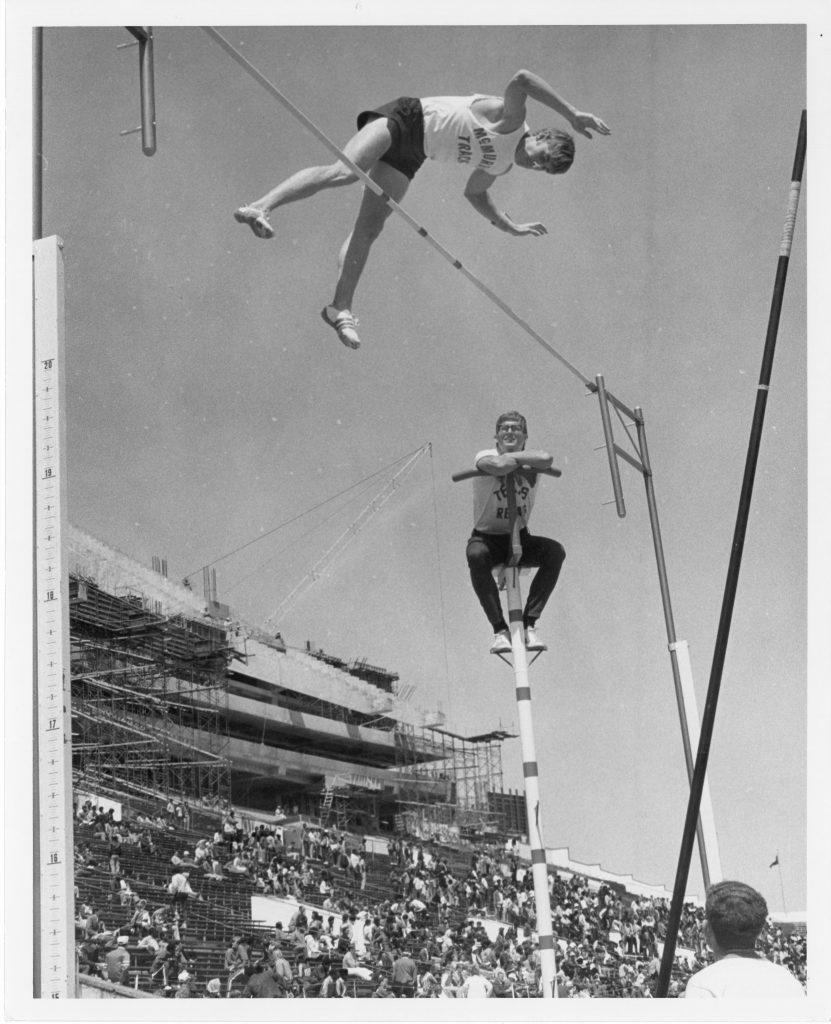

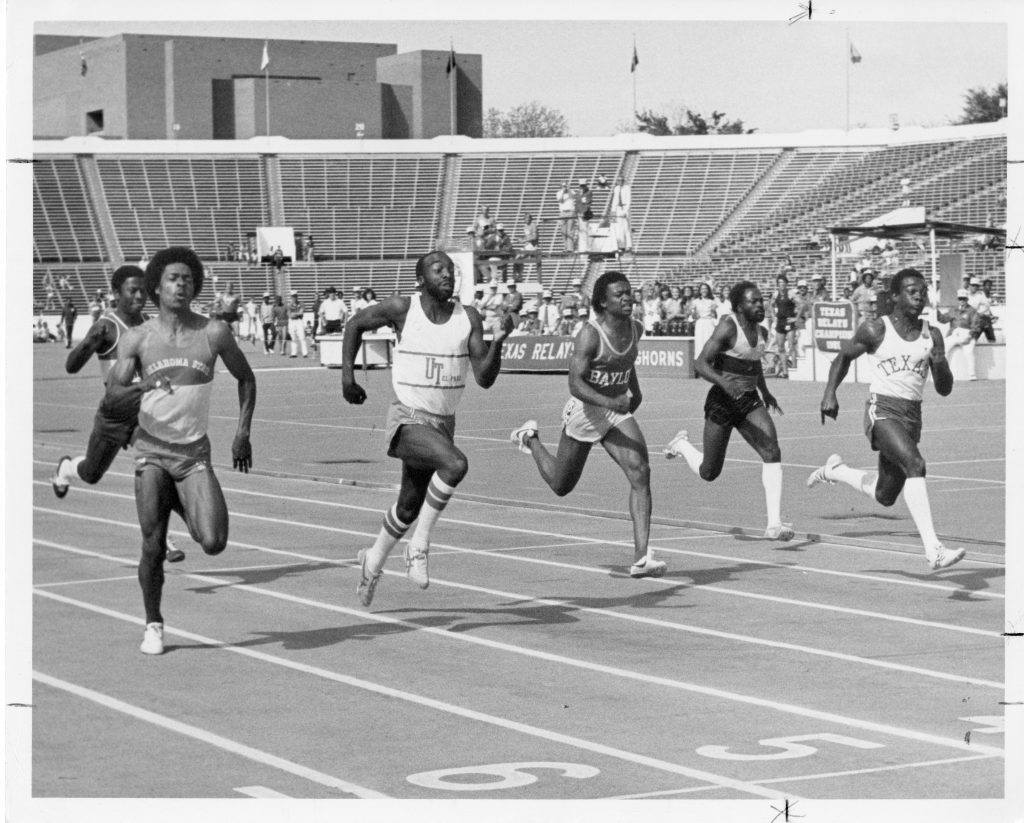

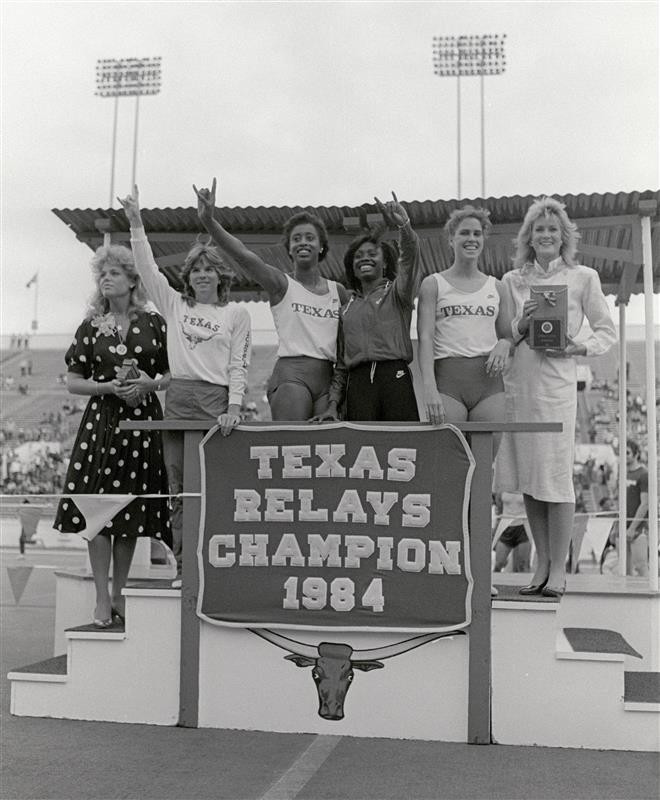

From March 26 to March 29, 2025, the Mike A. Myers Stadium hosted the 97th Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays, a multi-day track and field meet that brings in athletes from all around the country to compete. The meet is the second largest in the United States and features athletes at the high school, college, and professional levels. Many different Olympic athletes have competed in the Texas Relays, such as Johnny “Lam” Jones, Maurice Greene, Gabrielle Thomas, and Ryan Crouser, to name a few. This year, 100 years after the founding of the meet, the Texas Relays was awarded the World Athletics Heritage Plaque in the category of “Competition” by the Museum of World Athletics (MOWA). The purpose of the award is to recognize historic and iconic athletics competitions, careers, performances, landmarks, and media.

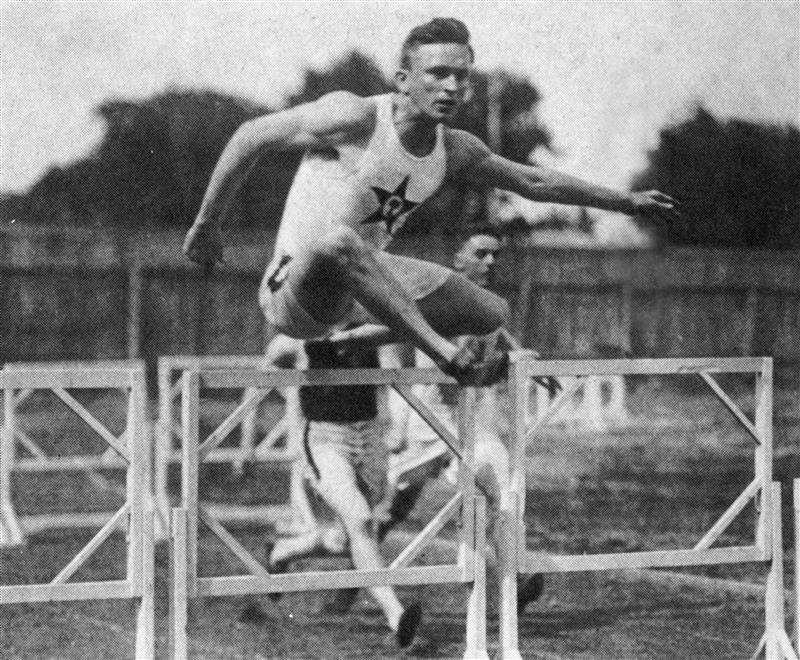

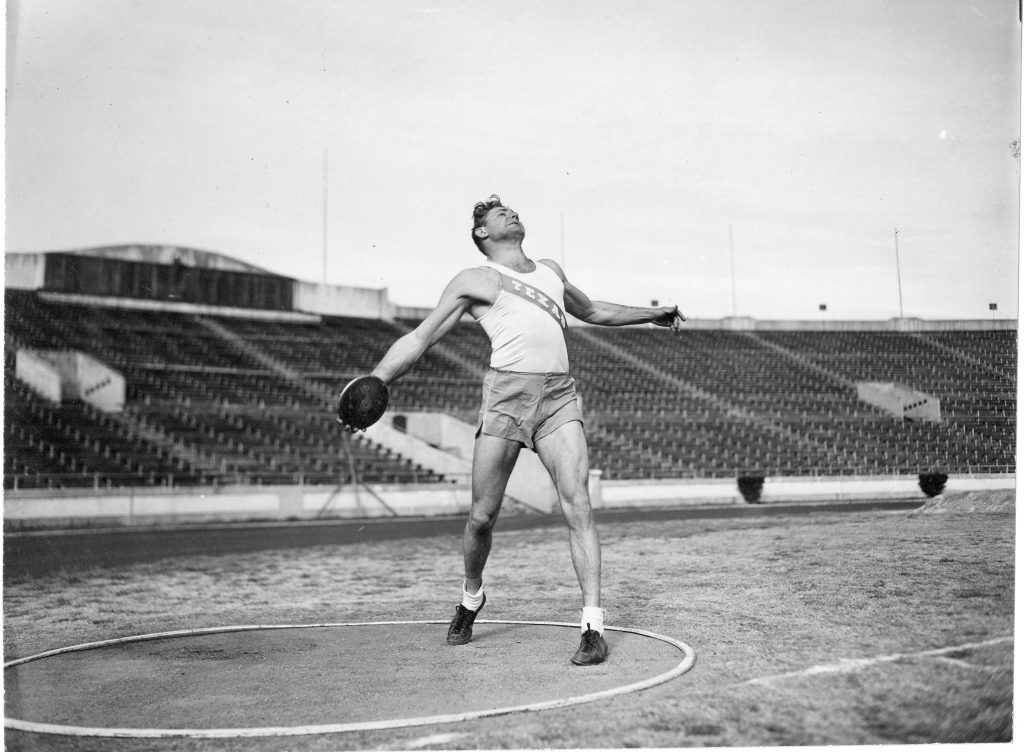

The Texas Relays were founded by Track and Field Coach Clyde Littlefield and Athletic Director L. Theo Bellmont in 1925. Coach Littlefield was inspired to create the Relays after the UT track team traveled to Kansas for a competition and struggled against the cold. He thought his athletes, and other athletes, would be more drawn to Austin’s weather for competition. Littlefield was a decorated athlete in his own right. During his time as a student at UT, he earned 12 letters in football, basketball, and track, and as a sprinter and hurdler he only lost one hurdle race in all four years. He was also an extremely successful coach. Coach Littlefield’s track and field athletes won 131 titles in six different national track meets and 25 Southwest Conference championships.

The inaugural Relays were held on March 27, 1925, in the newly built Memorial Stadium. Over 350 athletes participated, and around 4,000 fans attended. The Texas Relays have taken place every year since, except from 1932 to 1934 because of the Great Depression. Littlefield served as meet director for 32 years until he retired in 1961, and the University officially named the meet the Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays in 1963 (the same year women first competed in the Relays). The Relays eventually moved from what is now called Darrell K. Royal Texas Memorial Stadium to Myers Stadium in 1999.

In addition to holding records of UT track and field athletes, the Stark Center also holds archival records of Clyde Littlefield and his son, Clyde Rabb Littlefield, that are currently being processed by graduate students from the School of Information (also known as the iSchool). The collection was gifted to the Stark Center by the estate of Clyde Rabb Littlefield in 2018 and includes memorabilia, papers, photographs, and scrapbooks documenting the lives of the Littlefield family and Clyde’s career as an athlete and a coach.

Congratulations to the Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays on celebrating this award, its centenary year, and another successful meet in the books!

Sources:

College of Education, The University of Texas at Austin. “Clyde Littlefield.” Profile. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://education.utexas.edu/profile/clyde-littlefield/

Holton, Avery. “History in the making: Tradition of Relays has grown since Littlefield’s creation.” The Daily Texan Online, April 5, 2001. https://web.archive.org/web/20060904114208/http:/tspweb02.tsp.utexas.edu/webarchive/04-05-01/2001040501_s01_Tradition.html

McMicken, Glen. “Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays: A to Z.” 2005 Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays, March 31, 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20070929091800/http:/www.texassports.com/mainpages/txr/2005/040105_11.htm

Museum of World Athletics. “Athletics History- 3000 Years And Counting.” History. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://worldathletics.org/heritage/history

Texas Athletics. “History of the Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays.” News, February 7, 2006. https://texaslonghorns.com/news/2006/2/7/020706aaa_138.aspx

Turner, Chris. “Heritage Plaque marks centenary of Texas Relays.” Museum of World Athletics News, March 24, 2025. https://worldathletics.org/heritage/news/heritage-plaque-marks-centenary-texas-relays

The Boxer at Rest 1 Apr 11:19 AM (6 months ago)

Last summer, I made the decision to expand my academic and professional horizons by pursuing a master’s degree in Sports Management at the University of Texas. The opportunity to learn from leading scholars in the field was too exciting to pass up—even if I do skew the average age of my cohort a bit higher. This semester, I’m enrolled in Ethics in Sport, a course taught by Dr. Charles Stocking. For those unfamiliar with his work, Dr. Stocking is an accomplished scholar who specializes in the history and philosophy of the body, sport, and physical culture from Ancient Greece to the present. His lectures are nothing short of captivating, filled with insights that require deep research to uncover. (For example, I had no idea Socrates was notoriously unhygienic—did you?)

Early in the semester, we examined ancient Greek athletic competitions—chariot races, footraces, and boxing—through the lens of ethical philosophy. We studied thinkers from Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle to Kant and Nietzsche, analyzing how their ethical frameworks intersect with the nature of sport. During this exploration, one athletic tradition in particular captured my attention: boxing.

As a tennis player, I’m drawn to the one-on-one, winner-takes-all dynamic of individual competition. Like boxing, tennis is gladiatorial in nature—no ties, no excuses. The roar of the crowd, the mental warfare, the raw physicality, and the isolation under pressure all echo the intensity of combat sports. But what ultimately drew me to boxing wasn’t the competition itself. It was a statue—The Boxer at Rest—housed in the Teresa Lozano Long Art Gallery at the Stark Center.

My initial interest began while researching for a blog I wrote (the Battle Casts collection) on selected pieces from the Battle Collection of Plaster Casts of Ancient Sculpture currently on display at the Stark Center on loan from the Blanton Museum. Then, during one of Dr. Stocking’s lectures, he explained the brutal simplicity of ancient boxing. There were no rounds or time limits, no weight classes, no holding or clinching, and no rules against striking a downed opponent. Fighters continued until one quit—or died. This context cast The Boxer at Rest in an entirely new light.

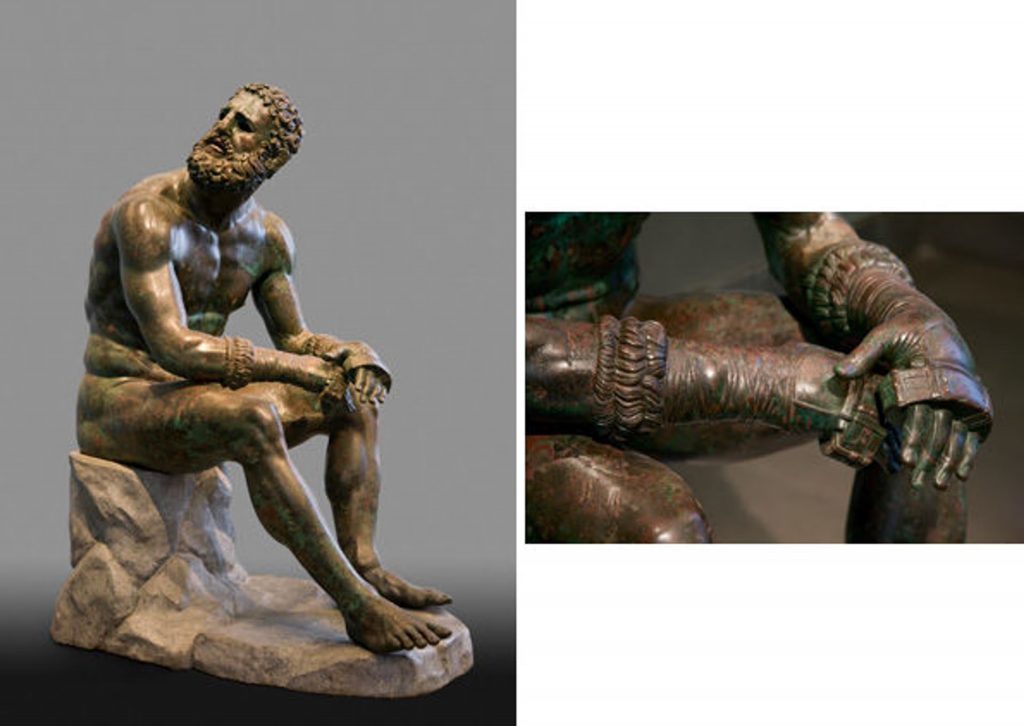

The original bronze statue is a masterpiece from the Hellenistic period (late 4th–2nd century BCE). It was unearthed in 1885 on the south slope of Rome’s Quirinal Hill, buried in the ruins of the Baths of Constantine. In the excavation photo, the figure appears almost aware—like he had been waiting centuries to be seen again. Scholars believe the statue was deliberately hidden to protect it during the invasions that followed the fall of the Roman Empire.

The sculpture depicts a seated boxer, physically and emotionally spent, his arms resting on his knees, head turned slightly to the right, mouth open. He is nude except for his himantes—leather handwraps reinforced with wool padding, designed not for protection, but to maximize the damage dealt to an opponent. His body is covered in cuts, his ears are cauliflowered, his nose broken, and his expression one of exhaustion and pain. A small string, the kynodesme, binds his genitals—an ancient custom meant to preserve modesty and signify athletic discipline.

What captivates viewers most, though, is the ambiguity of his expression. His gaze is weary, introspective, and vulnerable. Some art historians argue it’s impossible to tell whether he’s the victor, the defeated, or simply relieved to have survived. In that ambiguity lies the statue’s power—forcing us to confront not just the violence of ancient sport, but the humanity that endures in its aftermath.

What do a Journalist, Two Professors, and a Couple of Strongmen Have in Common? 18 Mar 11:47 AM (7 months ago)

Reflections on the Stronger Release Party by Rachel Ozerkevich

On a recent Tuesday afternoon, I found myself surrounded by paintings and sculptural reproductions of historical strength heroes, chatting with one of the strongest men in the world. We were discussing the challenges of teaching visual culture to undergraduate students in sport history classes, but I was also getting useful pointers on how to increase my back squat—a lift I’ve been working to improve for nearly a decade (it turns out that my back is likely too weak, and I need to improve my confidence). I’m at work right now, I marveled to myself. My personal, professional, and academic interests were colliding.

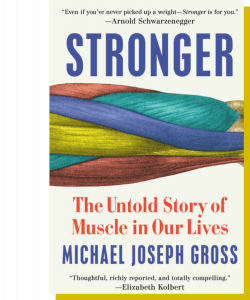

The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports hosted a multi-part release day celebration on Tuesday, March 11th for Michael Joseph Gross’s book Stronger: The Untold Story of Muscle in our Lives. The book had been in the making since at least 2016, when Gross reached out to Dr. Jan Todd and Dr. Charles Stocking, asking them to collaborate. The project evolved into something truly paradigm-shifting: a tome, endorsed by Arnold Schwarzenegger, about the importance of strength training for everybody, written with both journalistic accessibility and academic rigor. This is a combination unlike anything I had seen. I was certainly not alone in this, judging from the enormous turnout at the release event. The crowd was made up of faculty from across the university, students, local Austin residents, and a substantial group of enormous strength athletes. Upon leaving Gross’s reading and the subsequent Q&A from Dr. Stocking, Dr. Todd, and special guests Mitchell Hooper and Martins Licis—each recent winners of the Arnold Strongman Classic and the World’s Strongest Man competitions, with Hooper winning the former in 2025—one undergraduate remarked that he felt so inspired that he couldn’t wait to get to the gym.

I shared in the sentiment. I have been working at the Stark Center since August of this year. I started my academic career as an art historian who also happened to do CrossFit and powerlift in my free time. It was only towards the end of my PhD, when I attended the Stark’s first annual Physical Cultures of the Body Conference in 2021, that I felt like I had found “my people”—that is, others who strength trained in their personal lives and were writing exciting, engaging scholarship about the cultural importance of lifting, exercise, movement, and sport. Much to my delight, I now find myself here as a faculty member, with an office in the same Stark Center that first gave my work a voice and a place.

The event on March 11th was groundbreaking for several reasons. Gross was introduced by Dr. Stocking—himself a seasoned collegiate strength coach, powerlifter, and scholar of ancient sport. Gross’s talk made clear that strength training has immense and wildly underappreciated health benefits for every single segment of society. The strongest men in the world and Holocaust survivors in their late 90s have this in common: though the dose may differ, both populations can, and should, resistance train. All the rest of us who fall between those extremes should be taking up this call to action. Hooper spoke about the role that lifting plays in his life. With a master’s degree in Clinical Exercise Physiology, Hooper has merged his academic background and personal interests to forge a (wildly) successful career in strength. He and Licis (now an accomplished strength documentarian and coach) answered audience questions about their training philosophies, mindset, injury prevention and care, and the role that strength history plays in their practice. Here was a group of academics, writers, speakers, and athletes whom I have long admired all making clear that sport, history, and health can and should align. It’s a simple message that has nonetheless been largely sidelined until now.

My own professional and academic goals have been to merge art history with my personal interests in lifting and physical culture. I’m doing so by examining the specific techniques that sport photographers used before Photoshop to adjust the appearances of strength athletes in the press. But I continue to feel troubled that much academic work on strength remains inaccessible to the people who need the message the most. The public often gets left out of these discussions, seeing professional athletes as unapproachable anomalies and academics as too esoteric. Many of us knowthat lifting is good for us—for our bone density, for our physical and mental resilience, and to prevent age-related muscular decline. And many of us know that the media’s portrayal of strong bodies has an impact on our own body image and ideas about what health “looks” like, for better or for worse. These are topics that unite everyone and yet their discussion, in my experience, has been deeply segmented. This gap dissolved on March 11th: the popular appeal of incredible athletes combined with the empirical expertise of researchers made the topic of strength training seem exciting and accessible. It’s difficult to overemphasize how impactful this was.

Dr. Todd shared with her late husband Dr. Terry Todd a lifelong mission: to give strength training, physical culture, and sport the institutional support they deserve while at the same time including—rather than alienating—the public in the project. Jan and Terry started the Stark Center fifteen years ago to find a home for the incredible collection of strength history material they had amassed during their careers as record-breaking athletes, coaches, and educators. It has since turned into the world’s foremost collection of physical culture and sport history material. It hosts interdisciplinary researchers, visual culture exhibitions, and now, events like this one. Though I haven’t quite been at the Stark for a full year, I understood this event to be the culmination of what the Todds first set out to do in Austin. Sport and strength history have achieved academic recognition in large part thanks to them.

Now the Stark has begun to successfully extend this conversation to the rest of the population. Dr. Todd and Dr. Stocking have both been featured in major media outlets this past month. A recent article in People magazine recounts how Dr. Todd revolutionized the field of women’s strength beginning in the 1970s. As a groundbreaking strength athlete and advocate for women’s lifting, she inspired (and continues to inspire) countless other women athletes to push beyond the cultural limitations imposed upon their bodies and identities. Dr. Stocking, in turn, is profiled in Men’s Health this month, where he explains how strategic yet simple strength training methods inspired by antiquity can counteract modern sedentary work environments. The press that this movement is garnering is gaining steam; the momentum is palpable and will only keep building.

Katie Sandwina and the Legacy that Inspired Jan Todd 21 Feb 11:33 AM (8 months ago)

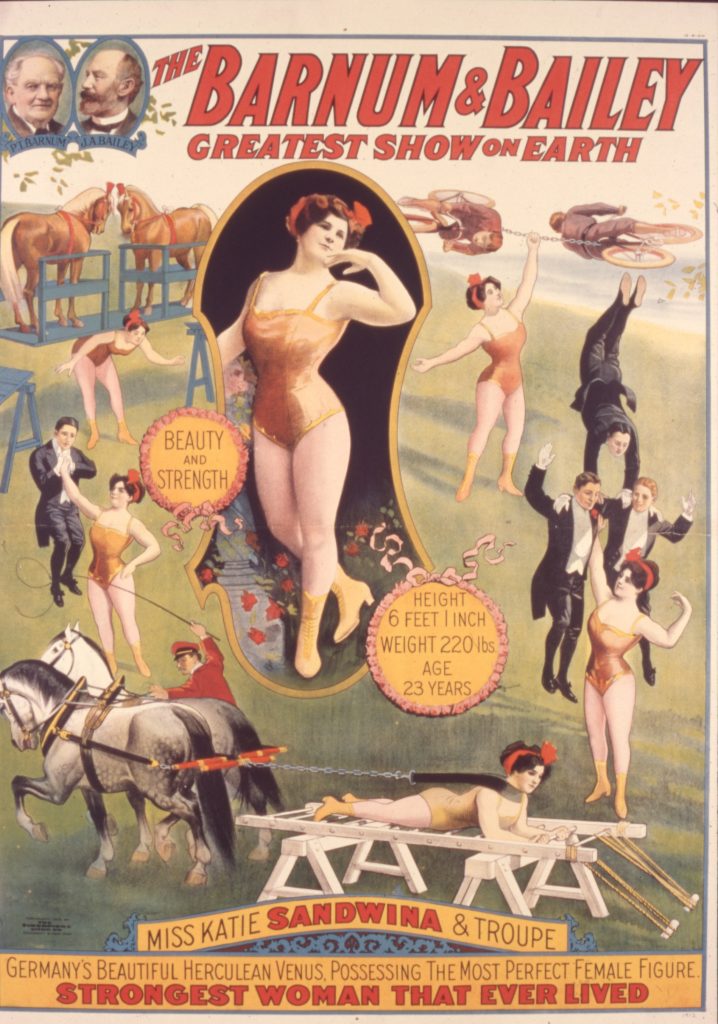

Our Director, Dr. Jan Todd, has always had a special affinity for Katharina Brumbach, or as she is known by her stage name, Katie Sandwina. Dr. Todd began her weightlifting career in 1973 after accompanying her husband, powerlifting icon Terry Todd, to the gym. After deadlifting 225 pounds in her first workout, she asked her husband why there weren’t more women lifting (in 1973 there were no women’s powerlifting, bodybuilding, or weightlifting contests). This was when she first learned of Katie Sandwina, who’d been a center-ring attraction in Barnum and Bailey’s circus during the 1911 and 1912 seasons and possessed “true strength.” From that moment on, knowing that she had trailblazers like Katie Sandwina before her gave Jan Todd the strength and courage to push her own limits in the early days of her career.

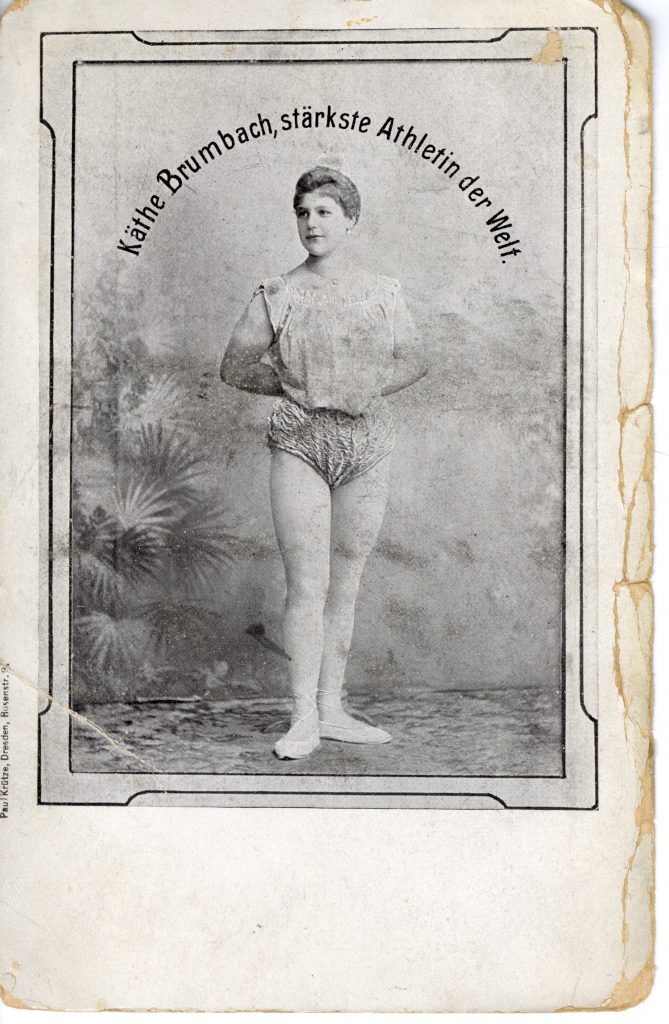

Nearly 5 years ago, in the midst of COVID-19, our former Associate Director, Cindy Slater, found a rare photo in one of the German magazines in the Milo Steinborn Collection and Dr. Todd wrote a blog on it. You can read that here but keep reading mine first!). Dr. Todd has been on a “Sandwina watch” for years to snap up any Sandwina treasures that come up online. Imagine her excitement when another rare photo of Sandwina popped up in January! Naturally, she jumped at the chance to own such a rare photo on a post card, and I was honored to scan it and share it in this blog.

This postcard from around 1901 when Katie is around 16 or 17 years old, is written in German and translates to “Kathe Brumbach, strongest athlete in the world.” This could possibly be the oldest photograph of her.

This postcard from around 1901 when Katie is around 16 or 17 years old, is written in German and translates to “Kathe Brumbach, strongest athlete in the world.” This could possibly be the oldest photograph of her. Back of the postcard in German

Back of the postcard in German

Much has been written on Sandwina as the “World’s Strongest Woman.” Her exploits have been well documented in several articles printed in the Iron Game History journal by Dr. John D. Fair and Dr. Jan Todd, so I won’t go into too much detail here. I’ll share a brief overview to share some of her story with anyone who isn’t yet but will become a Sandwina fan through this reading.

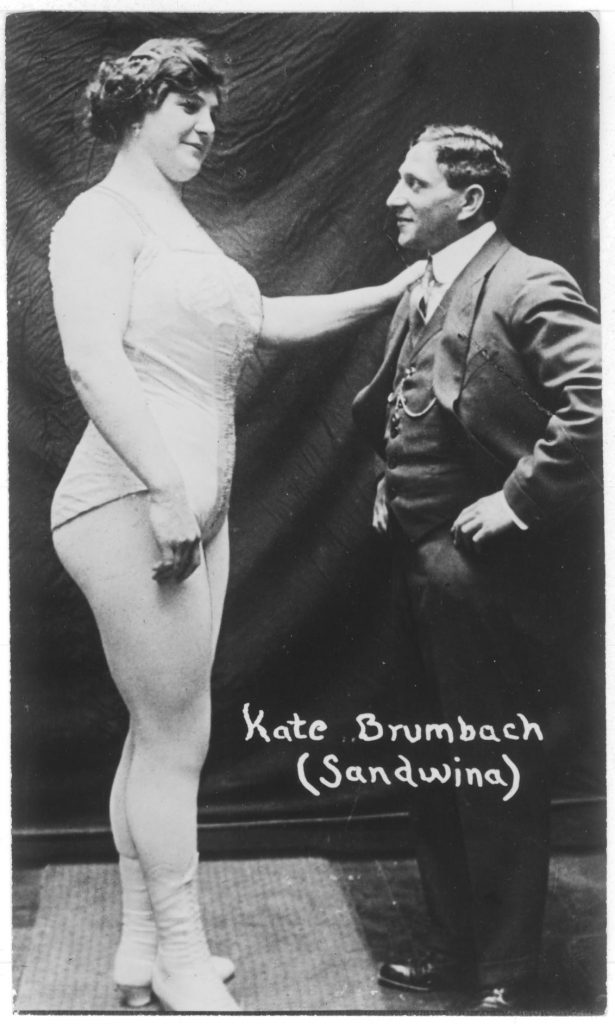

Katharina Brumbach descended from a long line of circus performers. She was born in the back of a circus wagon in 1884 near Vienna, Austria to Johanna Nock Brumbach and Philippe Brumbach. Philippe was one of the strongest men in Germany during the 1890s and stood 6’6” tall, weighing approximately 260 pounds. Katie was the second of 15 or 16 Brumbach children and began performing in her family’s circus at a young age. By her mid-teens, she had grown into a large and powerful woman, performing incredible feats of strength involving human beings on stage, as well as iron-bending and chain-breaking. Her father put up prize money and challenged all comers to wrestle his daughter as part of the act. Max Heymann, an out of work acrobat of considerable repute, accepted the challenge and became one of Sandwina’s victims.

Katie and Max wed around 1900 and began touring together. Max was part of her act, being lifted and swung around in her displays of strength. Contrary to popular belief, she was not an overnight sensation. She and Max toured the U.S. in 1908 and 1909, playing in smaller Vaudeville shows, placing lower on the bills. Son Teddy was born in Sioux City, Iowa on January 25, 1909, while Max and Katie played Benjamin Keith’s Orpheum Vaudeville Circuit. Teddy would become a successful professional boxer in the 1920s and ‘30s, trained by his mother. Here are a few fun videos on YouTube showing some of their training sessions:

By 1911, Sandwina had made it to the center ring of Barnum & Bailey’s Circus and had become New York’s celebrity du jour, after Kate Carew, a progressive and unconventional newspaperwoman, had turned in a full-page article and three drawings for publication in the New York American, glamorizing the “Lady Hercules.” This cemented Sandwina’s status as a major star.

Sandwina toured for many years with Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus until she was nearly 60 years old. Eventually, she and Max opened and operated a bar and grill in Ridgewood, Queens, New York with their two sons Teddy and Alfred, who would go on to become an actor. Even in retirement, she would often perform minor feats of strength to entertain their patrons, including breaking iron chains, bending iron bars, Using Max as a barbell, and laying on a bed of nails holding a plank with an anvil that her husband and sons would beat on with sledgehammers. If you come visit us at the Stark, we have a video playing on a loop with her tossing Max around the bar—very entertaining.

The significance of Katie Sandwina’s celebrity isn’t just that she was known as the World’s Strongest woman. In this day and age, this would be enough. However, at the turn of the twentieth century when women’s roles and societal views on them were largely shaped by rigid gender norms. The Victorian and Edwardian physical ideals of the time emphasized softness and curves. Not only was Sandwina tall and strong, but she also was considered beautiful and fit into the “ideal” feminine appearance. This is patently obvious in the new treasured postcard of her that is now a part of Dr. Todd’s collection. Yep, Katie Sandwina had it all.

Beauty and Strength

Beauty and Strength Katie and Max Heymann

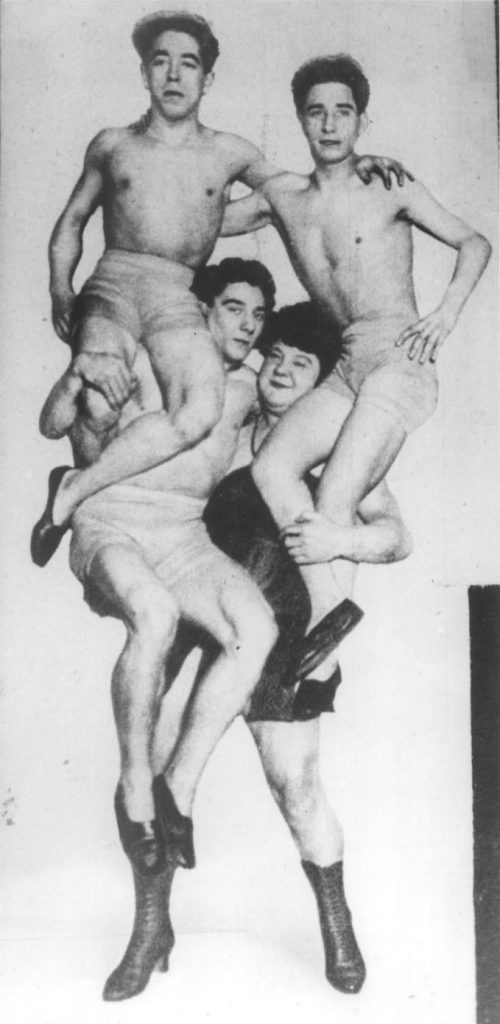

Katie and Max Heymann Sandwina lifting her boys and Max

Sandwina lifting her boys and Max

Preserving Legends: The Victor (Vic) Boff Collection 7 Jan 6:25 AM (9 months ago)

Victor “Vic” Boff (1917-2002) was a strongman, athlete, editor, entrepreneur, author, historian of the Iron Game, and friend to the Stark Center. He was not only interested in physical fitness, nutrition, and health, but wanted to preserve the history of strongmen, bodybuilders, and weightlifters. The Victor (Vic) Boff Collection documents these interests through newsletters, catalogs, magazines, newspapers, and over 300 photographs collected by Boff throughout his life.

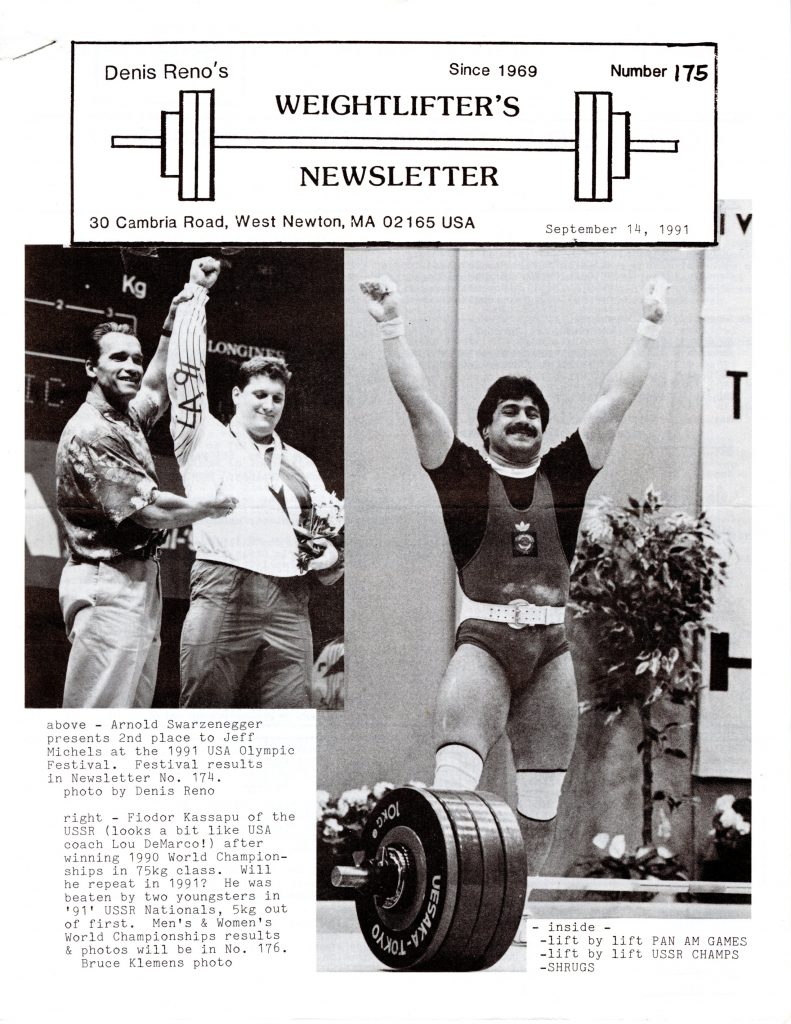

From an early age, Boff was interested in health and fitness. In his teens, he began strength training and performing strongman stunts, in addition to playing sports and swimming in the ocean year-round (something he became famous for as an adult). Prior to moving to New York in 1935, he was a professional boxer and toured with “The Mighty Atom.” He also played semi-professional baseball with the St. Louis Cardinals Rochester farm team. After an unfortunate injury ended his professional baseball career, he began writing for magazines in New York. His first published features were in Let’s Live magazine in 1935. He also served as editor of Healthful Living publications prior to publishing his own books, You Can Be Physically Perfect, Powerfully Strong, in 1975, and Body Builder’s Bible for Men and Women, in 1985. His editorial work is visible in the many clippings and notations on photographs found throughout his collection. There is also a significant number of publications and newsletters related to weightlifting, body building, and powerlifting, like Denis Reno’s Weightlifter’s Newsletter and International Olympic Lifter.

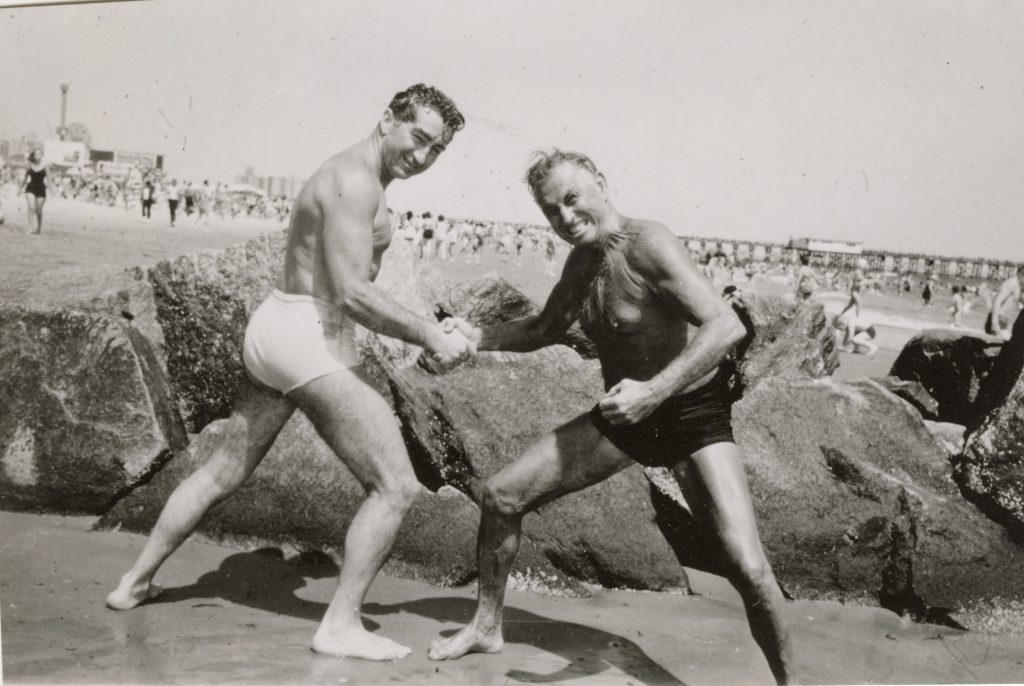

A big part of Boff’s life (and fame) was the Iceberg Athletic Club. The Club, which Boff joined in 1947, was for winter bathing enthusiasts who met weekly at Coney Island Beach and swam together. They believed in the positive effects of cold-water swimming on physical health and fitness and never missed a swim, even during blizzards. He was awarded the title “The World’s Greatest Winter Bather” and served as the club’s President from 1976 to 1992. He was featured in many local newspaper articles about winter bathing, some of which are included as clippings in his collection. There are also several photographs of the Iceberg Athletic Club on Coney Island, like the one below.

Vic was also known for organizing the Association of Oldetime Barbell & Strongmen (AOBS). The AOBS started with a gathering of strongmen for a surprise dinner to honor Sig Klein and celebrate his 80th birthday. The dinner became an annual tradition to honor notable figures in bodybuilding, weightlifting, and powerlifting. Boff also created and distributed newsletters to members, reporting on news within the physical culture community. Boff served as president of the AOBS until he passed away in 2002. After his death, the Highest Achievement Award of the AOBS became known as the “Vic Boff Award.”

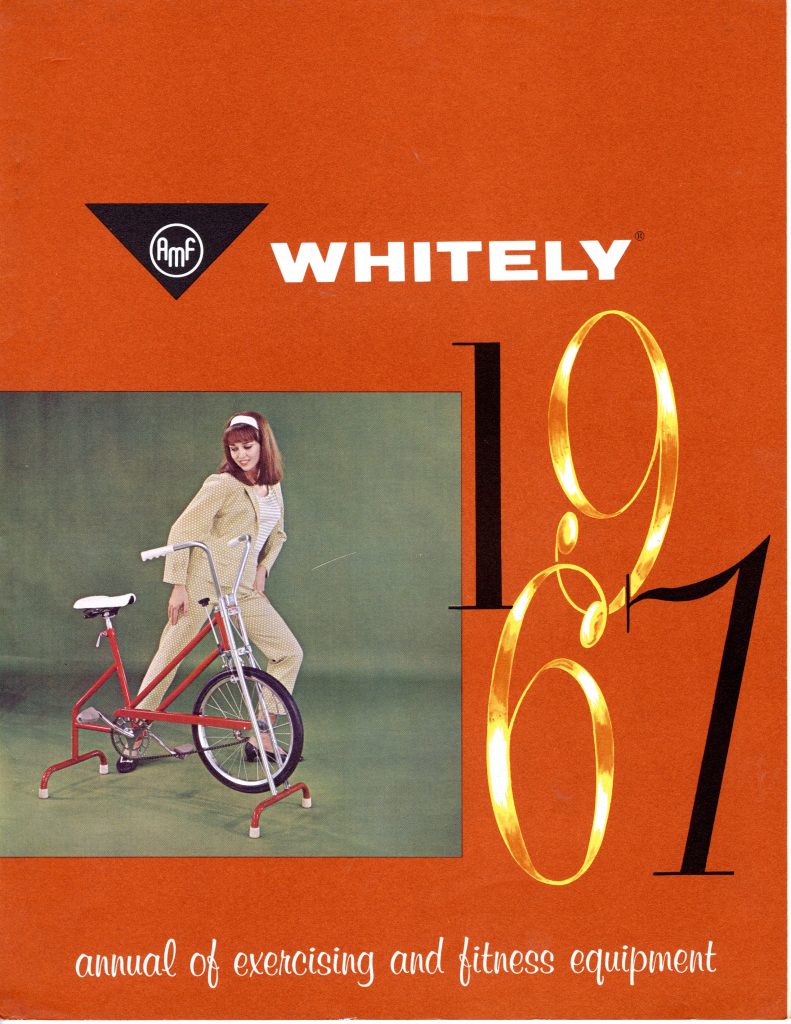

Boff’s collection also documents his business pursuits. In 1950, he opened one of the first health food stores in Manhattan, Vic Boff’s Health and Fitness Aid, which sold books, exercise guides and equipment, supplements, and appliances. Catalogs and advertisements included in the collection show many goods that are common household items today but were not as common back then, like exercise bikes and weight sets for your home, daily supplements, juicers, and water purifiers. He also collected materials on healthy eating habits and the negative effects of tobacco, alcohol, coffee, and steroids.

The photographs in this collection feature many rare shots of the famous strongman and stunt performer Joseph “Joe” Bonomo. Bonomo (1901-1978) was good friends with Boff. He first gained notoriety in 1921, when he won the “Modern Apollo” contest at nineteen years old. Modern Apollo was considered to be the precursor to the Mr. America contests. He went on to find success as a professional stunt man in Hollywood and performed many dangerous stunts throughout his career like jumping from moving trains, wrestling alligators, hanging off airplanes mid-flight, and driving cars off piers, among many others Most of the photographs are from silent films that no longer exist and provide a unique glimpse into the silent movie era.

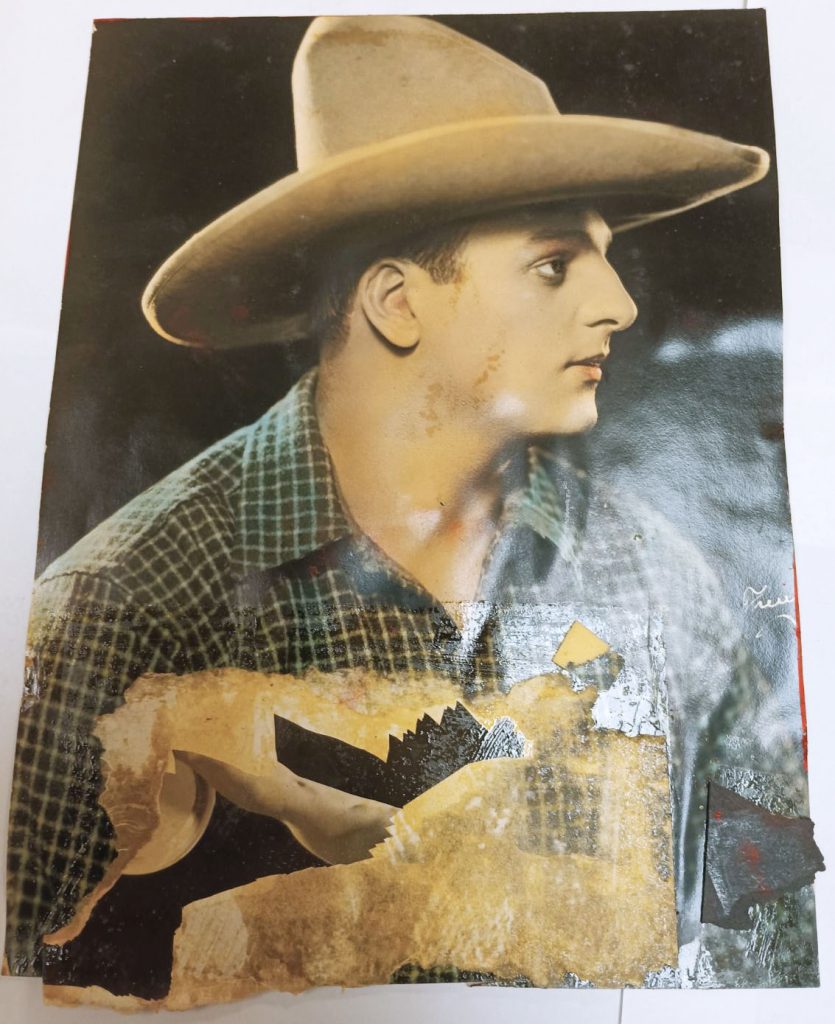

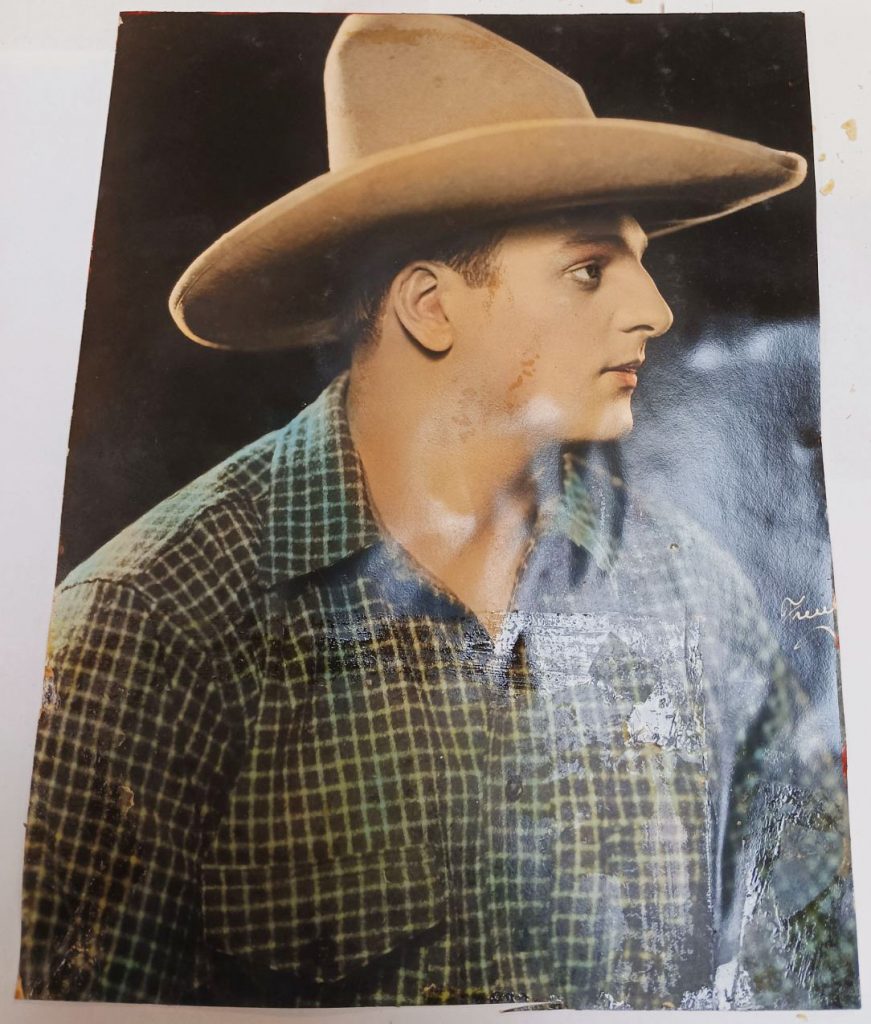

All of the photographs of Bonomo were gifted to Boff in two large, framed collages. When the collages came to the Stark Center, librarian Cindy Slater disassembled them and removed the photographs in order to preserve them. Keeping the collages intact would have further exposed the photographs to the deterioration and off-gassing of the adhesives, which could cause discoloration and acidification of the images or make them very brittle. Some examples of photographs before treatment are below.

The yellow coloring around the sides of the black and white photograph above are stains and residue from deteriorated tape, and the red paint around the bottom left has also stained it. The number of creases throughout the photograph make it particularly fragile and in danger of tearing if not handled carefully.

This photograph not only has red paint on the sides and on the image, but it also has a fragment of another photograph and black construction paper stuck to it. Toward the top of the fragment is a small piece of thick adhesive.

I used a micro spatula (a small, stainless steel spatula) to gently scrape crumbling adhesive residue, red paint, and old pieces of tape off the front and back of photographs and to separate the fragment image from the front of the photograph above. I also used a brush, a rubber cement eraser, and Absorene book and paper cleaner (an absorbent, putty like dry cleaner) to remove smaller amounts of residue and dust. When I removed old tape that was covering tears on the back of photographs I replaced it with document repair tape, which is acid free and safe to use on archival materials because it is removable and will not deteriorate like regular tape. Below are the same images after I cleaned them.

Cleaning these photographs was a long process, but very rewarding as the images are now stable and much easier to see, handle, and store. The cleaning has also prevented further damage from the acidic adhesives. Although there are still red markings and some adhesive residue on the images, I did as much work as I could to clean the photographs without potentially damaging them. In the future it could be possible for a specially trained Photograph Conservator to restore some of these photographs.

The finding aid for the Victor (Vic) Boff Collection, as well as finding aids to other processed collections, can be found on the Stark Center website. A portion of our finding aids, including this one, are also available online through the Texas Archival Resources Online (TARO). Researchers can contact the Stark Center by email at info@starkcenter.org or call (512) 471-4890 for access to archival collections.

Sources:

Bass, Clarence. “Clarence among Invited Guests at AOBS 25th Annual Reunion/Dinner.” Ripped. https://www.cbass.com/AOBS25Reunion.htm.

Bonomo, Joe. The Strongman: The Daredevil Exploits of The Mightiest Man in The Movies. New York: Bonomo Studios Inc., 1968.

Pearl, Bill, George and Tuesday Coates, and Richard Thornley, Jr. Knoedler, Trudi, ed. Legends of the Iron Game: Reflections on the History of Strength Training. 3 vols. Oregon: Bill Pearl Enterprises, Inc., 2010.

Riell, Howard. “Vic Boff: A Legend, Naturally.” Brooklyn Graphic Magazine, October 27, 1982.

Rosa, Dr. Ken “Leo.” “Farewell to Vic Boff.” Iron Game History 7, no. 4 (2003): 12-13. https://starkcenter.org/igh_article/igh0704c/.

Thomas, Al. “Vic Boff: The Old Game’s Best Friend: Face-to-Face—and by Proxy.” Iron Game History 7, no. 4 (2003): 1-11. https://starkcenter.org/igh/igh-v7/igh-v7n4/igh0704a.pdf.

Victor (Vic) Boff Collection, The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture & Sports, The University of Texas at Austin.

Remembering Igor Galanin 16 Dec 2024 4:02 PM (10 months ago)

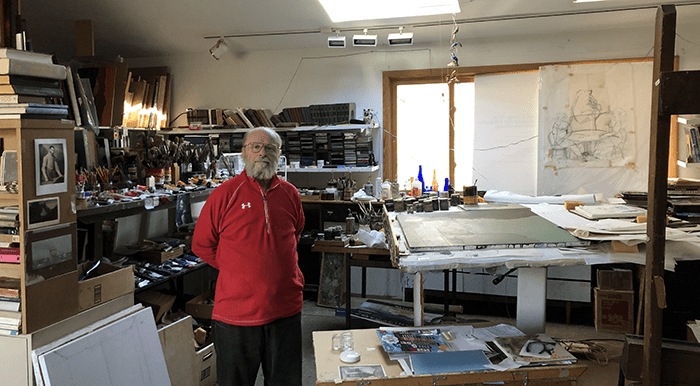

I recently learned that the artist Igor Galanin passed away this fall on Saturday, November 16. I was so sorry to hear of his passing and know that there are many who will miss him dearly. Although I was not part of the team that traveled to New York to collect or return the paintings Igor loaned to the Stark Center in 2022, his life and his art still had a significant impact on me and my work at the Stark Center. I like to picture Igor as I knew him, at 85 years old, still eagerly painting in his second-story studio in Millwood, New York while classical music or Russian opera fill the space with sound.

Local readers will shiver and recount their stories of survival if you ask them about the historically severe winter weather incident of February 2021—a tremendous freeze and storm that engulfed the state of Texas, causing disastrous power outages and over a billion dollars in damages. The Stark Center, like many other buildings on the University of Texas campus, suffered the storm, the freeze, and their effects. Our location in the North End Zone of DKR-Texas Memorial Football Stadium is directly below open-air concession areas where exposed pipes—i.e. water fountains, bathroom sinks, etc.—froze and burst in the extreme cold. The frozen pipes then began to thaw as temperatures rose above freezing for the first time in eight days. The water released in the thaw then found its way through the thick concrete floor and rained down on our lobby and exhibit spaces, flooding the Stark Center. Fortunately, no artifacts or resources were lost or harmed, but our beautiful floor was ultimately damaged beyond repair. If you’ve ever visited our space, you’ll know that our floor is a one-of-a-kind piece due to the custom air-brush application of different color stains that results in a nice, fluid burnt orange hue. The floor is also a singular entity, void of any seams, which meant that we couldn’t replace or repair damaged sections; we had to replace the entire floor in a massive construction project that required a full de-installation of our lobby and exhibit spaces. When the new floor was finally complete and the Stark Center was able to re-open its galleries to the public, we took advantage of the opportunities a restart provided us and looked to change up our lobby.

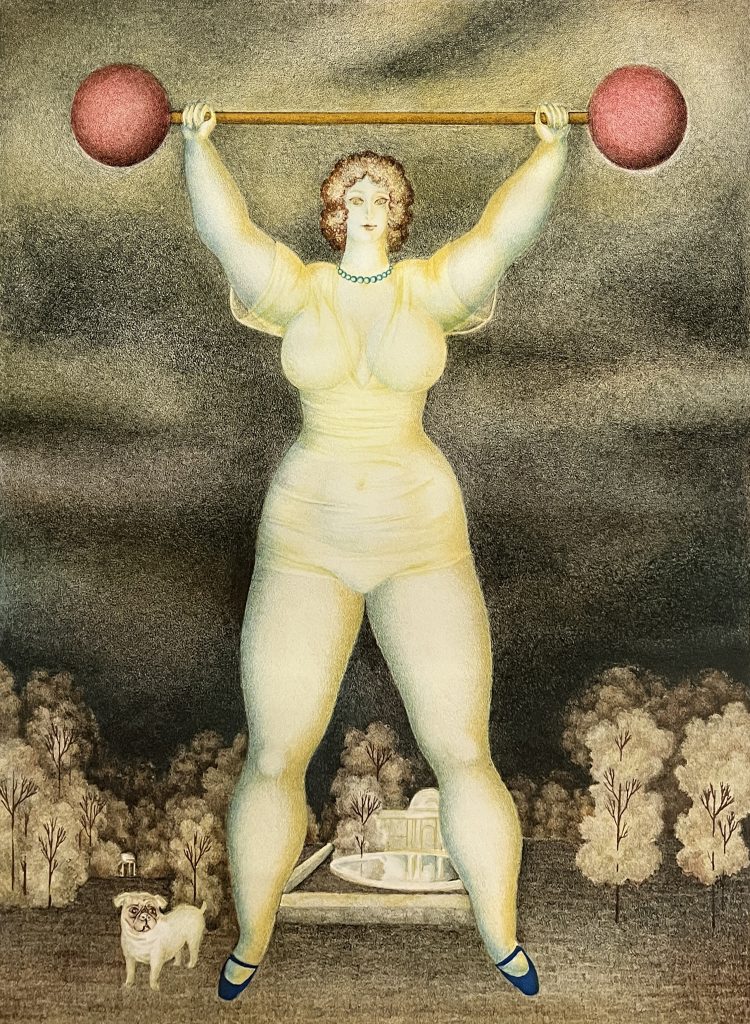

The curved back wall, centered on large, double doors vinyl-wrapped with a cover of the magazine Physical Culture, was previously populated with what had been called the “Wall of Honor.” It included large photo panels featuring significant figures in the history of physical culture—from Eugen Sandow and Katie Sandwina to Joe Weider and Jack Lalanne, John Davis and Tommy Kono to Boyd Epley and Kenneth Cooper. I decided to relocate this Wall of Honor to the main hallway of our galleries, the aorta through the heart of our exhibit space so to speak, and renamed it the “Hall of Honor.” This shift gave Stark Center Director Jan Todd and me a fresh blank space to work with. We didn’t have to brainstorm for a terribly long time. Jan had just purchased a painting from an online auction site which featured a woman, whose large and rounded figure dominated the foreground as she held a significant barbell overhead, seemingly with little effort. A small dog stands by the woman’s right foot and while the entirety of the piece seems to have a subdued color palette, the globe ends of the woman’s barbell are distinctive red, her necklace is remarkable for its bright green accents, and her small shoes are a bold shade of blue. The new piece was a novel addition to our already unique collections, and it delighted the entire Stark Center staff. Jan had spent time doing some online searches with the artist’s name, “Igor Galanin,” and found his website. Perusing the portfolio of work on his site, Jan saw more of this playful and imaginative style along with striking color choices and, amongst animals and other fanciful imagery, a significant number of paintings had women engaging in sport, athletics, or other physical activities. Jan sent me a link and we wondered how difficult it might be to contact Igor and if he would agree to loan us his female athlete paintings for an art show in the Stark Center lobby while we came up with an idea for a more permanent lobby installation.

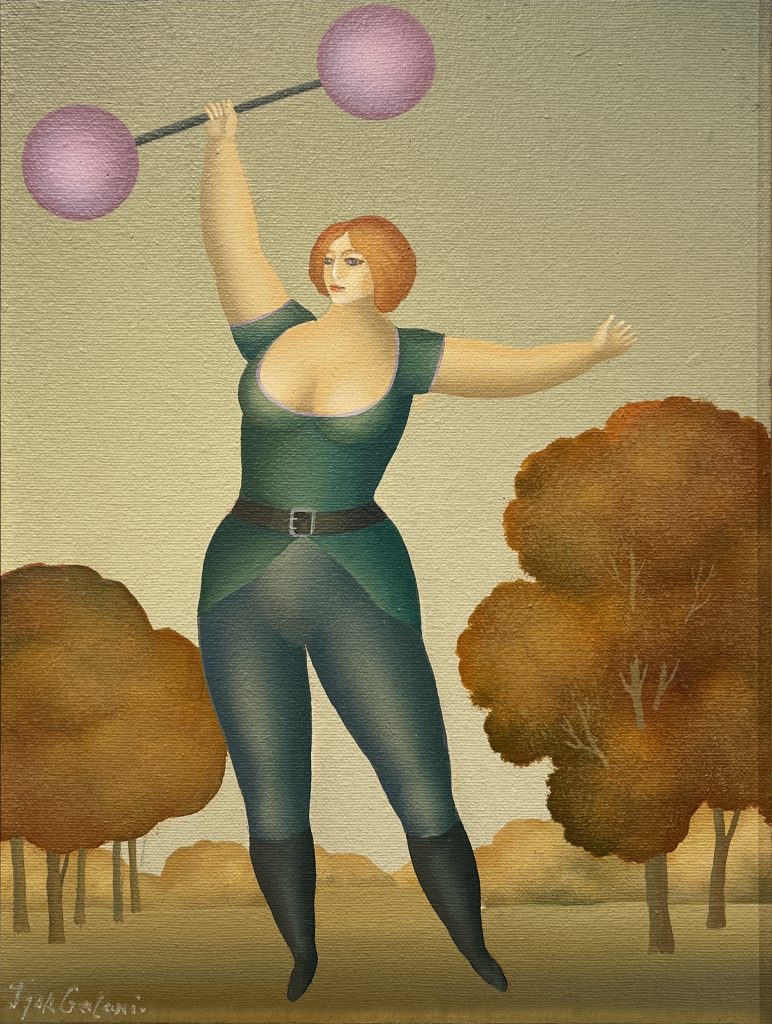

We learned that Igor Galanin was already an established artist in the Soviet Union when he, his wife, and two children immigrated to America in 1972. He had his first American show in 1974 in New York City and his breakthrough exhibition in 1975 at the Rose Art Museum in Boston. Galanin’s arrival in America coincided with the passage of Title IX in 1972. Over the next decade or so, magazines and television programs were filled with stories about the rise of women’s sport and the new generation of female athletes. It’s possible that this new world of strong, skillful women inspired Galanin to begin painting female athletes, a highly unusual subject for the world of art at the time. Throughout the 1980s, Galanin kept painting women athletes—tennis players, horsewomen, cyclists, skaters, boxers, and swimmers. In the 1990s, his focus seemed to pivot to women of the circus world.

Connecting with Igor was not difficult. He was a kind and charming man, still very much in love with his work, and he was delighted to loan us a significant number of paintings for display. Jan, Kim Beckwith, our assistant director, and Kim’s sister, Kathy Robinson, made the trip to Millwood to meet Igor and collect the paintings. They wrapped each one safely and in accordance with industry standards before loading them into a rented truck that Kim and Kathy then drove back to Austin. While there in his studio, Jan asked Igor about the women in his paintings. None were based on real people, he assured Jan (and his wife). They were women from his imagination, painted in vivid colors as a celebration of his ideal of athletic beauty. While in his studio, Igor proudly presented an original drawing to each of the women carefully wrapping his paintings. Each was of a mermaid. Before the team left, Igor, Natalia, and their daughter Masha invited Jan, Kim, and Kathy to have tea and cake while chatting about Texas and becoming fast friends.

For eight months Igor’s paintings adorned the Stark Center lobby. We titled the exhibit, “Igor Galanin’s Women of Strength and Skill.” The art show brought a fresh new aspect of physical culture to our museum. But more importantly to me, it brought a new world of color. It would probably be over-dramatic to compare the effect to Dorothy’s transition from her black-and-white home in Kansas to the technicolor land of Oz, but the burst of color, the size of the paintings, especially the later circus-themed pieces which were very large and the most brightly hued, seemed to pull people into our space from the elevators. The Galanin paintings seemed to be a draw, a welcome sign, an invitation to visitors to move, inspect, and explore.

I didn’t miss the lesson that Igor and his paintings taught me. When it was time to close the exhibit, we packed up the loaned paintings, then Kim and Kathy drove them back to Millwood, leaving Jan and me to begin working on our new grand vision of an orientation point for first-time visitors that would cover the full stretch of the curved, lobby wall. The result of that project is the new vinyl wrap on the double doors that presents (in gigantic text) the question, “What is the Stark Center?” And, of course, we try to answer that question with eight new text/photo panels along the curved wall, each of which highlight a different aspect of our large and ever-expanding collection. But it was distinctly Igor’s influence that inspired my choice to overlay all the images on these panels with eye-catching shades of Southwestern blue, red, and orange. It was important to me that the curved, lobby wall maintained the same vibrant, welcoming effect that Igor’s colorful world once brought to the Stark Center. In doing so, it would seem, that there’s a small piece of him still here with us today.

To learn more about Igor Galanin, his life and his work, please visit his website: igorgalanin.com.